As a currently-peripatetic academic, I often live and travel in areas that are meteorologically interesting. Between growing up somewhere that can give residents all four seasons in a single day (not to mention metres of snow at a time)[1] and then living in a series of deserts, tropical savannahs, highlands and seasides, listening to or watching local weather forecasts has long been an integral part of my daily life. While I rarely stay in one place long enough these days to develop parasocial relationships with any of my (temporarily) local meteorologists, that parasociality is key to the development of audience trust (Henson, 2010; Beattie, 2023). That trust, then, becomes key to providing information during severe weather which the audience will then act upon. This is a topic I have researched and continue to study, mostly with regard to digital weather media (Beattie, 2023); for this blog, however, I would like to focus on some of the key textual and paratextual elements that develop these relationships and how these can be leveraged to (ideally) improve weather education and dissemination to the wider public(s).

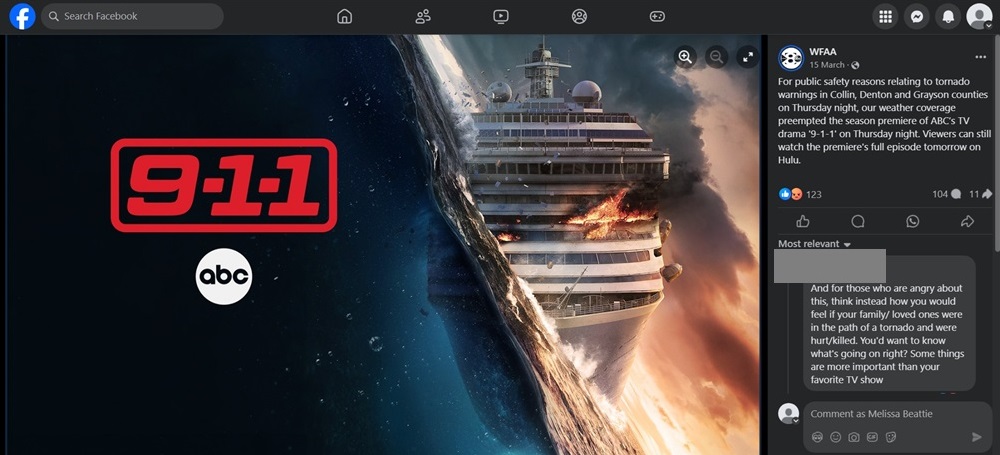

To begin, I will address the metaphorical elephant in the room: my work thus far looks at Anglophone weather media (broadcast and digital) in mostly developed countries. I hope to broaden that at some point if it becomes possible; in addition to the obvious need for funding, in some of the most meteorologically interesting/climatically vulnerable parts of the world, journalism and/or environmental activism are unwelcome (to put it charitably); so, this type of study may not be possible in these areas. Thus for the purposes of this blog I will focus upon severe weather reporting based in the US. While political polarisation in many parts of the US does cause a backlash against climate journalism, as I presented at this summer’s CST conference, for severe weather the main complaints I heard referenced during terrestrial broadcasts over the spring and summer of 2024 relate to the severe weather coverage pre-empting regular programming. This is primarily due to local broadcast stations having a specific coverage zone which can cross a wide area and the fact that the American National Weather Service (NWS) regional offices generally issue warnings by county[2] rather than city. Meteorologists are seemingly obligated to explain this, though because most of the major terrestrial broadcasters have additional cable (and sometimes free-to-air) channels the normally scheduled programming can be shunted to those channels for anyone who does not need or wish to watch the weather coverage. This can be thought of as a way of mollifying viewers outside the warning area whilst still meeting journalistic obligations to the public good. As my work on stormchasing and trust shows (Beattie, 2023), adherence to and perceived primacy of the public good over private good (in this case, profit) is a major reason for audience (dis)trust of a given weather news outlet. Severe weather coverage, at least for tornado warnings, is generally ‘wall-to-wall’ (i.e., without advert breaks) on broadcast stations. Through reading comments on recorded severe weather coverage of American cable broadcaster The Weather Channel (TWC) that was subsequently posted to YouTube by fans, the fact that TWC rarely engage in wall-to-wall coverage any more is a source of frustration which is then usually tied to an increasingly negative view of the channel. While a full study would be needed to prove this, the comments broadly match my stormchasing study on negative perception of outlets that seem to be moving or have moved away from the ‘public good,’ here meaning safety of the viewers within the outlet’s catchment area.

During such continuous coverage, the local meteorologist can function as someone both of the community (broadly defined) and as an authority figure in (temporary) charge of it. This can be read as a form of affinity (Carlin and Love, 2013) which would engender trust and reinforce the parasociality developed through regular (parasocial) interactions when audience members watch daily forecasts when there is no danger of severe weather. The trust and affinity, which can be augmented ‘if the members of that group consider themselves to be socially marginalized’ (Austin, 2004: 365) as can be the case in many meteorologically/climatically vulnerable regions, is then maintained and reinforced throughout the emergency. While part of this is accomplished by the wall-to-wall coverage discussed above, it is a common feature of broadcast meteorologists to state that they/the meteorology production team will ‘stay with’ the audience until the severe weather threat has passed. This is then reinforced by reminding the audience of whatever forms of simulcasting the particular station has available (additional television channels, radio, streaming, etc) in case the audience suffer a power cut due to the storm.[3] Because of the negative impact of perceived weather ‘hype’ (sensationalism) with regard to trust (Beattie, 2023), the combination of the above can, at least in theory, encourage viewers who are in danger from severe weather to take the action(s) broadcaster meteorologists recommend. Though the use of User Generated Content (UGC) in journalism can be somewhat contentious (Ambrose, 2024) in this instance it serves two functions. Henson (2010) and Whittaker and Clark (2021) have both shown that one reason people will sometimes endanger themselves by going to a location under weather threat is to confirm the severity of the threat (and, in some cases, its presence, location and/or movement). The supplementation of the outlet’s own field reporters (often a dedicated team and/or freelance stormchasers) with UGC can help ameliorate that perceived need through showing either real-time or recent footage, thus ideally preventing people from putting themselves in harm’s way. The fact that the trusted outlet is showing it is perceived as a sort of ‘quality control’ by audiences (Beattie, 2023). But that fact that the UGC comes from those living in the viewing/threatened area and is being shown on local outlets (as opposed to national or transnational ones) also reinforce the sense of community through simultaneity (Anderson, 2010) while also reinforcing the community member/leader status of the local meteorologist.

Though we often talk about ‘the public’ in both lay and academic speech, it is more accurate to consider them as plural, heterogenous publics, rather than a singular, homogenous public. Yet journalism, as the Fourth Estate and a critical part of a functional democracy, is inextricably bound to the concept of a ‘public good.’ The attempt to inform and protect those viewers nominally in range of one’s broadcast, though an archaic metric given the potentially global reach of a livestream, can be thought of as transcending the differences in those publics. Though infrastructure correlated with socioeconomic and sociocultural status does impact an area’s vulnerability, dangerous weather is a threat to all. In an increasingly polarised environment, having trusted authorities advising those under such a threat can save lives which does unequivocally serve the public (and publics’) good.

Dr Melissa Beattie is a recovering Classicist who was awarded a PhD in Theatre, Film and TV Studies from Aberystwyth University where she studied Torchwood and national identity through fan/audience research as well as textual analysis. She has published and presented several papers relating to transnational television, audience research and/or national identity. She is currently an assistant professor of liberal arts at Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane, Morocco. She is under contract with Lexington for an academic book on fictitious countries and Palgrave for a book on Canadian crime dramas. She has previously worked at universities in the US, Korea, Pakistan, Armenia, Ethiopia and for a brief time in Cambodia. She can be contacted at tritogeneia@aol.com.

Footnotes

[1] Western New York State.

[2] Counties in the US can vary widely in size. Maricopa county in Arizona, where I sometimes live, is approximately 23,890 km2 . This is slightly larger than Wales.

[3] Most news facilities also have emergency generators to allow them to continue to broadcast/simulcast if their own power is cut.

References

Ambrose D (2024) Social and mobile media in times of disaster. In Wake A (ed). Transnational Broadcasting in the Indo Pacific: The Battle for Trusted News and Information. Cham: Palgrave, pp. 135-158.

Anderson B (2010) Imagined Communities 3rd Ed. London: Verso.

Austin D (2004) Affinity Fraud in the African American Church. University of Maryland Legal Journal of Race, Religion, Gender & Class 4: 365-410.

Beattie M (2023) ‘In it for the money, not the science?’: Problems and potentials of stormchasing media. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies, online first, https://doi.org/10.1386/ajms_00104_1 .

Carlin R E and Love G J (2013) The Politics of Interpersonal Trust and Reciprocity: An Experimental Approach. Political Behavior 35(1): 43-63.

Henson B (2010) Weather on the Air. Boston: American Meteorological Institute.

Whittaker J and Clark A (2021) Research to improve community warnings for bushfire. Australian Journal of Emergency Management 36(1): 13-14.