Television has long been accused of creating zombies….breeding an audience that sits transfixed in front of their TV screens, hypnotized by the presumed-to-be mind-numbing qualities of this ‘mindless’ entertainment. This idea continues to haunt popular culture, so much so that it has been used, quite ironically, within such cult TV series as Angel (WB 1999-2004) and Doctor Who (BBC1 2005-) to comment upon the negative potential of television. In Doctor Who’s ‘The Idiot’s Lantern’ (2.7) and Angel’s ‘Smile Time’ (5.14) aliens and demons and respectively use the networked capabilities of television to drain the human life force from the TV audience in order to feed their own hunger for power….a cynical commentary on the status of corporate television [particularly poignant in the case of Angel as this episode was aired just a few days after the show’s cancellation was announced]. In ‘Idiot’s Lantern’ an elderly woman even goes so far as to warn her grandson ‘I hear they rot your brains…rot them into soup and your brain comes pouring out of your ears…that’s what television does’ [ironically the opposite of a zombie whose brain is active while it is its body that rots but hey-ho the metaphor still works and rotting brains would appeal to any zombie].

In both of these episodes, television does in fact create zombies. Of course, much scholarly work has been done to challenge the assumption that television is mind-numbing, inviting passive consumption [although zombies never really consume anything passively] over active viewing. It is not, therefore, my intention to use this blog to interrogate the zombification of TV audiences. Instead I am more interested in the zombification of TV. TV seems to be obsessed with the undead. Last year, I wrote a blog on the TV Vampire, but now my mind turns to the zombie [yes I’m diversifying] which seems to be popping up everywhere on our TV screens. In addition to a long history of monster-of-the-week appearances in horror series such as Night Stalker (ABC 1974-75), The X-Files (Fox 1993-2002) , Buffy the Vampire Slayer (WB/UPN 1997-2003), Angel, and Bloodties (Chum Television 2006-2008), the zombie has been used as bitin g political satire about the Bush administration and the war in Iraq in Joe Dante’s ‘Homecoming’ (1.6), an episode of Showtime’s Masters of Horror (2005-2007); they have taken over the Big Brother House in Charlie Brooker’s critique of reality television Dead Set (E4 2008); and they have been restored to their voodoo origins as a commentary on social and racial slavery in American Horror Story: Coven (FX 2013).

Zombies hover on the periphery of the hugely popular fantasy series Game of Thrones (HBO 2011-) as the threat of the White Walkers continues to loom across the show’s narrative – they have so far only made the occasional appearance but they are an ever constant and ambiguous threat.

The French series Les revenants (Canal+ 2013-) (soon to be remade in the US) explores the emotional impact of a community who must face the uncanny return of their dear-departed. The dead in Les revenants are not zombies as we know them for they have seemingly returned from the dead unchanged, appearing at the locations of their deaths (wearing the very clothes they died in) rather than crawling from their graves and showing the ravages of decomposition. This series does not confront us with the literal horrors of death and mortality but rather with a series of uncanny encounters between the living and the dead, such as :

identical twins now separated by years as one has aged while the other is frozen in time;

The Returned

a creepy child who died thirty years ago and now blurs the lines between innocence and an all too-knowing maturity;

The Returned 2

a woman so numb from the trauma of brutal attack that she questions whether she might in fact be the dead returned.

The Returned 3

The choice of title for this series is fascinating as its French title Les revenants evokes the folklorist term for any dead, whether ghost or corpse, that returns to haunt the living while The Returned suggests the uncanniness of the return of the repressed. This show embodies it all.

The Returned 4

Each of these texts offers their own spin on the zombie and the precise significance and meaning of the zombies in Game of Thrones and Les revenants have yet to be revealed for these are ongoing serial narratives, ideally suited to the televisual format. These zombies are holding their purposes close to their chests. In our book TV Horror, Lorna Jowett and I argue that in many ways the zombie is an ideal figure for serial storytelling as the zombie apocalypse does not happen with a big bang but rather marks the slow decline of society and humanity, something Robert Kirkman identified in his conception for the graphic novel The Walking Dead. The traditionally ninety minute structure of the cinematic feature can only really hint at the true horror of this apocalyptic end of humanity which lies in the day to day struggle. Of course, zombie film franchises such as Resident Evil, 28Hours/Weeks Later, and George Romero’s Dead series suggest seriality as each film offers a glimpse of an ongoing global outbreak. When looking at each franchise as a whole they do construct a much bigger representation of an ongoing apocalypse, but each film is primarily telling a self-contained story about particular pockets of survivors or various stages of the outbreak. Resident Evil is the only franchise that offers a continuous narrative by following the ongoing story of its main protagonist Alice (Milla Jovovich). This narrative is however somewhat limited, partially owing to the franchise’s origins as a video game, for the narrative often reverts to the beginning in order to reboot the story and take Alice to a new gaming level.

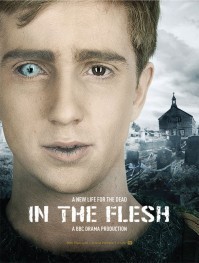

The TV series The Walking Dead (AMC 2010-) and In the Flesh (BBC3 2013-), however, are both entirely structured around their ongoing serial narratives, utilised to explore the gradual crumbling of society after the initial outbreak, or rising, that caused the dead to return in droves and they do so from radically different perspectives. If The Walking Dead is about the horrors of survival amidst the breakdown of civilisation, then In the Flesh is about the horror of infection, finding yourself alienated from your family, community and even your own body and personal identity. It embodies the horror of death in all of its facets

.

The Walking Dead In the Flesh

As illustrated by the above posters, The Walking Dead follows a group of human survivors lead by Deputy Rick Grimes while In the Flesh focuses upon recovering zombie (or Partially Deceased Syndrome sufferer) Kieran Walker – an innovative contribution to the growing trend of ‘I, Zombie’ stories across film, literature and now TV (see Warm Bodies, Colin, Husk and iZombie for other recent or upcoming examples). These different perspectives allow each of these series to offer a unique approach to the genre but both offer a stinging critique of the worst of humanity. On The Walking Dead, the survivors must repeatedly fight for their lives, against both ‘walkers’ and humans, while struggling to resist the gradual stripping away of their humanity. The series confronts the audience with questions about what it means to be human in a world where violence is the order of the day and where there is a rupture between morality and pragmatism. The series oscillates between a seeming celebration of weaponry – even children learn how to use weapons in order to survive (imagery that is particularly poignant and unsettling given the ever constant debates about gun laws in the US) – and a condemnation of the damage that can – and will be caused – by these attitudes. For instance, the scene where Rick’s son Carl shoots a teenager from the rival faction of Woodbury as he surrenders (‘Welcome to the Tombs’ 3:16), brings home the horror of the mentality that prioritises self-defence at all costs.

Carl’s explanation that he did what he had to do because this boy might one day be a threat is coldly pragmatic and decidedly soul-less. But while our natural inclination is to condemn Carl for his actions (as both Rick and the sage-like Hershel do), the show does not make the situation quite so clear cut. This episode contrasts Carl’s decision to kill the boy with the results of Andrea’s choice not to kill the Governor (the leader of Woodbury). In a move that highlights Andrea’s development across three seasons from a kill or be killed attitude to an emissary of peace, Andrea decides not to play assassin by killing the Governor in his sleep and instead tries to find a peaceful solution to the war between Woodbury and the Prison. The result of her hesitation is not only her own death, but the deaths of a large number of her friends from both groups, all of whom might have been spared had she murdered the Governor… or would they? Would her act of violence simply have led to more violence? It is impossible to know. The tension between traditional morality and the pragmatism that is presumed to be necessary in this new world continues to raise questions. Most importantly the show asks, does the potential benefit of violence (saving our skins) outweigh the gradual degradation to humanity through its execution (ie. how can we live in our skins?).

This is a question that is raised in the second series of the BAFTA-winning British series In the Flesh through the character of Jem Walker, a teenage zombie-hunter now acclimatising to a post-post zombie apocalypse where the outbreak has been contained, and zombies, including her brother Kieran, are being treated and rehabilitated back into society. While season one presented Jem’s survival and success as part of the Human Volunteer Force as fuelled by burning anger and teenage rebellion, season two highlights the post-traumatic stress of her experiences killing zombies. When confronted by a rabid PDS sufferer at school, Jem panics and humiliates herself by losing control of her bladder and attempting to flee the scene. [Spoiler Alert] Later she over compensates for her seeming failure by shooting a harmless teenage PDS sufferer who had a crush on her, mistaking his drunken rambling home through the woods to be a sign of a rabid zombie. While the local MP Maxine Martin chooses to brush this event under the carpet, saying Jem deserves a ‘free pass’ for all that she did for the community, Jem struggles with the impact of her guilt both for this crime and for all the zombies she killed during the Rising—guilt made all the more tangible when she meets the daughter of one of the zombies she ‘put down’. In the world of In the Flesh, every zombie is someone’s family and as a result the pragmatic destruction of zombies that is a natural part of The Walking Dead world is called into question.

In fact season one of In the Flesh is all about grief and loss as families are forced to confront their grief by coming face to face with their much-loved departed, whose continued undead existence is a reminder of their initial painful demise…[Spoiler Alert] Kieran still bears the scars of his suicide. This theme of loss is also explored on the Walking Dead as each of the series’ protagonists lose much loved members of their family [Spoiler Alert: Andrea loses Amy and Dale, Carol loses Sophia, Rick loses Lori, Daryl loses Merle, and everyone loses Hershel]. These loses are doubly significant as they not only impact upon the characters within the narrative but also the audience who have become emotionally involved with the characters as the narrative unfolds on a weekly basis (see my blog on the Horror of Grief for a further discussion of this].

In contrast to season one, season two of In the Flesh is about acceptance (or lack thereof) as the community deal with the long term problems of integration. While the opening episode suggests that the community of Roarton has healed and is prepared to move on, the arrival of Maxine Martin –an MP from the anti-PDS Victus party, cracks that façade and reveals the fissures and tensions that run through Roarton. This season highlights the community’s fears and prejudices alongside the PDS sufferers’ growing feelings of marginalisation and discrimination. While not endorsing acts of terrorism, the series offers a bold examination of how and why prejudice and social alienation leads to radicalisation, while also questioning the motives of those who are preying upon those experiences in order to radicalise the community.

There is much to be said about both shows’ contribution to the development of zombie TV and I have just begun to scratch the surface. But I wanted to conclude with consideration of the character of Amy Dyer, the show’s lead female PDS sufferer. In a bleak post-apocalyptic landscape of anger, prejudice and hostility, her self-possession and confidence is a sign of hope for the future. She is the first PDS sufferer within the community to shed her cover-up make up and contact lenses, confronting others with the reality of her condition and urging acceptance on both sides. (Amy is shown examining her features in the mirror in season one while Kieran continues to cover the mirrors as he applies his cover up in season two). The contrast between Amy’s undead features (pale skin, dark lips, bleached eyes) and her colourful and excessively femme dress sense, calls to mind Goth fashion and Amy is the victim of much of the disdain, discomfort and abuse with which Goth subculture is all too familiar. But Amy, in all of her undead-ness, embraces life more than any other character and celebrates love, friendship and social acceptance. She is a breath of fresh air within a bleak social landscape, repeatedly pictured frolicking and having fun whether in amusement parks with Kieran, dancing at the Undead party, or playing Crazy Golf with Philip (a locale councilman whose prejudice is gradually worn away by Amy’s effervescence). While occasionally dismissed by Kieran and undead apostle Simon as frivolous, I would say that she is deeply self-possessed. I write this a week before the final episode is aired and I don’t know what is going to happen….but it seems to me that Amy might offer the much needed path toward healing within the community.

Whether the violence and prejudice will go too far and make that journey impossible, we will have to wait and see. Anything can happen and I doubt it will be all neatly resolved. There is nothing neat and tidy about a zombie apocalypse after all.

But in the meantime, I am still thinking about zombie TV and hope you will too….for there is much that remains to be….[Yes I’ll say it] unearthed.

Stacey Abbott is a Reader in Film and Television Studies at the University of Roehampton. She is the author of Celluloid Vampires (2007) and Angel: TV Milestone (2009), and co-author, with Lorna Jowett, of TV Horror: Investigating the Dark Side of the Small Screen (2013). She is also the editor of The Cult TV Book (2010) and General Editor of the Investigating Cult TV series at I.B. Tauris.