Why is there so little TV scholarship about TV and sport? Compared to the reams about Netflix, there’s hardly a decent book to be found anywhere, and nothing it seems after Garry Whannel’s Fields in vision: Television sport and cultural transformation of 2005, and Toby Miller, Geoffrey A. Lawrence, Jim McKay, and David Rowe’s Globalization and sport: Playing the world from 2000. Yet sport on TV has been central to the TV economy, driving technological and business innovations. Sport is perhaps even more of a linchpin of live TV than news.

Sport suited early TV technologies. It provided the first TV broadcasters with an ideal source of familiar events which had to be shown live and had a reassuringly long duration (cricket was perhaps a little too long even then). Sport had power in TV as a result: the first Ampex videotape recorder that the BBC acquired in 1958 was commandeered immediately by the sports department. Sport coverage has been a technical pioneer ever since, even down to early uses of drones, podcasts, narrowcasts etc. Sport – and particularly football – drove the development of subscription TV in most European markets, becoming the foundation of Sky’s operation. More recently, competitive bidding between subscription services has brought untold wealth to elite clubs and to their players. Then there is the whole sorry saga of on-pitch advertising, sponsorship, tobacco advertising etc, summed up by those strange stickers that appear behind managers in post-match interviews. And there are the constant themes (unexamined until comparatively recently) of gender and race, nationalism and localism, age and disability which run through the whole fabric of TV sport.

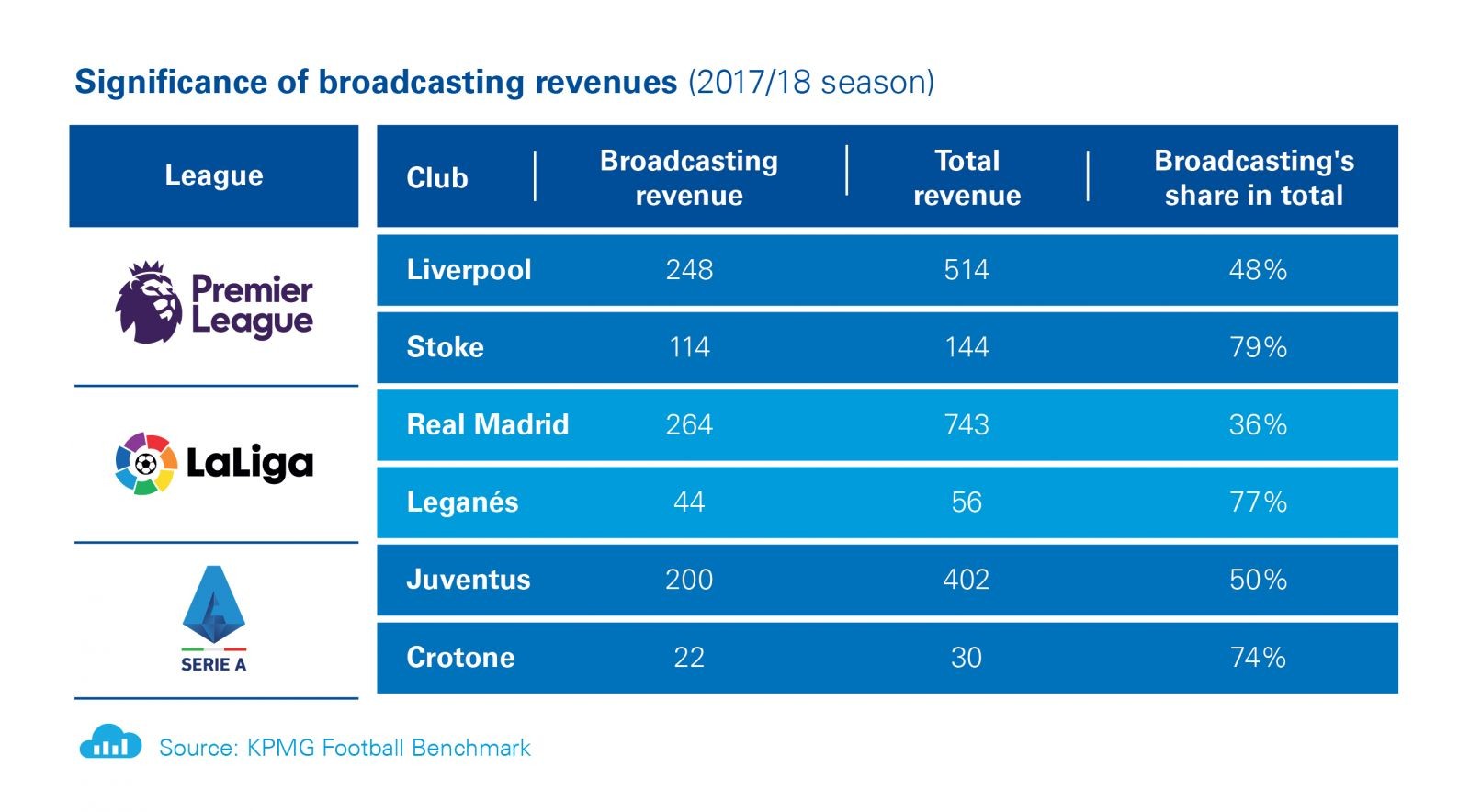

Fig. 1: Broadcasting revenue of selected UK, Italian, and Spanish football clubs. Source: KPMG

You would think that there is a compelling narrative here and plenty to research and teach. But maybe I’m typical of TV scholars in my general disinterest in competitive sports on a personal level. I’ve never been able to say “we” and “us” about a football team and so I’ve missed out on the quasi-masonic workplace networking that coheres around football talk. It seems that most TV scholars tend to like drama or comedy and so talk and write about that. But it’s never a good idea for an academic discipline to follow only the tastes of its proponents. There has to be a wider analysis of how the system works, where power lies and how that power intersects with wider organisations of social power. This kind of perspective should inform the areas of specialism.

Sport comes with its own power problematic, of course, because of male predominance, especially in TV coverage (tennis, one of the original TV sports, is largely an exception… except when it comes to the prize money). So you’d think that, given the recent startling discovery that women also do sports like football, there would be a flicker of research interest out there.

Two recent events have demonstrated the continuing importance of sport in TV culture. The abortive attempt by an elite group of clubs to create a European superleague was the logical culmination of the influence of TV on what the fans call “the beautiful game”. As Whannell pointed out ages ago, TV remade sport in its own image, creating a scheduled calendar of events with their long narratives of victory and defeat, cup winners and even cup winners’ cups. So, this was to be the cup winners’ cup winners’ cup with no-one else allowed in. Had no-one gone to a story consultant who would instantly have pointed out “where’s the jeopardy?”. The current set-up means that every club has the theoretical possibility of getting into the elite, and every elite club the more real possibility of relegation if they hit a losing streak.

The recent scheme for a self-perpetuating league of super-clubs was built on the model of how US sport (particularly American football) has evolved as a result of TV finance in the rather different market conditions of the US. An elite of US owners have recently moved into UK football and they managed to recruit the local European super-owners (especially in Italy) to join the scheme. But the scheme foundered because of the power of the fans, who enjoy the pain/pleasure of the current high jeopardy football leagues. TV didn’t get the blame for the resultant furore and the U-turn that resulted… venal American owners did instead. But there were those TV sports fans who were disappointed: the aficionados of technique who just wanted to watch top-flight clubs taking each other on in perpetuity.

The second event of the past weeks was a more TV industrial story. The UK broadband provider BT, decided to sell its subscription sports channels. BT started off life as the Post Office Telephone service, and, like many public services, it was sold off and sent away to carve out a commercial career in the Thatcher era. It retained a significant asset: the nationwide wiring for the phone system that was then used to provide dial-up internet access. As a result, it continues to provide the system that provides the overwhelming majority of internet connections in the UK. Most UK citizens have tangled with the inaptly named BT Openreach which is developing a fibre optic network more slowly than many other countries.

BT had aspirations to be a full service provider, a dream that was recently fashionable among telecoms and cable companies. So BT decided to follow the example of Sky and build its internet TV service on the back of must-see sports… male football again. The bidding for TV rights to league football became a four cornered one: Sky, BT, the cable company Virgin and (with slender budgets) the terrestrial broadcasters. So up went the cost of contracts, largely squeezing out the terrestrial broadcasters, and making English football incredibly rich. More recently, a channel sharing deal with Sky has reduced the costs to viewers. Now, BT have, in effect, thrown in the towel in this rather pointless competition. This may mean the end of super-inflated male football rights auctions, but it is too soon to tell.

What should be clear though, is that sport and TV have an intricately entangled history which continues into the present. What has really puzzled me for a long time is why TV scholarship hasn’t noticed it?

John Ellis is Professor of Media Arts at Royal Holloway University of London. He led the ADAPT project on ‘how TV used to be made’, funded by the European Research Council. He co-edited Hands On Media History (2020) with Nick Hall, and is the author of Documentary: Witness and Self-revelation(Routledge 2011), TV FAQ (IB Tauris 2007), Seeing Things (IB Tauris 2000) and Visible Fictions(1984). Between 1982 and 1999 he was an independent producer of TV documentaries through Large Door Productions, working for Channel 4 and BBC. He is chair of Learning on Screen and an editor-in-chief of VIEW, the online journal of European television history and culture. His publications can be found HERE.