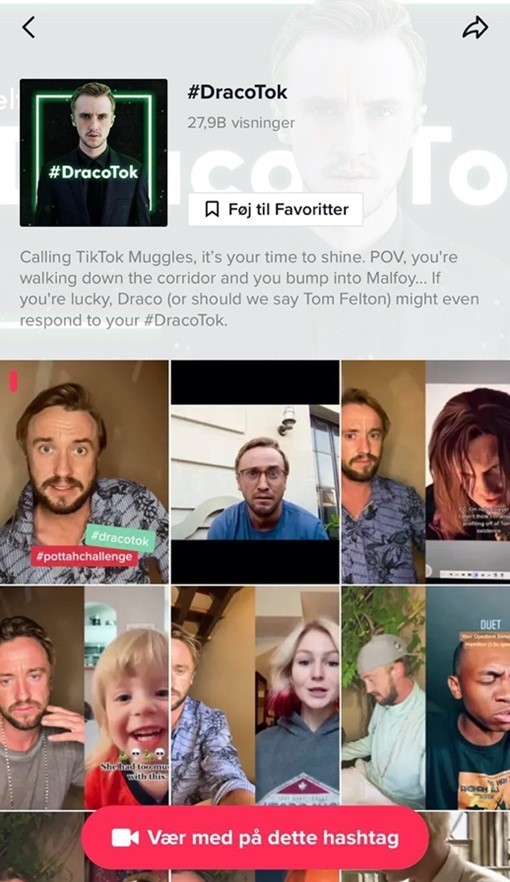

Working with TikTok daily as part of my PhD project – and being a heavy user myself – I am very aware of the constant changes happening on the app with new trends and memes appearing every week. What fills up your algorithmically driven For You Page[1] one day, might have changed into something completely different the next day (Anderson, 2020, p. 5). Everything moves incredibly fast on TikTok, which is partly due to the extremely short-form video content – typically a TikTok is well under 60 seconds long. To keep pace with the nature of the app, TikTokers need to be able to create content quickly and on a whim. This results in content often seeming spontaneous, e.g., the location being the creator’s car parked at a grocery store, and ‘giving off’ a very authentic and relatable vibe. Adding to that, TikTok also works as a creative platform for creating the actual content (Bresnick, 2019, p. 9-10). Through the app, users can record videos and easily add different effects and filters, edit, add text, and do whatever else is needed to make the desired video (Miltsov, 2022, p. 2). This makes it incredibly accessible for users of all ages and with different levels of technical knowledge to create content.

Fig. 1: Examples of how content can look on TikTok posted by @colbyandtoast, @taylorswift and @mikaelarellano (2022).

With this being TikTok’s digital environment, I was quite surprised when I found out that more and more professional producers of fiction are creating fictional series exclusively for TikTok. I started looking into this when the Reaching Young Audiences research project asked me if I knew anything specifically about fiction on TikTok. To be honest, my knowledge about this was quite limited at the time. Eventually I found out that fiction on TikTok comes in many different variations, including, but not limited to, user-created fanfiction, fictional TikTokers and well produced narrative web series. In this blog post, I present some of the different fictional formats I have come across on TikTok – fanfiction, fictional influencers and fiction series made specifically for TikTok. The first one being the most ‘TikTok native’ of them, as it is user-created fiction.

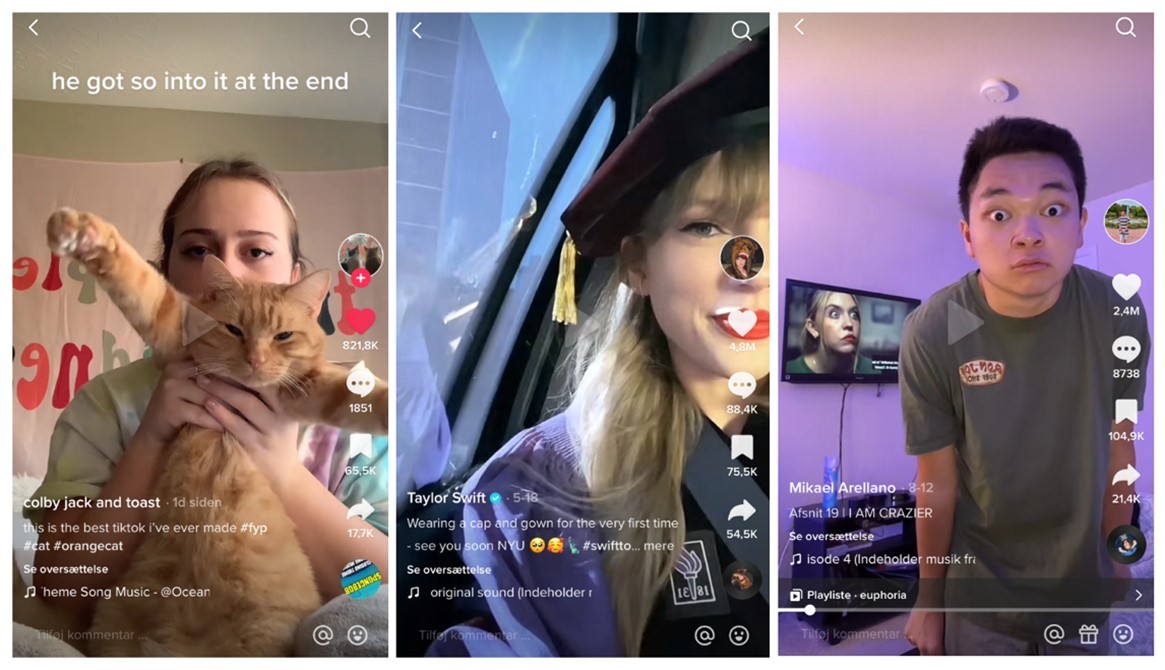

When #DracoTok took over TikTok

TikTok rose to popularity in 2020 when most of us was stuck at home due to the COVID-19 lockdowns around the world, looking for interesting (and comforting) content and new ways to stay in touch with the world (Redvall, 2020). During this period, many users on TikTok expressed how they were rediscovering nostalgic content from their childhood or teenage years. This could be rereading books, rewatching movies or in other ways reconnecting with fictional universes or fandoms that used to be a significant part of their lives. For example, a lot of users heavily reconnected with the wizarding world of Harry Potter (Tanatarova, 2020). The trending hashtag “#DracoTok” exploded in September 2020 and quickly developed into a subcommunity of fanfiction on TikTok. The “Draco” in #DracoTok refers to the character Draco Malfoy who is portrayed as a snobbish and mean bully with Voldemort supporting parents in the Harry Potter books and movies. Videos using the hashtag collectively now have more than 27,9 billion views and the trend also has its own official page on TikTok.

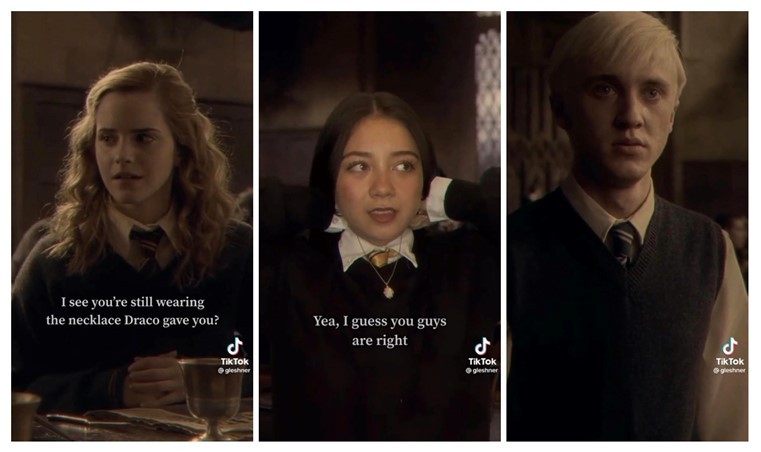

As shown on the screenshot, Tom Felton, who played Draco Malfoy in the movies, started to interact with and react to some of the #DracoTok content which of course made the trend even more popular. One of the most prominent types of #DracoTok videos is the so-called point of view (POV) video (ibid.). In a POV video users digitally insert themselves into the fictional universe and in some way involve themselves in an often romantic scenario or conversation with one or more characters.

In that way, the users create their own fiction through a continuation of the already written story by for example adding themselves into the narrative and giving an already existing character new character traits. The popular trend expanded into being created with multiple Harry Potter characters and showing scenarios “ranging from love triangles, Amortentia potions and sneaking around after hours” (ibid.).

Fig. 3: Screenshots from POV video by the user @gleshner (2022) showing the character Hermione Granger (Emma Watson), @gleshner herself and the character Draco Malfoy (Tom Felton).

This POV video by the user @gleshner has almost 800.000 likes and over 10.000 comments. In this example, @glesner inserts herself into the universe and creates a new storyline about her relationship with Draco. This is done through her editing of the original clips and by adding new lines (the text in the video).

Moving on from purely user-generated fiction to a more hybrid format, I now want to introduce the interesting phenomenon of fictional influencers – or in this case fictional TikTokers.

“A scripted coming of age story”

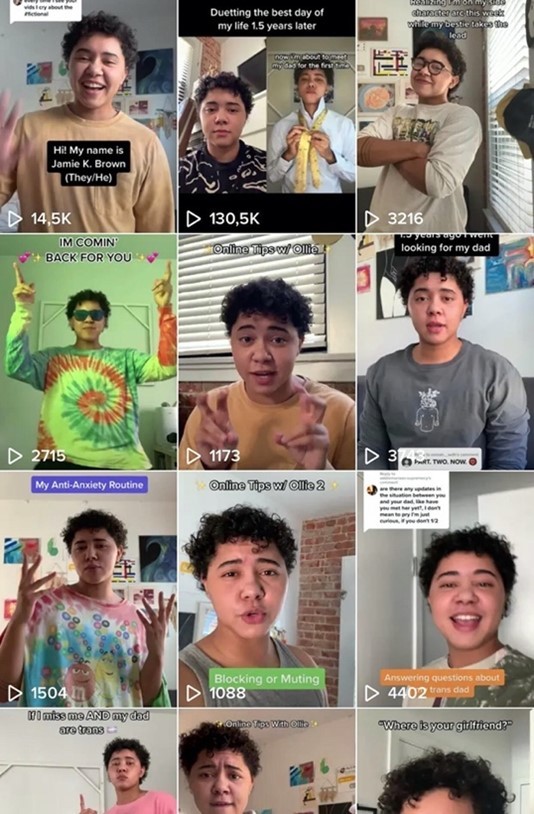

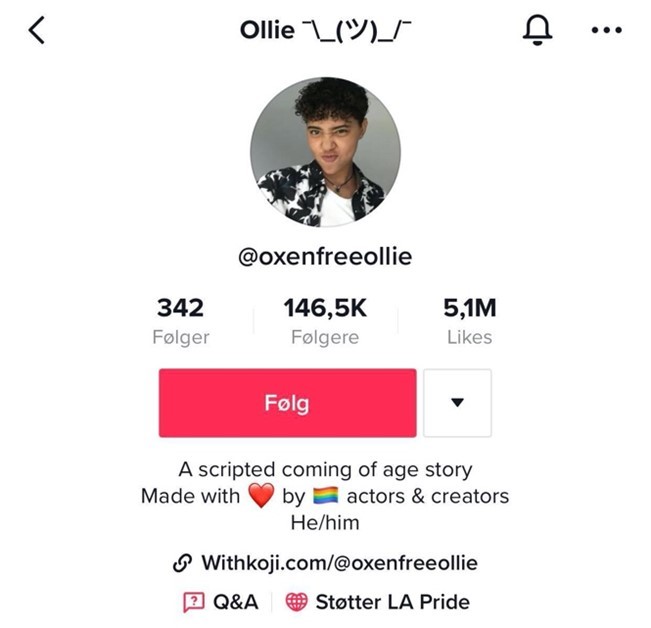

At first sight Ollie’s (@oxenfreeollie, 2022) profile looks very similar to those of many other young TikTokers. He talks about topics such as his struggles with mental health and being part of the LGBTQ+ community, while also using trending memes and sounds.

But Ollie is not a real person. He is a character created by the company FourFront and an example of what they call “character-driven TikTok entertainment” (Haasch, 2021). Ollie’s completely fictional story is being produced by FourFront in collaboration with the actor Jamie K. Brown who plays Ollie. Ollie posts content just like any other TikToker and regularly interacts with some of his almost 150.000 followers in the comment section. FourFront describes this phenomenon as an “evolution of motion pictures into living pictures (…) Stories that feel alive and live beyond your screen” (ibid.). Ollie is just one of over 20 fictional influencers created by FourFront who wish to profit on this through e.g., brand deals or online events with the fictional characters (ibid.). On Ollie’s profile it is clearly stated that this is “A scripted coming of age story”:

Fig. 5: Ollie’s (@oxenfreeollie, 2022) bio on TikTok where it is stated that his story is fictional and created by LGBTQ+ people.

Despite the transparency, it becomes clear in the comment section of a recent video from early November (where Jamie K. Brown ‘reveals’ himself) that not all of Ollie’s followers had realized the fictional aspect of the profile. One user writes: “What? I was so invested, I feel robbed.” Another simply asks: “WAIT IT WAS FICTIONAL!?!?” (@oxenfreeollie, 2022). FourFront had previously stated that they want the audience to know that the stories are fictional, and that they would like to work with TikTok on how to make this clearer on the app (Haasch, 2021). However, judging by the comments from Ollie’s followers it seems as though the fictional aspect could have been made clearer.

The last fictional format I want to introduce is a variation of something we all know – TV drama series. The first TikTok fiction series was created in Australia in 2020, whereas the latest one (that I know of) is NRK’s (Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation) Toxic, which premiered earlier this November.

The world’s first TikTok series Love Songs

The Australian series Love Songs claims to be the world’s first narrative series produced exclusively for TikTok (Love Songs website, 2022). The first episode aired in February 2020, and the series (created by Hayley Adams and Michelle Melky) now consists of two seasons with 20 episodes each, the duration of an episode being about one minute.

Fig. 6: This is what the world’s first TikTok series Love Songs looks like (@lovesongsseries, 2022).

Love Songs is described as “an innovative vertical storytelling series that follows the relationships of Gen Z’s navigating the ups and downs of their dating lives” (Tinder Newsroom, 2021). The focus on dating is further emphasized in the making of season 2, as the season is created in partnership with the world-famous dating app Tinder. Love Songs has over 20 million views, 140,000 followers and 2.8 million likes on TikTok (Love Songs webside, 2022). Only a year after the release of Love Songs, three new Australian TikTok series were released. The success of Love Songs played a part in at least one of these instances, as the series Scattered is also created by Hayley Adams and Michelle Melky. Below I have made an overview of the eight TikTok series I have come across during my initial research into this topic, including when they were released and where they originated.

Fig. 7: The figure shows the eight TikTok fiction series I have come across during my initial research into fictional content on TikTok.

NRK is joining the trend with the new series Toxic

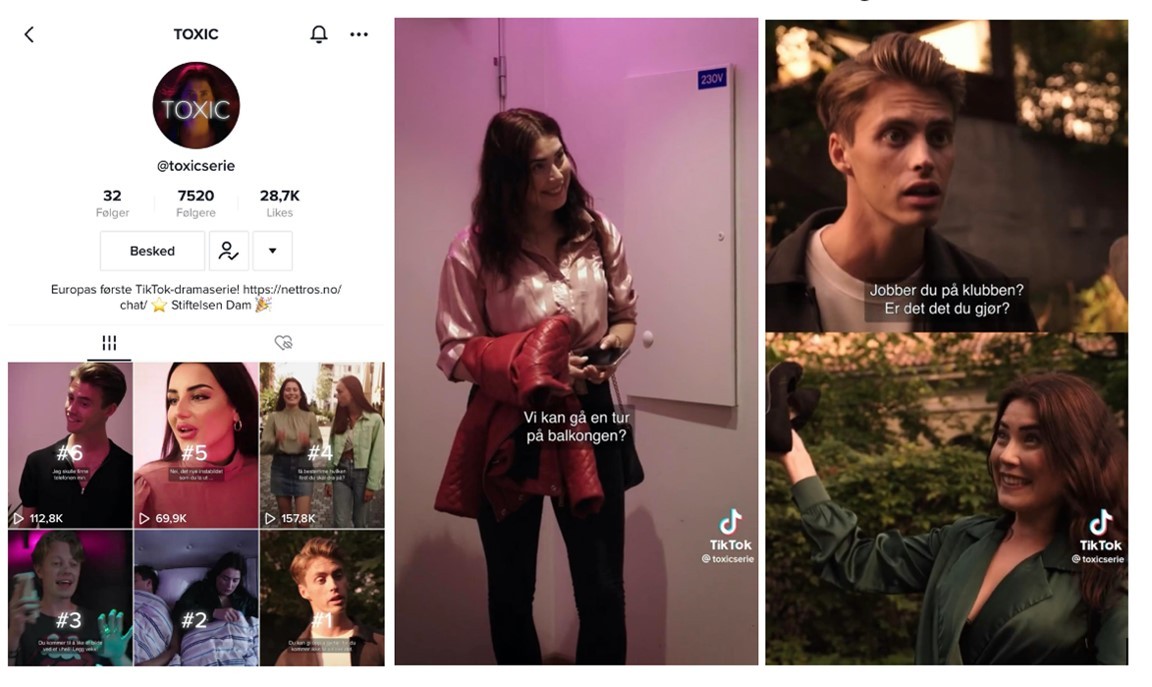

On the 10th of November, the Norwegian public service broadcaster NRK aired the first episode of their new TikTok series Toxic. So far, the episode has over 380,000 views, and the @toxicserie profile have almost 30,000 likes and 7,619 followers (@toxicserie, 2022). A new episode has aired every or every other day since the series launched. 28-year-old Aleksander Dokkeberg is the director behind the series which has a main target group of 13-25-year-olds (Klevjer, 2022). Dokkeberg has previously directed the series Flink, the first two seasons airing on YouTube, while the third season aired on TikTok earlier this year. Toxic is a love story between the nightclub owner Aurora and the TikTok star Chris, but mental health and eating disorders are also central themes in the series (ibid.). Toxic has received 2.2 million NOK in funding from The Dam Foundation and the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services (ibid.).

The character Chris is played by Leif Kokvoll, who also happens to be a TikTok star in real life, just like multiple of the other actors. Director Aleksander Dokkeberg states that he liked the idea of creating a universe around the TikTok platform: “Not only can the audience meet our characters in the series, but also see faces and personalities they recognize from the same platform” (ibid., my translation from Norwegian). Every scene in Toxic has been filmed twice, in the traditional horizontal format for YouTube as well as in the vertical TikTok-adjusted format.

‘TikTok-ified’ fiction for Gen Z

Common for the different TikTok series is that they have all been created to fit TikTok’s premises. Most obvious is the ultra-short episode length, typically 1-2 minutes, and the vertical format, which are significantly different than what most creators are used to when making fiction for TV or streaming. Besides this, it is clear that Gen Z is the desired target group for the majority of these TikTok series. Firstly, this generation is very present on TikTok, making the platform a great fit in terms of reaching them. Secondly, the actors in several of the series are TikTokers in real life, and therefore already have a following on the app, which makes them well known by large numbers of the potential audience, as is the case with Love Songs and Toxic (Tinder Newsroom, 2021; Klevjer, 2022).

Thirdly, the choice of themes and characters also seem to have been carefully chosen with Gen Z in mind. Several of the series focus on mental illnesses or other stigmatized themes, while LGBTQ+ characters, sexuality, and gender fluidity are also central aspects in multiple of the series, for example Australian series Scattered and The Formal. This is not so unusual when thinking about some of the most popular teen and youth streaming series from the last couple of years. Netflix series such as Heartstopper, Young Royals, Heartbreak High or Sex Education all deal with similar themes and introduces a wide and diversified character catalog.

Having just started to research this, I look very much forward to seeing how TikTok fiction develops over time and find out whether this kind of content may become as popular as their longer and horizontal counterparts from Netflix. I can only encourage others to explore the innovative and wondrous world of fictional content on TikTok; You only have to binge about 30 minutes to catch up with an entire season, so there really is no excuse not to do so.

Amanda Skovsager Mouritsen is a PhD student at the department of Media and Journalism Studies at Aarhus University. In her PhD project, she investigates TikTok content, experience and use among adolescents and young adults in Denmark. Since April 2021 Amanda has been a research assistant in the Reaching Young Audiences: Serial Fiction and Cross-Media Story Worlds for Children and Young Audiences research project.

Footnotes

[1] The For You Page (FYP) is the algorithmically driven ‘front page’ on TikTok. Most users predominantly watch content through this.

References

Anderson, K.E. (2020). “Getting acquainted with social networks and apps: it is time to talk about TikTok”. In Library Hi Tech News, 37(4). doi: 10.1108/LHTN-01-2020-0001

Bresnick, E. (2019), “Intensified Play: Cinematic study of TikTok mobile app”. In Research Gate. https://researchgate.net/publication/335570557_Intensified_Play_Cinematic_study_of_TikTok_mobile_app

Haasch, P. (2021, October 12). “Your favorite TikTok influencer might be fictional” [web article]. Insider. https://insider.com/fictional-tiktok-characters-fourfront-influencers-2021-10

Klevjer, C. A. (2022, September 16). “Norges første dramaserie på TikTok” [web article]. NRK. https://nrk.no/kultur/filmskaper-lager-serie-til-tiktok-1.16068390

Love Songs website (2022). https://lovesongsseries.com

Miltsov, A. (2022). “Researching TikTok: Themes, methods, and future directions”. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods, 2nd Edition, edited by A. Quan-Hasse, and L. Sloan. SAGE. doi: 10.4135/9781529782943.n46

Revall, E. V. (2020, April 17). “Family Binge-watching in Times of Corona” [blog post]. https:///family-binge-watching-in-times-of-corona/

Tanatarova, E. (2020, September 22). “TikTok is reclaiming Harry Potter because JK Rowling ruined it” [web article]. i-D. https://i-d.vice.com/en/article/ep43nk/tiktok-harry-potter-jk-rowling-transphobia-draco

Tinder Newsroom (2022, May 3). “Tinder dedicates “Love Songs” – Australia’s first TikTok narrative series to Gen Z” [web article]. Tinder webpage. https://au.tinderpressroom.com/lovesongsseasontwo

TikTok profiles

@colbyandtoast (2022): https://tiktok.com/@colbyandtoast

@flinkserie (2022): https://tiktok.com/@flinkserie

@gleshner (2022): https://tiktok.com/@gleshner

@ghytv_romance (Goddess Hotel) (2022): https://tiktok.com/@ghytv_romance

@lovesongsseries (2022): https://tiktok.com/@lovesongsseries

@matchedtheseries (2022): https://tiktok.com/@matchedtheseries

@mikaelarellano (2022): https://tiktok.com/@mikaelarellano

@oxenfreeollie (2022): https://tiktok.com/@oxenfreeollie

@scatteredseries (2022): https://tiktok.com/@scatteredseries

@taylorswift (2022): https://tiktok.com/@taylorswift

@theformalseries (2022): https://tiktok.com/@theformalseries

@toxicserie (2022): https://tiktok.com/@toxicserie

@trap_official (2022): https://tiktok.com/@trap_official