“It’s impossible to watch HBO’s Chernobyl without thinking of Donald Trump,” tweeted the author Stephen King in May 2019, simultaneously offering a backhanded compliment to a television miniseries that was fast becoming a critical sensation and a withering takedown of Trump’s presidential capacities. “Like those in charge of the doomed Russian reactor, he’s a man of mediocre intelligence in charge of great power – economic, global – that he does not understand.”

That was four years ago. As Trump flailed against a seemingly endless barrage of accusations of corruption, scandal and incompetence, Chernobyl and its creator Craig Mazin enjoyed glowing reviews and popular acclaim. By early June 2019, this dramatic account of the Soviet nuclear powerplant’s explosion in 1986 and aftermath had been voted the highest rated television show of all time by Internet Movie Database users (9.7 out of 10) and was widely touted to win big during the awards season (which indeed it did).

Much water has passed under the bridge since 2019: in politics, in science, in global relations, in popular culture. At the time of writing, America’s 45th president is now America’s first president to be criminally indicted. Mazin is enjoying, if anything, even more plaudits for his latest character-driven, biological-disaster-themed drama, The Last of Us. But as a series that, I argued in my contribution to Karen McNally’s edited volume American Television in a Television Presidency (Wayne State University Press, 2022), mediated so many of the political and cultural exigencies bedeviling the US circa 2019, Chernobyl still strikes me as an impactful watch, replete with timeliness and currency and well worth revisiting.

In 2019, discussion of Chernobyl often focused on it as a political allegory. Some commentators (like King) saw a coruscating attack on the Trump-era, from governmental mismanagement and anti-intellectualism to, as one New York Times critic put it, “what happens to societies corrupted by the institutionalization of lies and the concomitant destruction of trust.” That said, there were others that argued Chernobyl simply represented the failures of Soviet governance and, by extension, asserted the US’s comparative stability. Apparently, Russian state news outlets reported on the series as an example of anti-Russian “American propaganda” and announced plans for a new Russian Chernobyl series, which declared the disaster to have been instigated by nefarious CIA operatives.

Should you happen to view either the Trump or the 1980s Soviet administrations as incompetent, deceitful, disorganized or out-of-touch with ordinary people, Chernobyl contains much grist for your mill. At the heart of the miniseries is a straightforward tale of plucky underdogs standing up to sinister elites. There are four key characters – the scientists Valery Legasov (Jared Harris) and Ulyana Khomyuk (Emily Watson), a Communist Party apparatchik Boris Shcherbina (Stellan Skarsgård) and Lyudmilla Ignatenko (Jessie Buckley), a woman whose life is forever impacted by the disaster and its fallout.

As the narrative progresses, Legasov and Khomyuk turn from competent, cautious scientists into heroic whistleblowers, ready and willing to challenge the Soviet power structure. Shcherbina begins the series as a committed Party man but concludes it as cynical toward the state as his scientist compatriots. Ignatenko’s story – based on a real interview published in Svetlana Alexievich’s renowned collection Chernobyl Prayer – also becomes a channel through which to broadly reflect on the disaster’s impact on ordinary people. Presented at once as a victim (of the disaster, of the lies told to the public) and brave survivor, she suffers the loss of her husband, her unborn child and her health, while ultimately finding a new life in the years to follow.

Chernobyl’s power is, however, in how this material is delivered. Formally and stylistically, the miniseries is indebted to horror and suspense, presenting a rollcall of dark corridors, high angles, surveillance shots, eerie sounds and Steadicam.

There are some striking visual parallels, such as the leisurely tracking shots over unsullied woodland that appear toward the end of Episode 1 and Episode 5, drawing thematic connections between the invisible destructiveness of radiation and the equally “invisible” destruction wrought by lies and deception. Of particular note is Hildur Guðnadóttir’s haunting score, which not only invests scene after scene with atmospheric tension but was thematically on point, as she apparently constructed it from recordings she made at power plants.

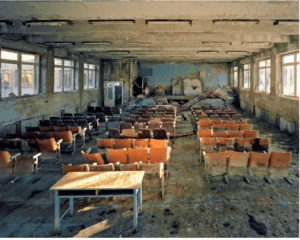

Mazin and director Johan Renck appear to have been very familiar with the visual culture of Chernobyl. Many scenes and sequences evoke previous images associated with the disaster and its aftermath. Mazin’s screenplay for Episode 2 requests the camera “silently drift” through the abandoned Ukrainian city of Pripyat and linger on empty school classrooms, apartments, a “pair of old shoes [lying] next to an unmade bed” and the iconic, never-used Ferris Wheel “[creaking] gently in the breeze.”

Such imagery has been incorporated in all manner of representations since 1986, from Igor Kostin’s early efforts to photograph the clean-up operation to the “late photography” of Robert Polidori and Rüdiger Lubricht. By envisioning an unseeable, invisible menace, images of Chernobyl have long tried, as Melanie Arndt observes, “to make the empire of standstill and void visible.”

I found myself recalling these photographs – and, indeed, scenes from Chernobyl – when strikingly similar images began appearing as the coronavirus pandemic swept the world and lockdowns brought many countries to a halt. In these contemporary shots of abandoned buildings, empty streets and clean-up operations were quiet counterpoints to the bluster of figures like Trump, whose “rambling press conferences”, as McNally describes them, “aimed at challenging the data on the United States’ spiralling case numbers.” And, with anti-scientific diatribes, untruths and political manoeuvrings a frequent talking point throughout the pandemic – discussed against the backdrop of an invisible, deadly threat – there was a grim serendipity in revisiting Chernobyl and its parallel subject matter.

Of course, Chernobyl was written, produced and broadcast some time before the phrase “COVID-19” entered common parlance. It wasn’t about the pandemic just as, when Mazin started work on the drama in 2014, it wasn’t necessarily about Donald Trump. These interpretations gathered around the series through its development and afterlife. But there is something about this grey, grim, grotesque and undoubtedly gripping drama that demands (when I watch it at least) a reaching for today’s newspapers.

According to reports of 2019, the release of Chernobyl instigated a boom in “dark tourism” to the powerplant and nearby abandoned Ukrainian city of Pripyat. The very idea of such trips now sounds quaint to say the least. War, as the saying goes, is not a metaphor. And Chernobyl is just a television series.

I would return, however, to Stephen King’s 2019 comment about it being difficult to watch Chernobyl without thinking of Donald Trump. I’d add that, in 2023, it’s difficult to watch it without thinking about so much that’s happened in the intervening years. In its visual power and thematic potency, Chernobyl offers, to borrow Gary Edgerton’s term, a “usable past,” a provocation to reflect on history, critique the present and anticipate the future, whatever that might bring.

Oliver Gruner is a Senior Lecturer in Visual Culture at the University of Portsmouth. His research has a particular focus on visual histories and representations of the 1960s and 1970s. He is the author of Screening the Sixties: Hollywood Cinema and the Politics of Memory (Palgrave, 2016), co-editor (with Peter Krämer) of Grease Is the Word: Exploring a Cultural Phenomenon (Anthem, 2019) and has published articles on sixties representation in film, television and comics in various journals and edited collections. He is currently writing a history of Hollywood screenwriters of the 1960s and 1970s, a project for which he received a Harry Ransom Fellowship from the University of Texas, Austin.

References

Arndt, M. “Memories, Commemorations, and Representations of Chernobyl: Introduction.” Anthropology of East Europe Review 30, no. 1 (Spring 2012): 1-12.

Edgerton, G.R. (2001). “Introduction: Television as Historian: A Different Kind of History Altogether.” In Television Histories: Shaping Collective Memory in the Media Age, edited by Edgerton and Rollins, P.C. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky.

Mazin, C. (September 21, 2018). Episode 2- Please Remain Calm, https://johnaugust.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Chernobyl_Episode-2Please-Remain-Calm.pdf

McNally, K (ed.). (2022). American Television During a Television Presidency. Wayne State University Press.

Rainsford, S. (June 7, 2019). “What did Russia think of HBO’s Chernobyl.” BBC News, https://bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-48559289

Shaw Roberts, M. (July 22, 2019). “Chernobyl Soundtrack: Who Composed the Haunting Music for the HBO Miniseries?” Classic fm, https://classicfm.com/discover-music/chernobyl-soundtrack-composer-hildur-gunadottir/

Spangler, T. (June 5, 2019). “HBO’s Chernobyl Is Now the Top-Rated TV Show on IMDb.” Variety, https://variety.com/2019/digital/news/chernobyl-top-rated-tv-show-all-time-1203233833/

Stephens, B. (June 20, 2019. “What Chernobyl Teaches About Trump.” New York Times, https://nytimes.com/2019/06/20/opinion/chernobyl-hbo-lies-trump.html