OLIVER: Can you imagine? Once upon a time, typewriters were made in Great Britain.

NORMA MOODY: Imagine typewriters.

Oliver’s Travels: Looking for Aristotle by Alan Plater

Those of you who have read some of my previous pre-Christmas offerings will be aware that one of the things that I associate with this time of year is the prospect of a new television soundtrack. But this year, I want to take a moment to reflect on the festive gift that probably was the most important item that I ever received in terms of writing about television and being able to connect with other people.

This was a Christmas gift from my wonderful, thoughtful parents in December 1977… and, really, this was the key that unlocked the door to the world of writing about television.

It’s difficult to describe now how massively important a piece of equipment this was in the pre-home Personal Computer age of the late 1970s and early 1980s, but to be able to quickly and clearly assemble thoughts and information and communicate them via fanzines or letters to like-minded people was the equivalent of being able to access the internet in so many ways.

For a start, I could go down to the local library, plough through the newspapers, come home, and – comparatively neatly – type up…

Yes, I know that this is the sort of information that you find on the internet – or maybe even in a book if you remember those – within seconds or a few minutes, but at the time to have a clear listing of data that could be filed and, if necessary, copied and shared with friends was a huge leap forward.

I had a wonderful English teacher, Miss Wright, who was also into science-fiction. And she encouraged me to write reviews… and to write into magazines. I got letters printed… and I heard back from other people around the world, most of whom also seemed to have typewriters, and also had bits of data of their own. And all of a sudden, all manner of typed lists of data and information on television programmes was arriving by air mail. Outlines of Quatermass and the Pit (1958-1959) were being sent to pen-friends in Miami, and details of different edits of The Prisoner (1967-1968) with weird sets of theme music were being received in return.

It’s so strange now – in a world where children key in what they want to discover into tablets while still in their playpens – to think that “typing” was a specialist skill. My typewriter came with me to university. As I recall, I was the only person on the course who had one, or who could type at any speed at all. That immediately gave me an edge in so many respects. Certainly, it cut down considerably on the costs of having important reports typed for presentation. Yes, ‘typing’ was a job when most people couldn’t or had no need to type… and a typist would turn their hand to taking illegible scrawl on any subject and making it look like a readable, professional document.

Of course, this came with issues – notably that of having a typist who was not familiar with the subject matter grappling with some of the quirks of a specialist area. “Surely mA and MA are the same thing?” they would ask. “Not really,” I’d need to explain, “One is a thousand million times bigger than the other and will fry the transistors even before you start…”

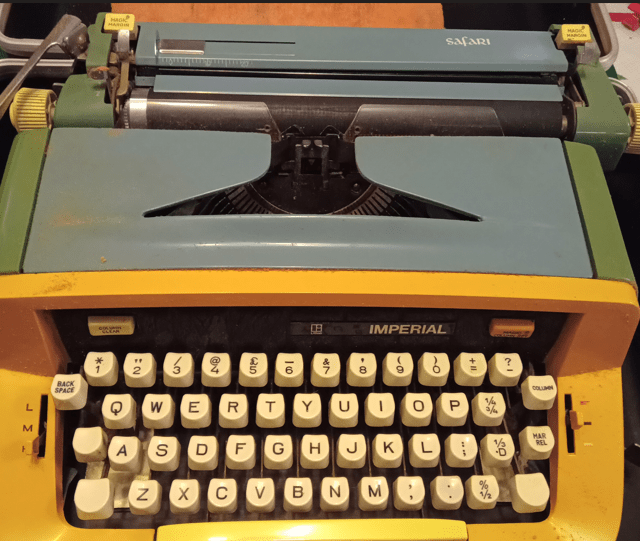

When we had team tasks in academia, I was the one who could offer a professional looking submission on behalf of the group. It would mean hammering away long hours – the Safari being an old-fashioned manual machine rather than offering electrically powered key-strokes – but compared to the hand-written offerings or those assembled by well-meaning pool typists, it gave us the edge. And, I hope, helped us to get those degrees and qualifications.

And when the Imperial Safari wasn’t being used for revision sheets or tutorial notes or for formatting research findings, it was, of course, being employed on more televisual related material. Fanzines – so much fun to do with your mates as you got to see all manner of material on videotape and then enthused about it in print to like-minded readers, who would in turn reflect your enthusiasm with theirs and send more missives of fascinating historical documentation or thoughts or memories… all presented via a typeface that you knew had been hammered into the paper with a passion.

In time, it wasn’t only fanzines, but also magazines. Properly printed, non-photocopied journals that you could go into WH Smith and find on the shelf… where you typed your article on the typewriter, sent it in on paper, and then they took it and retyped it or typeset it for dissemination out into the big wide world. And programme notes. Even back then when you couldn’t watch these programmes on shiny discs in the comfort of your own home, you could still take a bus and a train and the underground down to the National Film Theatre to watch exotic rarities of yesterday and have some accompanying contextual notes generated on – yes – a typewriter.

Of course, time moves on. The word processor arrived – and no longer did we have to think or write contiguously. Text and data were fluid. And by now, you didn’t have to hammer the keys quite so much and make so much noise. But the decade or so of knowing the force that needed to be applied to each and every stroke of the Safari is not a habit I’ve been able to shake. In the 1980s, the loud clack of a keyboard in academia was an advantageous skill. In the 2010s, it was merely something that upset the rest of the cohort and probably suggested that you shouldn’t have gone back to academia in the first place. And perhaps it was right and I should have listened to it rather sooner than I did…

I have been through many, many, many computers and laptops over the last 40 years or so. They have done their job and served their purpose in getting that magazine article crafted or that soundtrack spreadsheet assembled… and then they have been wiped, cleaned, dismantled and disposed of. But the Imperial Safari is still here – within sight of the desk that I work at even now.

It may not go on-line, but it’s the device that really opened up the world to me… and led me to so much fun and so many friends and so many opportunities.

Thanks Mum. Thanks Dad. Happy Christmas.

Andrew Pixley is a retired data developer. For the last 30 years he’s written about almost anything to do with television if people will pay him – and occasionally when they won’t. He hopes that everyone reading and contributing to CSTonline will be able to spend the holiday season with those who mean the most to them, and doing all the things that they enjoy sharing together. And he feels very lucky that he’s been able to do that himself for so many years.