While I have always been an avid television viewer, I have found that my content consumption behaviour has changed drastically; before I arrived at University in September, I was watching more television than ever before. This was mainly due to the reduced levels of physical contact with my friends but also due to a wealth of undiscovered programmes on streaming services.

As we were all unable to socialise in face-to-face scenarios there has been a major upshot in the number of digital social meetings that revolve around content on streaming services. One such web application called ‘Netflix Party’ allows several users to watch a TV programme in synchronicity and share their ideas and emotions. This app allows friends and family members to watch content at the same time and feel as if they are ‘in the room’. For me, this such activity would feel natural as I am a millennial that has grown-up with technology and the freedom to communicate in a digital space. My parents’ generation understandably may have a lack of knowledge on how such systems would work and could feel uncomfortable with watching television in this way.

Although people are still staying in contact with friends and family members and keeping their emotional and social relationships intact, the lockdown could have some implications in that audiences have formed dependencies in content consumption. I feel that my levels of content consumption doubled, if not trebled during the lockdown period as I was unable to leave my household. I will admit I am a huge geek and love playing video games but even after playing for hours, I choose to ‘wind down’ and relax by diving into a new box set. This would be okay in normal circumstances but when one prioritises watching content over essential work or friends this is, in part, a form of socio-isolation.

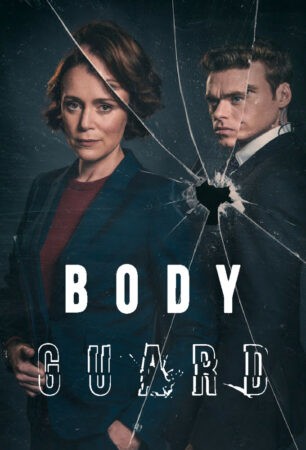

In the first section of my lockdown, at home, I found myself subscribing to Disney + and re-watching all the MCU and Star Wars franchise films. This was quite a time commitment and required many hours of viewing. I understand during this testing time that I was unable to go out and meet people due to governmental restrictions but on reflection, I am still questioning my viewing decisions and feel that I could have possibly reduced the number of shows I chose to binge-watch. A surprising discovery I watched during the summer of 2020 was The Bodyguard (BBC, 2018) This show was written by Jed Mercurio the writer who also created Line of Duty (BBC 2012 – ). This series, probably more than any other, inspired me to want to create television that engages an audience, in a fairly traditional way; in a sea of ‘dropped content,’ these two series were still able to provide those ‘water-cooler’ moments for audiences increasingly distracted and immersed in a fragmented content stream. The Bodyguard’s compelling narrative, paired with complex twists, made me want to watch episode after episode and luckily, I could! – even if I should have been doing other work….

Moving from a household setting to a University halls-of-residence has also given me a wider perspective on how students choose to consume content. In my recent experience, many students living together in Halls will work late into-the-night on their coursework and have little time to watch their favourite programmes. I have not watched anything on Netflix since I arrived in Bournemouth as I have chosen to focus on things I deem more relevant. Work and pleasure need to be balanced of course but I find myself prioritising socialising rather than sitting in to watch a new episode of a show.

Television consumption has changed a great deal in the last 10 -15 years, and linear formatting and the dominance of the schedule has diminished. Audiences demand flexibility and the ability to pick and choose when they watch content and what device they consume said content on. But, as a student studying Television Production, the lockdown and my ever-shifting patterns of viewing have led me to question the very definition of ‘television’; is it the device you watch programmes on, or the content? I primarily watch programmes on my computer monitor in my bedroom, and I watch just as many films on streaming services as a drama and documentary series. I have also come to value social interaction, above personal content consumption. I am not suggesting here that every University student does not watch TV or films, all I am suggesting that, in my experience, polarising circumstances have had an inverse impact on hours watched within the University setting.

Finally, I have been thinking about what the creative industries will look like when I graduate in 2023. Footfall for physical cinema locations has fallen to such an extent, the new James Bond film, No Time to Die (Cary Joji Fukunaga, 2021) has had its release date pushed back so far, that a major UK cinema chain – Cineworld – is close to collapse. More film releases are being shifted onto VOD platforms, further blurring the already contested distinction between cinema and television. This is a key example of how unforeseen circumstances can change the distribution of media content. As a media student, I hope my studies will help me negotiate this new world, but I am already convinced that the ways in which television is consumed, have changed forever.

I hope all CST readers and contributors are staying healthy and well and I wish you all the best in today’s testing times.

Matthew Price is from Hertfordshire and is in his first year of the BA (Hons) Television Production programme at Bournemouth University, UK.

Dear Matthew,

Thank you for a brilliant and engaging read – particularly your disovery and delight of “The Bodyguard” which – I agree – was a cracking piece of television. And even moreso when you say how it’s inspiring you for your own future. I remember a few years back when “Broadchurch” was riding high in the charts for ITV that Chris Chibnall was being interviewed on the radio and how he explained that he’d been inspired by things from the 1980s such as “Edge of Darkness”. And to hear somebody writing that they want to make television as captivating as “The Bodyguard” is a joy to read… if only because it means that my wife and I can enjoy watching it at some point in the future!

And so fascinating to read about your experience of viewing as you go from home to uni and to compare it with my own back in the 1980s. Because, of course, I went from a home with two TVs and one video recorder… to a campus where there were three communal TV rooms a short walk away unless you happened to know somebody with a portable TV in their room… and even if they had the reception was so awful without an external aerial that you may as well forget it. As such, I was reliant on limited visits to the TV rooms for ‘essential viewing’ (generally “Doctor Who” and the odd re-run of “The Sweeney”) and everything else was being backlogged on Betamax at home for monthly weekend catch-up viewings… after which the tapes could be reused.

(Luckily, the engineering course meant that I was sponsored… and being sponsored meant that I could save… and with my savings in the first year I bought a portable TV and while working in industry for my sponsors that summer I saved for a Betamax SL-F30… so subsequent years in tertiary education meant that I missed less…)

I hope that you are also safe and well down in Bournemouth, that you still get the very most you can out of higher education in a situation that I can’t even imagine, and that at some time you get to explore the rather amazing IBA Archive stored down there.

Looking forward to enjoying all the programmes you make after your graduation.

Take care and make the most of it all. It sounds as if you will.

Andrew

Thank you for your kind words, Andrew!

Current situations have not only changed the way I consume content but also how I study – in this changing circumstance I am still trying to make the most oof the situation.

Wish you all the best

Matthew