Why is there so little TV scholarship about TV and sports?

—John Ellis

John Ellis posed this simple yet salient question in his think piece for this online forum back on 21 May 2021. Given the outsize role that sports programming has played on TV around the world since the medium’s inception, it is indeed surprising that this subject has drawn such little interest from most television scholars over the years. Ellis ended his commentary by ruminating that ‘sport and TV have an intricately entangled history which continues into the present. What has really puzzled me for a long time is why TV scholarship hasn’t noticed it?’

There are undoubtedly no easy answers to this question. Sports is second only to news as the programming genre that has contributed the most to the growing local, regional, national, international, and global awareness of TV audiences all around the world. Events such as the quadrennial FIFA (International Federation of International Football) World Cup and the annual NFL (National Football League) Super Bowl offer ample opportunities to observe and analyse the glocal (global-local) nexus within and across cultures. It is safe to say from the outset that the significance of TV sports goes far beyond the literal playing of these games and the final scores.

Maybe another reason why sports on television is often overlooked as a topic by TV scholars is because it is best categorised as everyday programming as opposed to being considered prestige TV. In America, specifically, a surprising 60% of all television shows were sports oriented at the dawn of TVI/the Network Era (1948-1975). This percentage leveled off to approximately 20-to-25% during the 1950s where it has consistently remained within this narrow distribution ever since.

Another factor to consider is that play is universal among humans, but sports are specific to their sociopolitical and cultural contexts. As an example, the most popular US sports owe their greatest debts to attitudes, traditions, and games originating in England. During colonial times, sports developed differently in the American north and south. In the towns and cities of New England, sports were largely considered a waste of time, unwholesome, even ungodly. (Is it too much of a stretch to propose that unscholarly has replaced ungodly in our more secular times?) By contrast, horse racing, bare-knuckle boxing, and animal blood sports such as cock fighting—accompanied by much drinking and gambling—flourished in the more rural south.

The north may have won the American civil war, but the nation’s sports culture evolved predominantly from the landed white gentry of the south who had the status, wealth, and leisure time to advance the ‘sport of kings’ (horse racing), the ‘manly art’ and ‘sweet science’ (boxing), and even the English children’s game of ‘base ball,’ which was reshaped in the half-century before the civil war (1861-1865) to better fit the American experience. Southerners at the time thought of the New England Congregationalists (Puritans) and their like-minded northern brethren as ‘spoilsports.’

This admittedly condensed and oversimplified historical overview is intended to nevertheless suggest that Anglo-American culture has long been deeply conflicted about the inherent value of sports: they are fun but childish and mostly guilty pleasures. From a scholarly perspective, it is important to always keep in mind that the birth and emergence of nearly every local, regional, and national sports cultures long predate television or even radio.

Most populations moreover limit sports to those liminal spaces and times when people are seeking to escape the quotidian drudgery of their workaday lives. It is unsurprising, then, that sports on television are still reflexively regarded as nonessential pastimes that may prove culturally significant on only rare occasions, such as the nonstop global TV coverage of the 1972 Munich Olympics when eight Black September terrorists took hostage and eventually massacred the eleven-man Israeli team. For the most part, though, TV sports are considered frivolous entertainments that are easily devalued as sites of serious study.

Jim McKay anchored the Munich Olympic hostage crisis for 14 straight hours averaging an estimated 100 million worldwide viewers including 45 million in the US alone (ABC, 5-6 September 1972, 1:52)

Still, sports on television do offer up countless industrial and economic research possibilities to explore on the national, multinational, and transnational levels. For instance, the sports market in America is the largest in the world at a valuation of $83.1 billion in 2023 of which television rights alone account for $21.5 billion or 25.9% of that business. The 75-year relationship among TV, sports, and advertising (with the more recent addition of subscription revenues) underpins and drives most of the decisions made about nearly every aspect of professional sports in the United States.

Similarly, sports worldwide have undeniably affected business trends throughout the global television industry; spurred technological innovation; and surpassed even news as the bread-and-butter programming staple of live TV. Dozens of examples abound of television influencing rule changes in sports (for instance, shootouts in football after extra time and in hockey after overtime; the move from match play to stroke play in golf); scheduling modifications; and the laser focus on personalities in sports coverage replacing a primary emphasis on strategies and tactics, which was more the norm during the 20th century.

In terms of technology and style, the TV screen in all its various shapes and sizes from home theaters to smartphones is now understood to be the new sports arena as stadiums are built today to enhance the television viewing experience above all other considerations. Sports have always been a principal driver in the development of technical innovations dating back to the earliest experimental sports telecasts in Germany, the UK, and the US during the 1930s.

Since then, the litany of television breakthroughs designed to improve sports programming, which in turn benefitted the medium as a whole, include the transition from black-and-white to color; the creation of increasingly smaller and higher quality camera, lighting, and editing equipment; cable-and-satellites; slow motion, instant replay, and multiple camera angles available on a single action; analog to digital; virtual reality, esports, metagaming, and many more technological innovations arriving one after the other on an almost yearly basis over the last half-century.

The rapt engagement with individual sports by audiences all around the world has also resulted in them being codified into specific subgenres with their own rules, settings, dramatic structures, character types, accompanying audio and video aesthetics and styles, and sociocultural themes and significance. Each TV sport therefore is a rich though largely unexplored focal point of interest on which critical-cultural analyses could be conducted that are likely to reveal a great deal about the intra-, inter-, cross-, and multicultural meanings that are dynamically at play in these subgenres.

Finally, TV sports scholarship may also be underdeveloped because of the widespread belief that sports for the most part are heavily gendered male, politically conservative, and culturally reactionary. No doubt there is some truth to this broad generalisation, although the ideological terrains of individual sports cultures throughout the world regularly prove to be far more complex and nuanced upon closer inspection than this commonly held stereotype suggests.

Sports on television frequently prove to be as socio-politically and culturally resonant as any other live, reality based or scripted programming genre, and sometimes more so. Up until now, TV sports has been a too often neglected topical area that has remained hidden in plain. A fresh scholarly current is just starting to gain momentum, however. One recent example is Sports TV by Victoria E. Johnson in which she hypothesises that ‘sports, as seen on TV in all of its iterations, is the central cultural forum for working through questions of community ideals, struggles over national and regional mythologies, and questions of representative citizenship’ (i). More theorising and TV sports scholarship of substance appears likely to follow in the future.

Let me conclude by offering some preliminary observations about a recent incident that speaks to the potential of sports on television as a scholarly subject. The biggest US sports story to emerge so far in 2023 is the near-death injury sustained by Buffalo Bills safety, Damar Hamlin, during the January 2nd prime-time Monday Night Football telecast on ESPN, ESPN2, and ABC before a combined audience of 23.8 million viewers. This highly anticipated game involving two divisional leaders—Hamlin’s Bills and the home team Cincinnati Bengals—began a few minutes past 8:15 p.m. ET before an additional 65,535 expectant fans attending live at Paycor Stadium.

With 5:58 left in the first quarter at 8:55 p.m. ET and the Bengals leading the Bills 7 to 3, the 6’ 200 lbs. 24-year-old Damar Hamlin made what looked to be a routine tackle on the 6’4” 218 lbs. 23-year-old Bengal wide receiver, Tee Higgins. Higgins’ right shoulder apparently hit Hamlin’s chest as the safety wrapped his arms around the pass catcher to drag him to the ground. Hamlin popped right up after the tackle, seemingly adjusted his face mask, and then immediately fell backwards motionless in cardiac arrest having suffered commotio cordis.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=yzbT9oG54OY

Damar Hamlin’s injury on Monday Night Football (ESPN, 2 January 2023, 1:19)

NFL sponsored paramedics who are required to attend every league game next ran onto the field where they administered nine minutes of CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) and oxygen to Hamlin, finally restarting his absent heartbeat. Foregrounding how TV routinely covers the handful of serious injuries that occur weekly in NFL games reveals a great deal about how the networks in partnership with the league do what they can to mitigate awareness of the sport’s ever-present violent aftereffects.

In the case of Damar Hamlin, the camera predictably pulled away from him on the playing field to a wide shot as the feed quickly shifted perspective from Hamlin’s catastrophic injury to an innocuous cluster of four successive adverts. The brute realities of the game were thus kept at bay from viewers as an unconscious Hamlin was removed from field in an ambulance and rushed in critical condition to the University of Cincinnati Medical Center out of camera view.

Fig. 1: Buffalo Bills star quarterback, Josh Allen, is shown in an unguarded moment watching his teammate, Damar Hamlin, being given CPR during the Monday Night Football telecast

Thankfully Damar Hamlin survived but no one was sure what his fate would be during the telecast. Play-by-play announcer, Joe Buck, relayed on air ‘four separate times in a span of 45 minutes . . . that the game would resume’ following the instructions he received from his ESPN colleague, John Parry, who was in direct communication with league officials in the NFL’s command center in New York City (Van Natta). Discussing next steps amongst themselves on the field, the Bengals and Bills coaches and players decided to return to their respective locker rooms, essentially taking the initiative from the bottom up to call the game by this collective action.

The life-and-death nature of Hamlin’s injury was an unexpected, shocking, and unwanted plot twist in the Monday Night Football script that evening. It moreover shines a bright light on the degree of cognizant dissonance that is required by the NFL, the television networks, the coaches, players, and other team employees; and most pointedly, the tens of millions of fans who en masse enjoy American football from the August preseason games through the Super Bowl in February year after year.

NFL central officially suspended the game at 10:01 p.m. ET or ‘66 minutes after Hamlin’s collapse’ and more than 30 minutes after the teams had left the field (Van Natta). By that point in the telecast, it was a forgone conclusion to the coaches and players, the on-air talent and viewers, as well as the remaining fans in the stands at Paycor Stadium that no more football would be played that night. The liminal spell of the game had been irrevocably broken that evening by the tough, gladiatorial, and unforgiving reality of the sport—but Americans do love it.

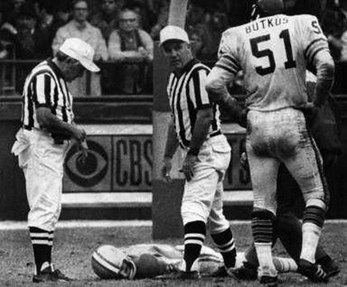

Fig. 2: Chuck Hughes, a 28-year-old wide receiver for the Detroit Lions collapsed and died on the field during the 4th quarter of the 24 October 1971 game against the Chicago Bears. Detroit team doctors tried to revive Hughes on the sidelines as CBS completed the telecast.

In 2022, for instance, 48 of the top 50 most-watched television programs in the United States were football games. When the Los Angeles Rams beat the Cincinnati Bengals 23-20 on 13 February 2022 in Super Bowl LVI, 113.7 million viewers (99.66 million on broadcast/cable-and-satellite; and 14.07 million through streaming) watched it in the United States alone. Another research question worth asking is how and why American football still hangs on in 2023 as the final vestige of a national monoculture.

The medieval roots of American football date back to English mob football, which in the intervening centuries evolved into rugby, football/fútbol/soccer, and US football. The important point in this historical reference is that each evolutionary branch that grew out of mob football reflects the national or transnational contexts that embraced and nurtured it. Football/fútbol/soccer is now the most popular sport on earth boasting more than 2 billion fans or approximately 25% of the world’s population. American football does have a multinational presence, but its most concentrated and fervent fan base resides in the United States.

The best historical-critical delineation into ‘why Americans watch . . . football . . . and what they see when they do’ was written nearly two decades ago by Michael Mandelbaum when he christened the sport the ‘spectacle of violence’ (iii, 119-198). Much has transpired in the country and American football since the initial publication of Mandelbaum’s The Meaning of Sports, not the least being the continuing propagation of US football throughout nearly every demographic group within the society and culture.

Take for example an 8 January 2023 opinion piece originally titled, ‘Damar Hamlin and the Beautiful Terror of Loving Football,’ by New York Times reporter and political pundit, Jane Coaston, who mused about her love/hate relationship with American football: ‘I have been a football fan for practically my entire life. I’ve watched hundreds, maybe thousands of college and NFL games, and I will watch football this weekend. My decision to do so is almost less a decision than a reflex. It is Sunday. I am me.’ Coaston heartfelt admission speaks for tens of millions of football fans in the United States—women as well as men. The latest survey data on NFL fandom is 53% male/47% female.

Suffice it to say that conducting a deep scholarly dive into why American football is the last gasp of a dying American monoculture in our diverse, segmented, and multicultural era is a research project worth pursuing. In fact, plumbing the cracks and fissures between the rhetoric and reality of any glocal sports culture and its relationship to television is likely to reveal much about the people who support, promote, and follow that mediated pastime. ‘The question of sport’ is timely as well as full of promise and opportunity (Ellis). Much more scholarly work needs to be done by TV scholars analysing sports on television.

Gary R. Edgerton is Professor of Creative Media and Entertainment at Butler University. He has published twelve books and more than ninety essays on a variety of television, film and culture topics in a wide assortment of scholarly journals, anthologies, and encyclopedias. His latest book is Mad Men: TV Milestones Series (Wayne State University Press, 2023). He also coedits the Journal of Popular Film and Television.

References

Coaston J (2023) This Sport Has Devastated the Lives of Players. What Do Fans Owe Them? New York Times, 8 January. Available at: https://nytimes.com/2023/01/08/opinion/damar-hamlin-football.html.

Ellis J (2021) The Question of Sport. CST Online, 21 May. Available at: https:///the-question-of-sport-by-john-ellis/.

Johnson V (2021) Sports TV. New York and London: Routledge.

Mandelbaum M (2004) The Meaning of Sports. New York: PublicAffairs.

Van Natta, Jr D (2023) Ground-up decision: How Bills, Bengals led the way after Damar Hamlin Collapsed. ESPN, 9 January. Available at: https://espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/35393227/how-bills-bengals-led-way-damar-hamlin-collapsed.