Gerry and Sylvia Anderson began making puppet series for British television in the 1950s, and by the end of the 1960s, their company had made Supercar, Fireball XL5, Stingray, Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons and Joe 90. Anderson’s last puppet series of the decade was The Secret Service, blending live action with puppets in a contemporary setting. Across the decade, puppets and puppetry generated technological innovation in the production of the programmes, puppet performance was developed aesthetically, and puppet adventures expressed the techno-futurist ambitions of the time. Puppets were taken seriously as an effective way to produce profitable television for domestic and international sale. According to Anderson, the export to the USA of Supercar in 1962 saved both his own company and also the distributor, Lew Grade’s ITC, and the fact that all of the 1960s puppet series were screened in the USA by the networks or in syndication affected how they were commissioned, cast and shot. Their action-adventure formats were intended to appeal to both UK and US audiences, they were shot on film because that was how drama was made in the USA, and they used international settings and both British and North American performers.

Fig. 1. A futuristic London Airport in Thunderbirds

Technical innovation

The Andersons studios were in Slough, where numerous contributors worked on puppet and set construction, and special effects. The company made filmed television using film cameras on soundstages, but the use of puppets meant production did not require backlot sets built on the studio premises or shooting in outside locations. Nevertheless the programmes were not cheap or simple to make; with the production of Stingray it became necessary for two crews to work simultaneously on the filming, on two parallel soundstages, and the studio had to manufacture duplicate sets of puppets at different scales. A similar system was adopted to make Thunderbirds, for which episodes were shot two at a time, using three soundstages, one for models and effects and two others for puppet performance. With around 100 effects sequences per episode, Thunderbirds demanded elaborate planning, with up to seven puppeteers at a time on a bridge structure eight feet above the set, controlling the puppets and vehicles. The company developed video assist in 1957 so that the production crew could see what was being filmed, back projection in puppetry was pioneered for Supercar’s title sequence, and proportionately sized puppets were introduced in Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons when the Andersons’ technicians invented tiny solenoids that would fit inside puppets’ heads. They invented electronic lip-synch to precisely match a pre-recorded voice track to the puppets’ mouths.

These innovations were designed to enhance realism, because the cinephiles Gerry and Sylvia Anderson wanted to match live action verisimilitude. They used inserted shots of real hands for close ups, for example, and continually strove to make puppets move like live actors. The focus on futuristic settings and vehicles in the programmes was initially motivated by the Andersons’ dissatisfaction with puppets’ ability to walk convincingly, leading to vehicular movement instead.

Fig. 2. Inside Cloudbase in Captain Scarlet: no walking necessary!

Performance

Settings, vehicles and special effects make up for some of the puppets’ limitations and become performative in the programmes’ telefantastic fictional worlds. So, for example, the title sequence of Thunderbirds gives equal prominence to the Tracy’s vehicles and the family’s members. The places represented in Anderson’s series are diverse, reflecting the reach and effectiveness of the protagonists, who usually work for international organisations with law-enforcement or humanitarian aims. Some environments express 1960s modernity and technology, but there are also atavistic or exotic spaces, and moving between spaces is a key feature of the programmes. The science fictional worlds offer opportunities for the visual revelation of machines and physical action, and vehicles feature prominently. Storylines are constructed around spectacular moments, but also longer effects sequences that showcase technologies in operation. A rolling road and a rolling sky backdrop were invented to facilitate movement and action in vehicle sequences, and a custom-made mix of gunpowder created rocket blasts and explosions. Extended long shots situate vehicles and buildings in large sets, where narrative pace is often generated by editing and music rather than puppet action. Puppet performances are enriched by, and embedded in, a fantasy space that has emotional texture and verisimilar realisation.

The company used voice actors who were American or Canadian, as well as British, primarily to increase exportability, but also with important effects on how characters and performances were created and perceived. In Thunderbirds, for example, the Britishness of Lady Penelope and her butler Parker drew on the cultural meaning of ‘cool Britannia’ in the 1960s. Sylvia Anderson scripted Lady Penelope in Thunderbirds with ‘not only the daring and panache of a secret agent but also the poise of a cool and beautiful aristocrat’, and costume ideas for the puppet were based on Sylvia’s interest in the Carnaby Street styles of 1960s London.

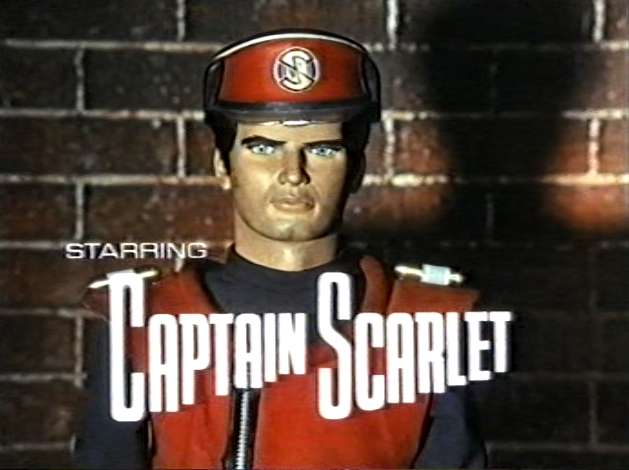

Transatlantic voices included the Canadian actor Paul Maxwell who voiced Steve Zodiac of Fireball and various characters in Captain Scarlet. The Canadian-born Shane Rimmer voiced Thunderbirds’ Virgil Tracy and also appeared in Captain Scarlet and Joe 90. Key puppet characters also facially resemble American film actors, or international stars, because in defining the characters this was an effective way to indicate character to their designers and to viewers. Supercar’s antagonist Masterspy was based on the portly Sydney Greenstreet, and his henchman Zarin sounded like Peter Lorre, thus recalling these actors’ pairing in The Maltese Falcon (1941). The Lorre characterization was reprised for the enemy agent X20 in Stingray, and the series’ hero Troy Tempest was based on the film star James Garner. The character Marina seems modelled on Ursula Andress, seen in Dr No (1962), and Atlanta Shore facially resembled Lois Maxwell, the Canadian actress who voiced her and who appeared in the James Bond films as Miss Moneypenny. Captain Scarlet was intended to signal sophistication, by resemblance to Cary Grant in both the puppet’s facial features and in his voice. The appeal of Anderson’s puppet series depended on aesthetic features in performance that richly referenced popular culture, and compensated for a perceived the lack of nuance in puppet performance.

Fig. 3. Captain Scarlet, modelled on Cary Grant

Making programmes for children using the devalued mode of the puppet series, and the devalued genre of television science fiction, the Andersons could experiment and innovate. The economic success of the programmes fuelled rapid development, and the efficiency of the industrial organization necessary to quickly complete the episodes. The producers tried to find puppet equivalents to realist styles of screen acting and characterizations, matching voice to body both technically via lip-synching and by practices of puppet design and styles of movement. They aimed to take the puppets and their stories seriously. But the puppets’ limitations as performers meant that the other aspects of mise-en-scène, especially vehicles and associated bases like Tracy Island, took on performative characteristics too. In the Andersons’ fictional world, echoing Marx’s theory of the commodity, things are given life.

Fig. 4. Stingray launches from its underwater base

Jonathan Bignell is Professor of Television and Film at the University of Reading. He has written about the Andersons’ series in the collection British Science Fiction Film & Television, and presented versions of this topic at the International Association for Media & History (IAMHIST) and Screen Studies conferences. He leads the research project ‘Spaces of Television: production, site and style’, and his book on space and place in 1960s TV science fiction will appear in 2015.