Like many other lecturers and tutors of media and creative industries courses, I have spent much of the past semester redesigning for online delivery classes intended for face-to-face teaching. In some cases, learning, teaching and assessment were radically altered in order to facilitate students’ submission of work for the semester’s end. Students’ documentary shorts became paper-based portfolios. Students could only write of what they ‘would have done’ in their projects, not of what they did. Those final year students who had spent time developing their professional practice are now faced with fewer opportunities in the creative and media sectors. Us lecturers can, at best, offer messages of sympathy and hope since we cannot anticipate the kind of economy or, indeed, world we will have in six months.

I also happened to be undertaking, over the past year, research of post-secondary school media education in Ireland in order to reflect upon and reassess our own curriculum at Maynooth University where I lecture. This research also forms part of a forthcoming co-authored publication on the various factors that shape media work (such as education, educational policy and industry). Over the past few months I have interviewed colleagues in post-secondary institutions about education in the broader media arts (for example, television, film, digital media, broadcasting, communications). These interviews coincided with the COVID-19 outbreak and subsequent lockdown of both educational institutions and many industries including some television, radio and film production. Interviews inevitably turned to questions about the impact of COVID-19 on students, graduates and media education. One of the questions driving my research – what is media education for? – was considered in part through the lens of this current lockdown. This question seems timely since both media education and media work have been negatively impacted by the lockdown. In some cases, students’ practice work has discontinued for this academic year. Equally, media work such as television and film production has been suspended with no clear sense, in Ireland at least, of when it will return to ‘normal.’ Therefore, it seems a good time to think about what the purpose of media education is, what values and benefits it confers upon students, society and industry, and how we might best prepare media students for life after higher education. I take a brief look here at some of the views on the role of Irish higher education and the relationship between media education, society and industry. I consider some of the concerns media educators raised about the deprioritisation of the social benefits of education in favour of the economic benefits.

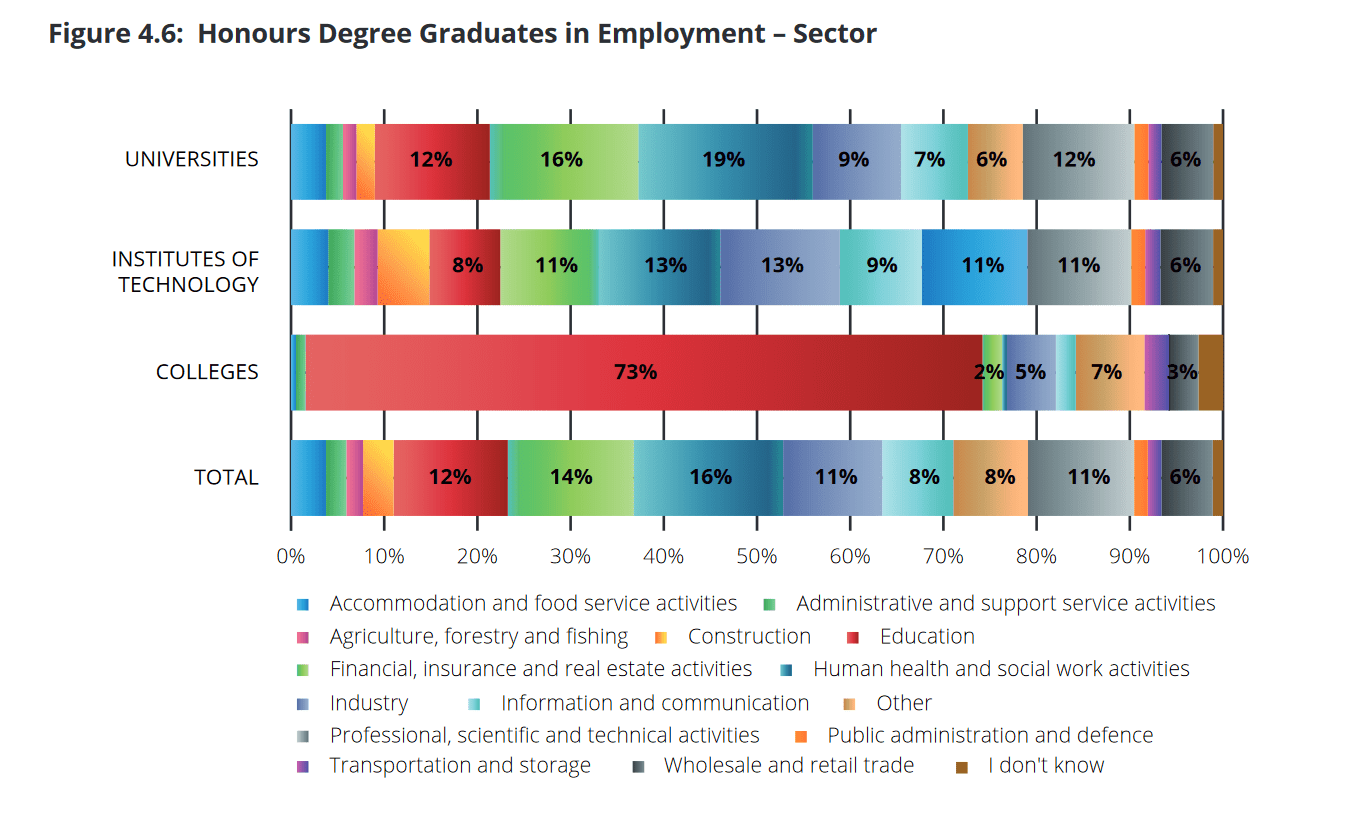

Fig. 1: HEA Graduate Outcomes Survey 2017. Source: HEA.

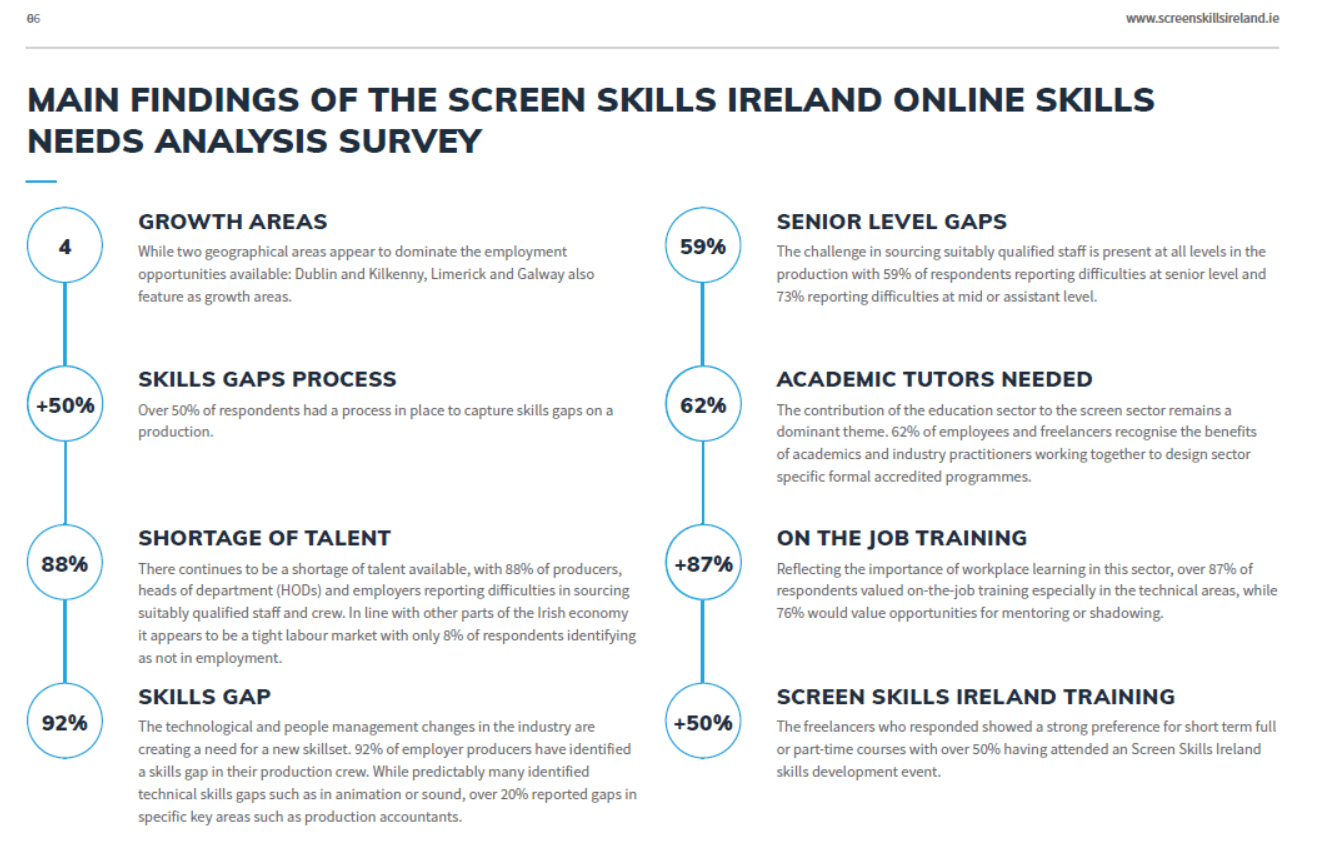

In the case of Ireland, the changing role of higher education – from a social to an economic asset – has come hand-in-hand with policy aimed at generating economic growth through the expansion of, among other industries, the creative industries. As is the case elsewhere, the Irish higher education sector has been increasingly perceived to be in the service of the economy, with education seen as a key driver of economic growth. The discourse on ‘employability’, while not as pervasive as in UK higher education, has played a growing role in the reputational economy of educational institutions. Creative and media education is often susceptible to criticism of producing an oversupply of graduates for sectors known to be challenging in terms of career development (Bridgestock & Cunningham, 2016: 10). Graduate outcomes of higher education courses are often measured in terms of employment or starting salaries, since critical and intangible skills are more difficult to assess. In addition, creative and media education is called up by policymakers and industry to provide the talent pool of workers for the industries and, therefore, perpetuates the notion that educators service – first and foremost – the economy. Especially since the 2008 recession and the Celtic Tiger bust in Ireland, higher education is tasked with ‘earning its keep’ in the Irish economy. For example, in its 2009 report on the role that the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences play in the economy and society, the Higher Education Authority (HEA) along with the Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences (IRCHSS) suggested that arts and creative education (which included media) should engage in “providing the skills for the service sector (including tourism, creative arts, media, etc)” (p.6). In the years since the recession, this narrative of an alignment between creative and media education and the economy has continued to shape policy. From the perspective of industry policy, media education should be streamlined and stripped down to the essential skills and learning required to service the creative sectors. The 2011 Government report, Creative Capital: Building Ireland’s Audiovisual Creative Economy, recommended the establishment of “an Industry and Education Forum to assist in rationalising specific training and education at third level to eliminate duplication and waste.” (p. viii) The report called for an examination of “the match/mismatch of the third level curriculum and the needs of the audiovisual industry” (p. 12). The report also recommended that the Irish Film Board (now Screen Ireland) “take responsibility for coordinating the links between the industry and the second and third level education sectors” (p. 10). However, the Steering Group involved in the report consulted with but did not include any educational providers, nor did it seem to recognise that education serves a wider purpose than just providing talent for the creative economy. This perspective has persisted, with a recent government report on the audiovisual sector drawing attention to the need for “the alignment of [the] education sector to the needs of the industry” (p. 13). Education is here suggested to cause the industry problems of talent undersupply.

From the perspective of educators, creative and media education has a broader remit than servicing the creative economy, although there is a recognition that employability should be one of the key goals of education. While the Review of Creative Arts Programmes in Dublin report of 2013 (HEA) noted that education “contributes more to the individual and society than those things that can be measured financially,” it acknowledged that programmes of study should offer a “reasonable chance of employment” (p. 15). This was especially important, the report noted, since “creative arts and media” courses are more expensive to run than some other courses. In addition, creative arts and media graduates could find employment outside the creative sector, and graduates from other disciplines could find work within the creative sector (p. 17). The report attempted to find a balance between the societal values provided for by creative arts and media education and the expectation (by students, government, and industry) that such education would route students into related employment and work. Ultimately, more connections with industry were recommended and higher education was asked, again, to service the creative industries. Equally, the National Strategy for Higher Education 2030 sets out a mission for higher education that sees the civic and societal directly in relation to the economic. Ireland is understood as having outstanding “cultural arts” that are distinctive and that can be capitalised upon and exploited (p. 51). The Screen Industry Education Forum of 2019 set out to create a programme of education and training that would allow for the cultural arts – in particular, the screen arts – to fulfil this ambition. The Forum reflected a concern with the role of education in providing for the growth of a screen arts sector. Much of the focus of this event and the subsequent report was on the very specific business, craft and technical skills shortages that education and training providers were requested to address. Since the names of media programmes – including Television, Journalism, Film, Broadcasting, Animation, Games, and Digital Media – associate them directly with their respective media sectors (in a way that, say, Philosophy or English do not), there is perhaps a greater expectation that such programmes should prepare students for work in that specific sector, and fulfil a need identified by that sector.

Fig. 2: Screen Skills Ireland Skills gap. Source: SSI.

This close alignment between education and industry may have made economic sense up until recently. Graduate destination surveys associate graduate success with labour market participation. In Ireland, programmes with closer links to industry and graduate employment in the creative industries tend to be the most prestigious. In my interviews with media educators, they noted that students of practical programmes had higher expectations of employment in media work following graduation. They measured their success and the value of their degree in relation to their entry into media work. In a buoyant Irish creative economy, there had perhaps been more opportunity for graduates of practical media programmes to enter media work. However, as Higgs and Cunningham (2008) have noted, graduates of various forms of media programmes are often dispersed across a wide range of sectors, and utilise their education in different ways. But how do we champion the values of non-media work and life if students (and, in some cases, programme promotional material) see media work as the only ‘successful’ outcome of a media degree. In addition, many of the educators I interviewed understood the main value of education in terms that were largely societal, rather than economic. The enhancement of citizenship and the development of individual’s knowledge, social participation, and intellect were considered by some to be the core objective of media education. In this sense, the study of media theory and practice offered an anchor through which students could then participate in and learn from a range of other curricular and extra-curricular experiences (for example, participation in societies or sports, integration into the community, interaction with students from other courses and backgrounds).

This positions media education in the realm of a liberal education where students have the space and opportunities to develop social and cultural capital. Knowledge, critical thinking, political and social awareness, open-mindedness and citizenship were cited in interviews with media educators as important elements of the student learning journey. Once these goals have been reached, students can then think about what they might use this education for. It is clear that such a model of media education is increasingly difficult to justify in an environment in which higher education funding is low but employability expectations are high. Intangible skills and experiences are undervalued since they are not perceived to directly produce job-ready graduates who need little training or mentoring (Rowe, 2014). Media education is seen by some in academia, industry, and the wider public as lacking either critical rigour, technical rigour, or indeed both (Beacham, 2000; Ball, 2003). Some of the media educators I interviewed felt that they were pulled in many different directions, with those in higher education referencing the pressure to produce graduates who were critically aware and knowledgeable, had an understanding of production work and professional life, and had sufficient technical skills and experience to ‘hit the ground running’ in work. Although some of these media educators were able to maintain focus on purely theoretical and academic programmes, many others were developing curricula that leaned towards or centred on production and craft skills and training. Often the ambition was to develop skills and learning that were directly useful in media work and employment. Students in particular sought more employment preparation and training in their media education. However, educators were also conscious that industry demands (for niche technical skills, for example) could not overtly steer curriculum design and development, since such skills did not have much benefit to students outside of a very specific role or context of employment.

Especially now in the midst of COVID-19, graduates face a more precarious immediate future if their media education has been highly specialised and relates directly to a particular role or craft (e.g. cinematographer). As Manuel José Damásio pointed out in a recent CST blog about the impact of COVID-19 on the audiovisual sector and production, this sector was already marked by precarious working conditions. These precarious conditions – “freelance, project-based work, low pay and long hours”- are now even more apparent, such that educational institutions and educators will have to think further about what we are providing for students and what kind of value the educational experience offers them.

If we offer media education in an environment in which employment in the media sector is, temporarily at least, difficult to find, then the employability narrative is difficult to sustain or justify. If media education services the creative economy, would it become redundant during those times when work is hard to come by? We have faced two major economic crises in the past two decades, such that we cannot really rely on economic, employment, or work stability in the future. It may be more of an aspiration than a likelihood. In addition, it may do students and graduates a disservice to measure their success in predominantly economic terms. If graduates understand success solely in terms of their achievement of media work, what then of their personal and academic growth and the societal contributions they make? But, and perhaps I am being defensive here, myself and other media educators I interviewed still have a sense of a greater societal and individual contribution made by media education that gives students the tools by which to think critically and the tools by which to represent and communicate those critical thoughts. I recall two particular instances where graduates I interviewed stressed these somewhat immeasurable values and contributions. One graduate spoke of the way that the study of media had opened their mind and offered them a lens through which to understand social change. The other spoke of how media theory and craft had, over time, become central to how they engaged in social activism. The educational outcomes they describe here are perhaps important to highlight and promote in the current climate of insecurity and vulnerability. During the COVID-19 lockdowns, I have been increasingly asking myself what contributions media education makes, and what the dominant value of it is. I don’t quite have a clear perspective on this at the present moment, and I hope to engage with others from the UK and elsewhere to hear about our shared future as media educators. The case I examine is that of Ireland but, undoubtedly, these issues are international and affect all of us.

I’m eager to hear from and engage with others interested in these issues. Feel free to get in contact with me at sarah.arnold@mu.ie

Sarah Arnold is a lecturer at Maynooth University. She is preparing the book Television, Technology and Gender: New Platforms and New Audiences and co-authoring the book Media Graduates at Work: Irish Narratives on Policy, Education and Industry with Páraic Kerrigan and Anne O’Brien. Her previous books include Maternal Horror Film: Melodrama and Motherhood and the co-authored Film Handbook. Her research focuses on viewing spaces and environments of television and film, particularly in the context of gender and emergent technologies. She is a regular contributor to the Critical Studies in Television blog and RTE Brainstorm.

Bibliography

Bridgestock, Ruth & Cunningham, Stuart. 2016. ‘Creative labour and graduate outcomes: implications for higher education and cultural policy.’ International Journal of Cultural Policy. 22(1) pp. 10-26. doi: 10.1080/10286632.2015.1101086.

Beacham, John. 2000. ‘The Value of Theory/Practice Media Degrees. Journal of Media Practice. 1(2) pp. 85-97. doi: 10.1080/14682753.2000.10807077.

Ball, Linda. 2003. Future Directions for Employability Research in the Creative Industries. Art, Design and Communication- Learning and Teaching Support Network/The Council for Higher Education in Art and Design. Available at: http://adm-hea.brighton.ac.uk/resources/resources-by-topic/employability/future-directions-for-employability-research-in-the-creative-industries-part-4-and-references/index.html [Accessed on 15th May 2020].

Rowe, David. 2004. ‘Contemporary media education: ideas for overcoming the perils of popularity and the theory-practice divide.’ Journal of Media Practice. 5(1) pp. 43-58. doi: 10.1386/jmpr.5.1.43/0.

Higgs, Peter Lloyd & Cunningham, Stuart. 2008. ‘Creative Industries Mapping: Where have we come from and where are we going?’ Creative Industries Journal. 1(1) pp. 7-30. doi: 10.1386/cij.1.1.7_1.