The BBC’s sitcom/comedy drama, Detectorists, centred around two middle-aged metal detectorists and their hobby, is not noticeably ground-breaking, cutting-edge, politically savvy, conspicuous in its social realism, culturally diverse, sexually promiscuous, obscene, coarse, or expletive-laden in its language, nor vitriolic and in-your-face with political rancour. It is gentle, good-humoured, almost somnambulist in its tone and pacing, and with a touch of gentle eccentricity in ways we are familiar with where BBC sitcoms are concerned. Written, directed, and starring Mackenzie Crook (Andy), and also starring the acclaimed British actor, Toby Jones (Lance), Detectorists is also a very British object in ways that have been remarked upon by various critics, and in ways I will further explain in relation to folklore and my ideas of a ‘Folk TV’ – ideas which elsewhere have been described as ‘Wyrd’ TV or ‘Wyrd’ media (Rodgers, 2022).

In all of the reviews, criticisms, and other writings researched for this paper, Detectorists has been described as “deliberately understated” in its focus on “the mundane” activity of metal detecting, not afraid to “go small”, and its comedy seemingly “of another era” (Schwanebeck, 2019, p.100). It is “heart-warming…charming…”, offering a “comforting familiarity”, according to Adam Fleet of The Guardian (2019)”.

Similarly, but more interestingly, Neil Armstrong for BBC Culture, in an article on ‘Detectorists: Why a metal-detecting show became a global hit’ (19th December 2022), describes the programme as “low-stakes, cheerfully bucking every TV trend.”, and goes on to say, “In a world of expansive, expensive epics, it’s a priceless miniature.”.

This combination of comforting familiarity and global appeal offers a particularly interesting dynamic. Detectorists is enjoyed in various countries including Israel, France, Germany, India, and America. But its global appeal is something of a mystery to the show’s writer, director, and star Mackenzie Crook who offers a possible explanation stating, “It was always my idea to write an uncynical comedy about hobbyists for hobbyists – people with obsessions – and I guess those sorts of people are all over the world.” (BBC Culture, 2022).

Hobbyists from around the world have clearly played a part in sharing their love for the programme.

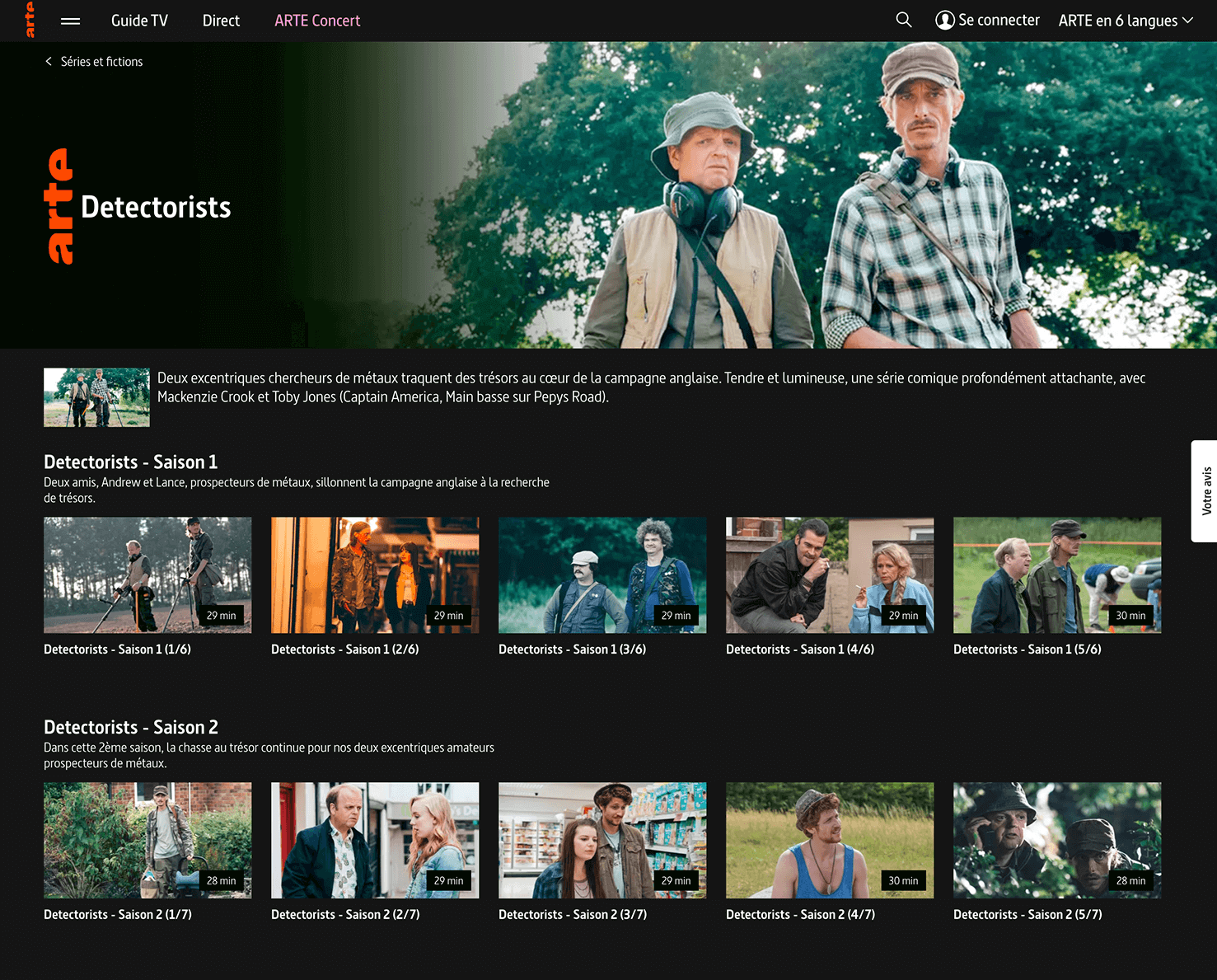

Coins Weekly, a German/British online magazine and “bridge to the international numismatic world” for “collectors, numismatic dealers and researchers” (with “readers in 170 countries” – I kid you not), recently ran a special article titled ‘Detectorists on German and French Television’ (Kampmann, January 21st 2021), enthusiastically describing the programme as “quirky” and “delightfully politically incorrect”, observing how encouraging it is to see the European broadcaster ARTE offering a subtitled British comedy to French and German audiences on metal detecting – “a popular sport in Britain that is enjoyed by all social classes.”.

Interestingly, this same article cites the Detectorists as an example of popular TV “sparking discussions on topics that were taboo before”; although it is fair to say their example of the collaboration of state archaeologists and private detectorists (“a taboo subject in many countries”) is probably not the example that most people would expect, but is perfectly in-keeping with the obsessive nature of the show it alludes to.

Detectorists, therefore, is both familiar, in a very local, British sense, and unusual in ways that I will argue are ‘wyrd’, but which, nevertheless, has seemingly universal appeal. It offers a sort of quaint, eccentric, appeal to global audiences who may not get all the specific cultural references, but who see it as soothing, quirky, and having “pastoral elements”, with the LA Times describing it as “almost Shakespearean”, comparing it to A Midsummer’s Night Dream (BBC Culture, 2022).

Its quaint, unassuming British eccentricity is an important factor, both to the sitcom itself, and where exported British TV is concerned. Eva Novrup Redvall, in her study of ‘Midsomer Murders in Copenhagen’ (2016) has examined how the ‘comfy crime’ British TV drama Midsomer Murders (ITV, 1997 -) has enjoyed international success for many years, and its appeal to Danish audiences in particular lies in “its quaint setting and leisurely pace which is comforting for viewers…”; also, its “cosy, comforting, charmingly eccentric criminality”. (Redvall, 2016, p.349). Clearly, the appeal of some British TV dramas abroad owes much to a ‘comfy’, gentle, eccentric, and quaint idea of Britain and British culture.

Detectorists can clearly be seen in much the same way, but there is also something else that makes it distinctively British. Therefore, whilst it showcases the BBC’s penchant for eccentricity and embarrassment, elements that are essential to its gentle and peculiarly British form of comedy, its eccentric moments potentially allude to something more ‘wyrd’ and different.

With regard to embarrassment, Frances Gray, in her essay, ‘Privacy, Embarrassment, and Social Power: British Sitcom’ (2005), (a title that seems prescient in describing some of the foibles raised in Detectorists), observes how the element and function of embarrassment in sitcoms reveals a variety of purposes and realities, not least social status and power dynamics.

This is arguably the case in Detectorists. Schwanebeck, in his study of the programme, ‘A Field That Is Forever England: Nostalgic Revisionism in Detectorists (2014-2017)’ (2019), observes how one of the themes of the show could be described as “middle-aged masculinity in crisis” (2019, p.100), with humour designed to gently expose inadequacies and awkward failings, (the ‘Finds’ Table, drink can ring pulls instead of treasure, etc.), misunderstandings, embarrassing, obsessive hobbyist behaviour, and “the puncturing intrusion of reality that floors lofty aspirations”. (Schwanebeck, 2019, p.102).

As Gray states, “Embarrassment does not mean sympathy with a character’s actions – often the reverse – but it does involve the sense of privacy violated… it leaves us with a sense of our own, real, damage” (Gray, 2005, p.147), and possibly a sense of our own peculiar, and eccentric obsessions/behaviours. This is an element, therefore, which audiences can relate to and share with the characters.

Similarly, Schwanebeck, in his study of Detectorists, describes how the show “whilst never resorting to cruelty, constantly mines humour from belittlement” (2019, p.102), either through themes of domestic/professional shortcomings, or visually, through the cinematography of panoramic aerial camera shots which “draw attention to man’s relative insignificance” in the landscape, and “to the over‐whelming force of history” (2019, p.103).

Whilst the function of embarrassment can be seen as just one traditional expectation and convention of British sitcoms, the feature of eccentricity is an element which is exploited in interesting and ‘Wyrd’ ways in Detectorists, and it is here that i will argue for the show exhibiting a sense of ‘Folk Television’, or what Rodgers, in her essay and conference paper, ‘Et in Arcadia Ego: The Very British Landscape of Folk Horror’, calls Wyrd TV or Wyrd media (2022).

Fig. 2: Conference presentation slide from Diane A. Rodgers’ presentation titled “Wyrd TV: Folklore, folk horror, and British 1970s Television”

My reasoning for placing emphasis on the gentle nature of Detectorists is, in part, connected to my observations of what I perceive as ‘Folk’ Television, which offers a contrast to British Folk Horror. Recent Folk Television, I argue, is more gentle and more whimsical in the ways it taps into actual or imagined folklore. Whilst sharing certain important elements with British Folk Horror, such as a focus on landscapes and references to folklore, these elements in Folk Television are often used differently, and function in ways that are observable across various television examples, most notably in the BBC’s Detectorists. Lacking the gore-ish horror, and the depictions of real harm of Folk Horror, Folk Television can often solicit a haunting eeriness, but mostly deals with ideas and content that suggest things being “uncannily out of time and place” (Rodgers, 2019).

That Folk Television functions in different ways to Folk Horror is largely due to its traditional or perceived audience. Whilst Rodgers describes ‘Wyrd TV’ as a fairly recent phenomena, early prototype examples of Folk Television can be traced to a strain of 1970s children’s TV shows, along with a folk revival in popular British and American music. This said, Rodgers does cite British TV examples of the period such as Quatermass (ITV, 1979), and Children of the Stones, (ITV, 1977), to name just a few, as important examples.

Detectorists, therefore, whilst made for an older audience, can still be understood in terms of a Folk Television, and also in relation to shared elements from Folk Horror, such as an “The importance of Landscape” (Scovell, 2019), and in various references to folklore and superstition. From its opening theme and it use of incidental folk music, written and played by Folk musician and actor Johnny Flynn, the tone of Detectorists is very much in tune with a folk culture.

In terms of folklore, Detectorists provides an interesting dichotomy. On the one hand, both Andy and Lance fully embrace scientific means of discovery – the use of modern technology in the form of metal detectors. Further, they try to rationalise their hobby via membership of an official (Danebury) Metal Detecting Club, and through proffered nuggets of historical details and information. Andy even becomes a qualified Archaeologist. However, their hobby is also a calling of sorts, and works on a more spiritual, instinctive, ‘Wyrd’, almost superstitious level. We can see these folkloric and superstitious interventions throughout the series. A notable example occurs in the Series 3, Episode 1 ending when Andy finds a medieval hawking whistle. Blowing the whistle, Andy unknowingly summons or ‘unearths’ the past, a haunted landscape and a haunting in the manifestation of a Roman family burial. The tone and vision are completed by the accompanying music – a folk song called Magpie by the folk band The Unthanks. In fact, Magpies, or at least one particular jewel-snatching Magpie, is another, recurring folkloric intervention in the series.

Cormac Pentecost, the editor of a Detectorists fanzine, Waiting for You, remarks on how some episodes have “eerie, ghost-story elements”; and Mackenzie Crook describes how his childhood fascination with the supernatural, as well as his work on that other candidate for Folk Television, Worzel Gummidge (BBC, 2019), has bled into his work on Detectorists – “it was an opportunity to explore those mystical elements and themes in a more obvious way” (BBC Culture, 2022).

Another important shared element of both Folk Television and British Folk Horror is a preoccupation with or focus on Landscape. The manifestation of a haunted landscape at the ending of Season 3, Episode 1, as alluded to already, is just one notable example. As Rodgers (2022), Gatiss (2010), Scovell (2019), and others point out, British Folk horror is “often associated especially with landscape and themes of ‘unearthing’ which help to characterise British folk horror with its own peculiarly national sense of eeriness” (Rodgers, 2022). In Detectorists, both Andy and Lance pride themselves on being able to read the landscape, and of course, their hobby is ‘unearthing’ the landscape. Rodgers, citing Macfarlane, draws attention to the function and symbolism of ‘unearthing’. In British Folk Horror, this “digging down to reveal the hidden content of the under-earth” is an important eerie trope, often involving the releasing of a “repressed pagan past”, and certain types of folkloric beliefs (Rodgers, 2022). It is a convention we see throughout many examples – A Field in England (Wheatley, 2013), Blood on Satan’s Claw (Haggard, 1971), M R James and BBC Ghost Story for Christmas series of the 1970s, et al.

In her recent review of the book Landscapes of Detectorists (Keighren & Norcup eds., 2021), for CST, Christine Geraghty also draws attention to the importance of landscape in Detectorists. Geraghty points out how the authors were “fans of the programme but are also academics in cultural and historical geography, interested in the rural environment, the English landscape and the relationship between memory and place, objects and knowledge.”. Landscapes, and Folklore then, are significant to describing a Folk Television, and Detectorists highlight these potentially ‘Wyrd’ elements and themes in ways that have generated both local and global appeal.

Fig. 4: “Landscapes of detectorists” has been the theme of the RGS+IBG Annual International Conference, which took place from August 28th to 31st, 2018.

In one notable ending scene, from Episode 6 of Season 2, we can see all the strands of Folk, Folklore, superstition, science, and landscapes come together. Convinced he can hear the haunting sounds of horses, Lance takes one more sweep with his metal detector, and with the prompt of a signal he begins to finally unearth his longed-for treasure in the form of Saxon gold. Here, through the process of ‘unearthing’, Lance and Andy do not so much unleash a devilish repressed horror, but the hopes and dreams of the present informed, in equal part, by the treasures and detritus of the past. Detectorists is a programme that has struck (Folk) television gold.

Kenneth A Longden is a Lecturer in Television, Film and Media, University of Salford, and a Fellow HEA.