Gosh – aren’t there a lot of books about Doctor Who (1963-1989, 1996, 2005-)?

Admittedly, that’s a thought which I had recently when standing looking at a wall in Galaxy 4, a shop in Sheffield that for 26 years has been specialising in the sale of Doctor Who-related merchandise to the world in general and my wife and myself in particular, but, nevertheless, you suddenly realise how the sheer volume of volumes – even for a programme of that longevity – does seem a little disproportionately, enormously, vastly huge.

I mean, I have a massive passion for the Time Lord’s escapades… but I do kind of like to read books about other stuff once in a while.

And I know that these adventures in space and time are not short of worthwhile material for study. There’s a lot of technical and cultural stuff in there for the world of academia while, as I think I’ve mentioned before, I’m largely in it for the monsters and the spaceships. I also understand that commercial books must make money, and that academic books frequently need to earn citations – thus in both arenas there is a very understandable tendency to stick to tried and trusted subject matter.

But the fact of the matter is that there’s a whole slew of other very good, very worthy, very entertaining, very important series out there that don’t get any books at all. Of course, tie-in books about a series tend to be published when it is on-air and ‘hot’… which is why I have shelves filled with tomes such as The Quantum Leap Book by Louis Chunovic (1993), a perfectly engaging work which sadly doesn’t cover the show’s final season… presumably because by that point the audience had dwindled and nobody invests in a licence for a cancelled show purely to bring a publication up to date for me to enjoy.

Thankfully, that’s not stopped enterprising enthusiasts over the years though. Susan E Kessler’s The Wild Wild West: The Series (1988), John Heitland’s The Man from UNCLE Book (1987), Andy Priestner’s The Complete Secret Army (2008), David H Schow’s The Outer Limits: The Official Companion (1986), David Brunt’s ongoing BD to Z Victor 1 series chronicling Z Cars (2014-), Mark Dawidziak’s Night Stalking (1991), Richard Marson’s Inside Updown: The Story of Upstairs Downstairs (2005)… and countless others, all there ready to captivate me with their facts and fun, fuelled by adoration for their subject.

So… why can’t I get a decent book about Moonlighting (1985-1989)? Or Hill Street Blues (1981-1987)? These were major series in their day and highly influential. But they seem to have vanished off the face of the Earth when compared to the cultural impact we were assured that they were having at the time.

Yes, I know that we have Barbara and Scott Siegal’s Cybill & Bruce: Moonlighting Magic (1987)… but only about a third of it is actually about the series. And, yes, I agree, there’s a couple of chapters in the BFI’s MTM: Quality Television (1984). But I mean, really, come on… it’s not like I’m asking for texts about fleeting gems like Virtual Murder (1992) or Oliver’s Travels (1995)[i].

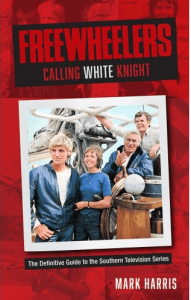

As I noted previously, one of the things that delights me immensely is when people bother to take the time to look at things that aren’t the usual suspects. It often won’t make them terribly rich – or earn citations – but I think I love them all the more because of that. And that’s probably why my reading during the dying weeks of 2019 was all the richer for the publication of Mark Harris’ Freewheelers: Calling White Knight (2019).

For those of you from outside the UK or living in BBC-worshipping households or under the age of 40 and without access to the Freeview channel Talking Pictures TV, let me explain about Freewheelers (1968-1973). This was a rather successful set of children’s adventure serials made by Southern Television in which youngsters just old enough to hold driving licences were seconded by MI5 or MI6 (depending on attention to continuity) to fight all manner of global threats posed by new, science-bending inventions which seemed to continually fall into the hands of a string of neo-Nazis, would-be-dictators and all-round-negative-vibe merchants.

The show – or what there is of it still in existence – remains deeply impressive because of the scope and vision of its creator and producer, Chris McMaster – or “That lunatic who goes off shooting stuff on film without a script and hopes to stitch it together in studio” as one of his contemporary colleagues once described him to me. Never has an adventure series felt less inhibited by its finance – favours were pulled with influential mates, hardware was begged, borrowed or stolen, and other sequences shot with scant regards for modern health and safety… all packaged with often the slenderest of narrative logic into a thrilling slice of childhood escapism. It was Bond on a budget.

All these years later, Mark’s book chronicles the series’ development, production, broadcast and reception. It talks to the cast and crew. It presents long-forgotten paperwork. It catalogues filming locations. It even lists library music cues. All wrapped up with a great deal of love and enthusiasm for a particularly breathless, endearing kind of hokum. How lucky are we to have a piece of research like this on what is a comparatively obscure television series? I think we’re very lucky indeed that anyone should even bother…

Now, one of my bad reading habits is that I’m often so eager to jump into a newly-acquired volume that I’ve hoped for years somebody would write about a given show that I just dive straight in wherever I want. With Freewheelers: Calling White Knight, I picked up the story with Chapter Five on page 32 – where work on Series One gets underway. Stacks of good stuff here for me to enjoy. I’m devouring this thinking ‘Gosh – this is brilliant! Feels like it’s written just for me.’

By the time I’ve got to Chapter Seven without pausing for a comfort break, I ruminate that maybe it’s time for me to start this book again properly the way that I’m meant to. So, I go back to the start and read the Introduction. To my astonishment, on page xviii is a paragraph by Mark in which he reveals that a major factor in him writing the book that I’m reading is that he met me at an event in 2017 and I told him that it was the sort of book that I wanted to read and that he should write it.

So… maybe not so lucky after all. I get the book I want to read, partially because I ask somebody to write it for me.

Well, I’ve now discovered that Moonlighting: Cases, Chases & Conversations by Scott Ryan and EJ Kishpaugh is due out later this year. I’ve also confirmed in my mind how and why some series get to have books and others don’t. And – as such – there’s only one question left.

Which of you is going to write me a book to read about Hill Street Blues? Ideally by the end of the year please.

Andrew Pixley is a retired data developer. For the last 30 years he’s written about almost anything to do with television if people will pay him – and occasionally when they won’t. In 2009, he and his wife had to have an extension built at the back of their home… partly to house all the books they keep buying about increasingly obscure television shows. And now they have one more. Book that is – not home.

Notes:

[i] But, yes, I wouldn’t mind reading those either actually… If you’re not doing anything…

Aware of my lead image for this blog, I’d just like to add an RIP for Robert Conrad who died yesterday at the age of 84. “The Wild Wild West” remains one of my favourite slices of 1960s adventure hokum, and the fact that Bob Conrad had been a former stuntman meant that he was not only a very watchable, charismatic lead actor, but that the action sequences were invariably a cut above all others of their type. It was always so exciting to see Jim West burst into action and know that almost always the incredible feats of strength and dexterity were actually being performed by the show’s star.

All the best

Andrew

Fascinating reading! It’s truly an oddity what TV shows live on and which ones die a death. (I admit to still having a fondness for my meories of “Moon and Son” and Channel 4’s “Nightingales” and “Chelmsford 123” , all of which seem to have vanished into the mists of TV history. Perhaps the current situation will lead to bored 40+s asking “whatever happened to……” and a few old shows being dusted off. It’s been a very long time since the days of the LLG Dr Who-related madness, but I’ll remain eternally thankful for your introducing me to “Sapphire and Steel” and “Edge of Darkness”!

Ruth

Dear Ruth,

Sorry – how rude of me not to reply earlier to your very kind posting. I wish there was some way that there was an alert to say that somebody had posted a response or a comment because interaction and feedback is pretty thin on the ground, and when somebody *does* take the time and trouble as you’ve done here, I should *really* be saying “Dear Ruth, Thank you for taking the time and trouble to comment with your kind remarks.”

Thank you for taking the time and trouble to comment with your kind remarks [i]. “Moon and Son”! Goodness – yes! I remember interviewing Chris Boucher the week he took over as script editor of series two of that… so, obviously, history tells you that that wasn’t a story with a happy ending. I have to admit that Gladys and Trevor were good fun, but something about their investigations never *quite* clicked… added to which, if memory serves me right, Frank Muir was curating “TV Heaven” on Channel 4 the same night…

“Nightingales” is bliss. We’ve just watched the whole run on ForcesTV. My wife had never seen them before and she fell in love with this surreal recipe instantly. It would be lovely to revisit Paulinus and Badvoc back in AD 123 again as well – does memory serve me right that the TARDIS dropped in on one episode?

Hope all is well with you and the family, that you’re safe at this rather unsettling and awful time, and delighted that over the years you’ve been able to enjoy medium atomic weights being assigned and Craven and Jedburgh exposing nuclear secrets.

Take care.

Andrew

[i] There we are – that’s that bit done.