In our last blog post, we examined the acting by a female performer in a strong ensemble cast – Jennifer Aniston in Friends (NBC, 1994-2004) – and today we will do the same again. This time, we are shifting from the production and genre contexts of US network sitcom to US cable half-hour medical dramedy: namely, Nurse Jackie (Showtime, 2009-2015), which at the time of posting will be rapidly approaching the broadcast of its series finale. We have decided to not focus our attention on the series’ lead Edie Falco, notwithstanding the fact that she is a gifted actor, whose performance of inscrutability in this programme is interesting and interestingly discussed by Janani Subramanian (2012). Instead, we will concentrate on Merritt Wever, who has rightly gained praise and an Emmy award for her portrayal of nurse Zoey Barkow. A selection of moments of Wever’s acting on the show can be enjoyed here:

As the ‘Scrubbing in with Zoey’ Showtime feature demonstrates, Wever really owns the part, and we have chosen to closely examine a short scene from episode ‘Game On’ (3.01) to attend specifically to how Wever draws on animalistic properties to inform her characterisation and acting choices. We are far from the first to make links between Wever’s performance as Zoey and various animals, as the following quotations attest: Nancy Franklin in The New Yorker has noted how ‘Zoey flaps around, trying to please,’ while Melissa Maerz in the Los Angeles Times has called Wever’s Zoey ‘the eager puppy of a junior nurse who trails Edie Falco’s character’ and declared that ‘no one else can do the very slight, confused-cocker-spaniel head tilt like Wever’. Even Merritt Wever herself has chosen animal-related language when discussing the role, referring in an interview for season two to how Zoey is ‘chomping at the bit’ and that she ‘scurries’, and in an interview for Vulture further comments that Zoey ‘looks like the pink bunny’. Moreover, discursive attention has picked up on the importance of the use of costuming for the characterisation of Zoey, and the printed scrubs she wears in earlier seasons frequently feature animal-based imagery. Within the context of transmedia storytelling, Zoey’s ‘Nursing It Yo!’ blog on Tumblr also makes repeated references to animals. While the links between Wever’s Zoey and animals have been noted across a number of levels and discourses, what deserves to be unpicked in more detail is how this link informs Wever’s acting choices.

hopping like a kangaroo

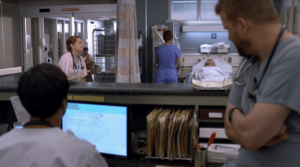

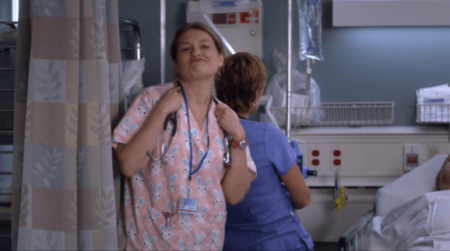

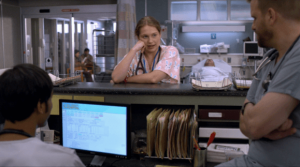

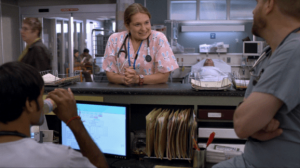

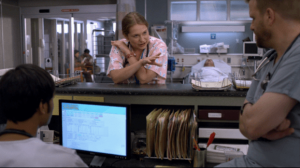

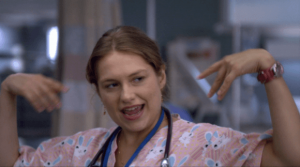

In ‘Game On’, approximately eleven minutes into the episode, Zoey, watched by Thor (Stephen Wallem) and Sam (Arjun Gupta) from the nurses’ station, repeatedly tries to approach Falco’s Jackie, keen to share news about her developing relationship with EMT Lenny (Lenny Jacobson). Dressed in rabbit-patterned scrubs, Wever here hops towards Falco with an upward bounce distinctly reminiscent of a kangaroo. (Similar to a children’s television theme tune or a home video clip show, the non-diegetic music used underlines the jerkiness of the quality of her movement and her youthfulness, as well as the light-heartedness of this moment.) After several false starts, she quickly ‘confesses’ that she has had sex with Lenny, which elicits a semi-feigned shudder and disapproval by her co-workers. She parries this response with the words ‘Y’all’s uptight!’, delivered with a Deep South accent and whilst grasping her stethoscope – here, her character effectively switches from a bunny-scrubbed kangaroo to a dungaree-clad redneck. She then approaches the station with a skip, and proceeds to talk about her sexual experiences with Lenny in a wistful tone. Wever controls the pacing of her vocal delivery very effectively, slowing down to the point where almost each word of her dialogue becomes a line in itself as her character describes herself as ‘smooth… like a gazelle. A very… satisfied, sexy gazelle.’ Throughout this moment, she makes noticeable use of her hands and fingers: she props her chin on her fist, clasps her hands, gesticulates, twirls her fingers and at the second mention of the word ‘gazelle’ strikes a pose reminiscent of antlers – here, she has her character mistakenly think that gazelles have antlers instead of horns. The scene comes to an end when Wever’s character turns and almost collides with hospital administrator Gloria Akalitus (Anna Deavere Smith), hiding her embarrassed face behind her hand. Only roughly 80 seconds in length, our outline here will hopefully convey that this is a dense, packed scene, in which Wever deals with several gear changes and different registers within which she is working, and one that involves several animals (kangaroo, gazelle, something antlered, as well as (via the costume) rabbit).

Within the context of acting, drawing inspiration from and making links to animals is certainly established within actor training, and related exercises can be found in many acting text books. As a representative example, James Penrod instructs the reader in his chapter titled ‘Developing the Role Through Movement’ as follows:

Another approach to characterization is to use animal imagery. While reading your playscript, think of an animal that might behave in a manner similar to that of your character. List words and phrases descriptive of that animal and how it moves. Some common phrases are: sly as a fox, slippery as an eel, sings like a bird, and struts like a bantam rooster. […] If you want to use the chicken as a point of departure for gestural and movement patterns, first try to mimic as precisely as possible the movements and apparent attitudes of the chicken, so as to get these rhythms “in your body.” Then you can try to simulate the hen’s movements as a human being might make them.’ (1974, 147-148)

Usually, such an approach is a step within the preparation and rehearsal process – ‘a useful “staging post” in the process of characterization’ (Ewan and Green 2015, 127) – one that can help actors develop their imagination, range of physical movements and engagement with their usual sensory perception. As Vanessa Ewan and Debbie Green have put it (using noticeably gendered language) in their movement handbook for actors:

The animal itself presents the actor with inspiring choices about the way a character operates in the world: the motivation for movement, the rhythm of life and the way it sees the world can all be taken into account. It may be that the actor can envisage an animal when he thinks of the movement of the character he is working on. Equally, he may know something of the character’s innate behaviour or personality and that, too, can inform his decision of which animal to choose to work with. A character develops through rehearsal. (2015, 159)

Of course, this methodological tool can and does also feature in finished performance, such as that by Merritt Wever in Nurse Jackie,[1] who gives what can be called an anthropomorphic performance. As Ewan and Green further note:

Anthropomorphism is normally thought of as giving an animal human characteristics. In this case, however, it is about creating a human character that develops from the study of an animal. For the actor, this is not some form of “cartooning” but […] derived from detailed study of a particular animal and taken into a fully-rounded human character with a complete inner landscape. (2015, 157–58)

getting ‘handsy’: Merritt Wever’s Zoey across the shot/reverse shot pattern

What is further noteworthy about Wever’s anthropomorphic performance is that it is systematic, both within our chosen scene and across the series: The extract from ‘Game On’ more explicitly articulates and brings to the foreground Wever’s linking to animals that already runs throughout the programme (as the quotations in our second paragraph attest). In our chosen scene, Wever employs physical movements reminiscent of animals in a way that establishes motivated patterns: with her bounce conveying her somewhat nervous excitement at sharing her big news and anticipating some pushback, Wever’s Zoey does not just hop towards Falco’s Jackie, but also places a little hop in her approach to the nurses’ station, indicating that her excited energy has not dissipated after her co-workers’ initial reaction. Similarly, just as she makes links between different moments within the scene through her hopping, she also does not arrive at the antler pose ‘out of nowhere’: here, the sensuous energy that animates her twirling movements carries forward, rendering the antler pose part of the organic trajectory of Wever’s use of her hands. Resisting the use of convenient one-offs, Wever locates her choices within systems across several cuts in the shot/reverse shot editing pattern.[2] One important further aspect of her systematicity is that Wever has the skill and confidence to place firm boundaries on her use of such animal-related and other attention-drawing physical movements: she here ends the scene with her hand on her chin, quietly watching and listening, and continues this in the follow-on scene. Indeed, the effectiveness of Wever’s systems partly depend on her often being still and not ‘doing (too) much’, which helps to make sure that her character does not tip over into caricature, rendering her ‘funny but not quite ridiculous.’ (Dolan 2013, 63)

Wever’s anthropomorphic approach also reflects how she controls her performance as Zoey by paying careful attention to and developing how she inhabits her body. Noticeably hyper and physically awkward in early seasons, Wever’s Zoey matures and grows in confidence, and her relationship with Lenny marks an important turning point in this development. Wever’s twirling of her hands and antler pose in this scene underline her character’s growing bodily confidence and enjoyment of her own sensuous physicality, and she is keen for he co-workers to know about her new relationship and sexual satisfaction. At the same time, with the look of uncertainty that flashes across her face the first time she refers to herself as a gazelle, the tempering of the ‘sexy gazelle’ with the bouncy kangaroo, the incorrect gestural invocation of antlers and the acute embarrassment in front of Akalitus, Wever subtly signals that Zoey has not fully arrived at this more confident, mature state yet, but finds herself at a point of transition and overlap. It is here important to note that the easy binary opposition between initial awkwardness and later mature confidence is challenged by Wever’s choices. She regularly shows her character’s enjoyment of inhabiting her body in earlier seasons (e.g. pushing herself on her castered chair, using a pedometer), and maintains some of her youthful awkwardness in later seasons (e.g. hobbling after strenuous biking). Paying careful attention to her character’s bodily inhabitation is clearly important to Wever on both a synchronic and diachronic level, and this has helped to invest her character with a particular sense of agency (see Dolan 2013).

Wever’s Zoey ends the scene ‘stifled away’ and spends the follow-on scene quietly observing

Concerned about the invisibility of gender criticism, Kim Akass has rightly noted that Nurse Jackie, which has not received the same level of attention and praise as some of its contemporaneous male-centric shows, such as Boardwalk Empire (HBO, 2010-2014), ‘treats its women as sentient beings’ (2012). This is partly achieved by Nurse Jackie’s evident investment in the acting by female actors. Merritt Wever clearly thrives in the culture of production enabled by Showtime – whose quality brand identity, as Subramanian (2012) has pointed out, features the female-centric, single-camera half-hour dramedy genre – and Liz Brixius and Linda Wallem, the two women who co-created (with Evan Dunsky) the series, and showran and executive produced (with Caryn Mandabach and John Melfi) its first four seasons. While Wever is often quick to acknowledge that ‘it was there in the writing’, she deserves more credit herself, especially given that the character of Zoey Barkow was initially written as a ‘bit stock’, relying on the trope of the young, eager intern. It is through the input of and approach by Wever, who trained in acting in New York after attending a performing arts high school (incidentally, the same as Jennifer Aniston), that Zoey Barkow developed into the character we see on screen. This input and approach involves trying out her own, unconventional ideas and the use of improvisation, as described by Liz Brixius: ‘Merritt will say every word you’ve written in the script, but then she’ll add something totally unexpected, like she’ll curtsy, or pat Jackie on the back, and everyone will just lose it[.]’ Wever has repeatedly expressed her appreciation of being given the space, time and opportunity to do this:

They [Linda Wallem and Liz Brixius] were really open to me playing around. I didn’t even realize how rare it was, and how much of a favor they were doing me. They let me try things and fail in an environment where I didn’t have to feel shame or embarrassment. It was okay if something didn’t work, and since it was okay, I could try something new the next time.

The writing, directing and acting on Nurse Jackie formed a productive symbiotic relationship, in which, according to Wever, Wallem and Brixius ‘did a really good job of responding to things that I did’, and according to Wallem, also at times left moments in the script ambiguous so that Wever could improvise. Too rare within the determinants of acting in the USA and elsewhere,[3] this kind of symbiotic relationship here in this scene results in Wever playing around with what could look on the scripted page as not very much and, more generally, in her using animal influences to enrich the portrayal of a character who is both synchronically and diachronically complex. Awkward and sensuous, confident and comfortable, wanting to be ‘part of the gang’ and firmly anchored within her moral compass, Merritt Wever’s Zoey in Nurse Jackie is the kind of well-rounded female character that Kim Akass (2012) and we can enjoy.

Gary Cassidy is currently undertaking AHRC-funded doctoral research at the University of Reading. His thesis explores the rehearsal process of playwright Anthony Neilson, using filmed footage of rehearsals and interviews. He trained as an actor at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama and has thirteen years of acting experience – Equity name Cas Harkins – covering film, theatre, television and radio. Plans for future research focus on using his research methodology to explore the working processes of other contemporary theatre practitioners.

Simone Knox is Lecturer in Film and Television at the University of Reading. Her research interests include the transnationalisation of film and television (including audio-visual translation), aesthetics and medium specificity (including convergence culture), and representations of the body. She sits on the board of editors for Critical Studies in Television and her publications include essays in Film Criticism, Journal of Popular Film and Television and New Review of Film and Television Studies.

References:

Akass, Kim. 2012. ‘Welcome Back HBO’. CSTOnline. Accessed 6 June 2015. https:///welcome-back-hbo-by-kim-akass/

Dolan, Jill. 2013. The Feminist Spectator in Action: Feminist Criticism for the Stage & Screen. New York; Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ewan, Vanessa, and Debbie Green. 2015. Actor Movement: Expression of the Physical Being – A Movement Handbook for Actors. London; New York: Bloomsbury.

Hewett, Richard. 2015. ‘The Changing Determinants of UK Television Acting’. Critical Studies in Television 10 (1): 73-90.

Pearson, Roberta. 2010. ‘The multiple determinants of television acting’. In Genre and performance: film and television, edited by Christine Cornea, 166-83. Manchester; New York: Manchester University Press.

Penrod, James. 1974. Movement for the Performing Artist. Palo Alto: National Press Books.

Subramanian, Janani. 2012. ‘Like Sands through the Half-Hourglass: Nurse Jackie and Temporal Disruption’. In Time in Television Narrative: Exploring Temporality in Twenty-First Century Programming, edited by Melissa Ames, 245-256. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Footnotes:

[1] This links to our previous work on Charles Dance and the Psychological Gesture.

[2] These systems are further connected by the re-appearance of the non-diegetic music after the first mention of the word ‘gazelle’.

[3] Wever’s own professional experience has instilled in her an awareness of how rare it is to be able to risk trying and failing: ‘[…] the more I work away from Nurse Jackie, the more I appreciate it. It is not like that everywhere, it really isn’t.’ This issue certainly deserves more consideration than we have scope to give to it here; see Pearson (2010) and Hewett (2015).