In the Summer of 1994, it became legal for shops to open on Sundays. Until then, the British Sunday could be a dreary affair because shops were closed, as were all cinemas, pubs and other places of entertainment. The comedian Tony Hancock made tragi-comedy out of this in his “Sunday afternoon at home” radio episode of 1958, for example. But one thing people could do was watch TV, and I have been looking through some daytime schedules from long ago because I was tracking down TV programmes about the dramatists Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter for a research project. It turned out that back in 1966, for example, you could watch ITV on a Sunday and find out how to play better golf, speak Russian, lay a garden patio or learn about the Theatre of the Absurd, and all before teatime.

As it still is, the ITV channel was charged with doing Public Service Broadcasting and from its inception in 1955 it had innovated in educational TV as well as in entertainment programmes. In prime-time, ITV relied on imported American thrillers and Westerns, genres with plenty of action and fast-moving storylines, as well as offering British-made programmes in popular genres like the hospital drama Emergency Ward 10 (1957-67), the live variety (vaudeville) spectacular Sunday Night at the London Palladium (1955-67) and the game show Take Your Pick (1955-68), for example. However, companies holding ITV franchises also had to demonstrate their success at fulfilling their public service remit in order to have their lucrative contracts renewed. The Pilkington Report (1962), an inquiry ordered by the British Government into ITV’s performance, critiqued the channel for the downmarket programming that it used to attract large audiences for its advertisers. Making serious programmes was a means to counter these criticisms, enabling ITV to assert its cultural credentials.

It was recognized that adults had spiritual and cultural needs after the years of their formal education. These needs could be served by programmes on Sundays about health, social issues, cooking, sport, home improvement, literature or drama, for example. But there were bound to be tensions between education, information and entertainment, and programme makers were concerned to avoid condescension, over-simplification and dullness. Even so, television could broaden viewers’ cultural horizons and deepen their knowledge. Elite expertise could be made available to everyone, and despite the implicit paternalism of this view it gave rise to ambitious and distinctive programmes.

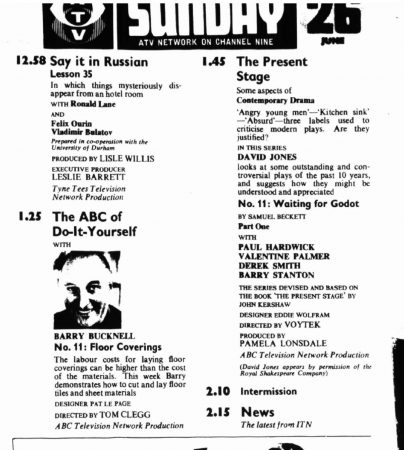

In the summer of 1966, the World Cup took place across much of July but there were no games on Sundays. Warm weather meant that activities like gardening, visiting parks and meeting friends competed with Sunday daytime programmes for potential viewers’ attention. However, because shops, cinemas, theatres and restaurants were all closed, enforced relaxation created opportunities for familial bonding, leisure pursuits and hobbies. Sunday daytime was a neglected part of the schedule in which a varied and interesting miscellany of content appeared. On ITV, programmes began with a church service at 11.00, followed by two programmes aiming to help viewers learn French and Russian. This instructional tone continued, but now more befitting the increasing prosperity of the period, with The ABC of Do It Yourself in which skilled handyman Barry Bucknell showed viewers how to do home improvements. Bucknell began the series by introducing viewers to the range of basic tools that the home handymen might require. Then in each episode, he addressed a common DIY challenge, such as electrical repairs, painting and decorating, hanging wallpaper and laying linoleum flooring. Bucknell himself demonstrated each task, talking about the job as he carried it out, with the studio cameras providing close-ups of particular details.

After Bucknell, ITV screened The Present Stage, a series about contemporary theatre, and it was this that drew my attention to ITV’s Sunday 1966 schedule in the first place. The series was made by ATV, the franchise holder now perhaps best known for the spy-adventure series The Avengers (1961-9) and the talent show Opportunity Knocks (1964-8). The plays featured in The Present Stage had been landmarks of British theatre in the preceding decade, and had been published in inexpensive paperback editions. The series featured two epsodes each about Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, Arnold Wesker’s Roots, The Fire Raisers by Max Frisch, The Bald Prima Donna by Eugene Ionesco and Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker. These plays had made a public impact, reviewed in newspapers and produced by amateur theatre groups; they were “modern classics”.

The TV Times listings magazine ran a feature announcing the series, asking “Do you really enjoy the modern play like Look Back in Anger or Waiting for Godot?” The implied answer was no, and the series was promoted as a means for viewers to access material that was off-putting or even incomprehensible. John Kershaw, the series’ creator, commented: “I am hoping that this series will make modern drama interesting to people who perhaps never get the chance to go to the theatre.” There was discussion of the plays’ themes and dramatic techniques, with extracts staged in the studio by a team of experienced actors. ITV viewers learned about Waiting for Godot at lunchtime on 26 June 1966, perhaps with their meat and two veg, after Bucknell’s DIY episode about different kinds of floor covering including linoleum and vinyl tiles, and a demonstration of laying carpet. Viewers might have chosen to watch the competing programme on BBC1 at that time (there was no BBC2 on Sunday daytimes then), but the rival channel’s Gardening Club with advice about growing tomatoes, followed by an episode of Farming about beef production in Yugoslavia, probably did not present a serious challenge to The Present Stage.

What should we make of this odd corner of broadcasting history? I think ITV’s Sunday daytime schedule was not only a cynical way to comply with regulatory demands for serious – meaning unpopular – programming. There were cheaper and easier ways of doing that. In my view, ITV was also aiming to generate inspiration, relevance and engagement. The value of both The ABC of Do It Yourself and The Present Stage was to inform the viewer about how the structure and components of a kitchen tap or Waiting for Godot worked in a practical context. It meant taking the play or the domestic appliance apart to see how it worked, then putting it back together. And moreover, it meant learning to exercise taste, how to appreciate design and style, and how to take part in a culture that might initially seem alien or forbidding. With Kershaw or Bucknell as their guides, ITV viewers in 1966 were offered access to activities and experiences that were hitherto barred to them. Analyzing a contemporary play and removing outdated Victorian features to install modern panelling were more comparable than they appear, because they were aspirational. It seems patronising to us now, but watching ITV might have been a better way of spending a Sunday than going shopping.

Jonathan Bignell is Professor of Television and Film at the University of Reading. He works on histories of television drama, cinema and children’s media, and on the AHRC research project ‘Pinter Histories & Legacies’ with colleagues at Reading, Leeds and Birmingham universities. Some of his work is available free online from his university web page or from his academia.edu page. A longer and more scholarly analysis of material in this blog will appear as J. Bignell, ‘“Do You Really Enjoy the Modern Play?”: Beckett on Commercial Television’, a chapter in David Pattie & Paul Stewart (eds), Pop Beckett (Hannover: Ibidem Books).