On May 30thTwitter and the BBC announced a live streaming partnership to provide coverage for a number of election related broadcasts including the May 31st BBC election debate and the June 8th Election Night Special. These election events were simulcast on BBC television. Unlike the television broadcast, the Twitter live stream occurred on an interactive platform with user comments occupying around half of the screen space. The live video stream was available outside of the UK and enabled national and international users to contribute to the overall election narratives.The BBC deal with Twitter represented a further move by the former towards online live video news and, given the number of other broadcasters that have made similar moves, we will possibly see even more broadcasters follow suit.

This new venture with Twitter follows BBC’s use of the Facebook platform for live video of events ranging from parliamentary debates to Facebook Live reports of protests and responses to major political events. As with its video on Twitter, BBC’s Facebook Live videos are accompanied by real-time user comments. In addition, users can indicate ‘reactions’ by using an emoji that flows across the video in real time. On both the Twitter and Facebook platforms, then, the BBC shares some of its editorial authority with users who may engage with the content in expected or unexpected ways. Given that these social media platforms allow for little real time moderation this imposes a certain amount of risk on the integrity of the live stream and the ultimate narrative that transpires through the amalgamation of video and user commentary.

The BBC is, of course, not the only broadcaster to produce live video for and distribute via a social media platform. Other broadcasters like Channel 4, Sky News and CNN have provided increasing amounts of news and entertainment coverage on these platforms. Equally, publishers like The Guardian and The New York Times and digitally born news and entertainment providers like Vice and BuzzFeed have, in many ways, been more assertive in their engagement with live video. Broadcasters, however, come to these platforms with slightly different challenges. These include the necessity to develop new forms of video or to adjust to the live streaming demands of social media platforms as well as devolving some of the authorship of the content to viewers and users. [i] This transition, although currently underway, has resulted in a somewhat peculiar form of news video; one where historically ‘paternalistic’ and authoritative broadcasts now depend upon but also compete with user and viewer input.

One notorious case that exemplifies the challenges for broadcasts in using live video is that of Channel 4’s live stream of the battle for Mosul in October 2016. The criticism of the live stream by Channel 4 was not so much related to what was contained within the streamed frame but the way in which it sat on the platform and solicited feedback and ‘reactions’ from viewers. These reactions, emojis, that allow users to express that they ‘like,’ are ‘sad’ or ‘angry,’ or are ‘wowed’ by the video, roll across the video as it streams in real time adding a form of viewer commentary to the events on the video screen. The dominant criticism levelled at Channel 4’s video stream was that it turned an on-going battle into a form of entertainment and that the reactions trivialized a very serious event by gamifying the conflict. This criticism came from both users commenting on the live stream as it occurred and from journalists and news organisations in the days following the battle (see Fig. 2)

Channel 4’s reaction to the criticism was to defend the live stream, indicating that it had an editor present to make any necessary judgement calls in the event of inappropriate material contained within the video. However, it was a relative dismissal of the concerns about reactions, instead claiming that this was a feature of Facebook Live video that the broadcaster had no control over. This is suggestive of one of the key issues with broadcasters’ use of such platforms. While Channel 4 may apply “the broadcaster’s remit to all content published online,” it defers responsibility for the contextualisation of that content to the platform and the users. Ben de Pear, Channel 4 News editor, has since suggested that lessons have been learned from the Mosul controversy. “It was a really stupid thing for us to do…We thought you can probably go live from almost anywhere…But, of course, we forgot about the bloody emojis, which were hearts and happy faces and smiley faces coming out when you’ve had Isis going on. It was not good.”

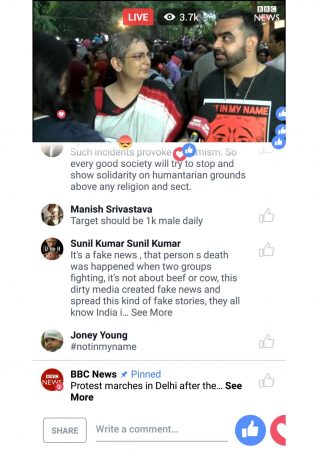

The case of the Mosul live stream indicates one of the main challenges faced by broadcasters like Channel 4 and BBC. They may be eager to engage audiences in innovative ways but they risk doing so in ways that they have little editorial control over. As Nielsen and Ganter suggest, legacy news agencies fear missing out on the opportunities offered by platforms and feel pressured by the successes of digitally born media organisations in these spheres (2017). They therefore take risks in experimenting with social media live video as demonstrated with Channel 4’s Mosul live stream. Elsewhere Kalogeropoulos and Nielsen’s study of online video news notes that the use of social media platforms by news organisations is prompted by a perception that audiences demand more video and that social media platforms are best situated to engage audiences with it (2017). In this sense it may be the case that concerns about the numbers of viewers and audience reach take precedent over the ways in which live video is experienced. For example, on a June 28th BBC Facebook Live video of protest marches held in Delhi comments ranged from those supportive of the protest to those that criticised the BBC’s bias, proposed the report to be fake news or were generally xenophobic in tone (Fig 3 and Fig 4).

While the content of the video provides background information on the formation of the protests, which were prompted by the murder of a Muslim teenager accused of having beef, the viewer reactions and comments provide an additional source of information sometimes steering the focus from the video towards unrelated issues, towards the BBC itself or towards other points of view. In one sense, this could be understood to enact a form of engaged citizenship whereby users and viewers intervene “in real time to shape the narrative frames” (Vaccari et al, 2015: 1043). Yet the lack of any real time moderation of such reactions and comments often results in a participatory mobocracy whereby those reacting and commenting are not held to the same journalistic and editorial standards as the BBC. Among the comments posted during the introduction of the live video were: ‘all religion is cancer,’ ‘BBC loves to twist the news just to cause disharmony in the world. Typical British trick,’ ‘Fake news,’ ‘Delhi is smelhi,’ ‘Notice how nobody protests the deaths of the LGBT in countries like Iran & Saudi,’ and‘What about the 10,000 people attending protest marches in London over the weekend. No BBC coverage whatsoever. BBC you should be ashamed of yourselves.’ Given that the live video report champions social media as a useful tool in the organisation of protest, it is strange to see the very same tool seemingly undermining this message by displaying a disorganised and erratic narrative alongside this report. And, unlike other online news containing pre-recorded images or articles which leave comments and reactions outside of the frame of the BBC content, the live streams are part of an unfolding and relatively uncontrollable narrative.

The BBC Twitter live stream of the debates and the election were somewhat different in that the video window was free from any viewer input. Yet on the left side of the BBC News Channel Twitter page comments that related to the election coverage and the elections more generally appeared in real time. On this platform, the presentation was somewhat more formal than one sees on Facebook Live video. Nonetheless, opportunities were taken by users to intervene in the interpretation of the video content (see Fig. 5) and this was available to all viewers of the platform.

Broadcasters’ foray into social media live streaming remains experimental and they are quickly adapting to the particularities of social video and changing their content to the demands of the platforms. However, questions of editorial responsibility will likely need to be addressed. In the context of social media live video streams, this responsibility is not held by any one party. The broadcaster, the platform and the user all engage in the delivery of the overall content which includes not only the video (provided by the broadcaster) but the platform’s tools (the capacity to react and comment) and the users (who provide the tone and themes of reactions and comments). Ultimately, it will likely require more work on the part of broadcasters and platforms, and more consideration of the form and function of each, to resolve these issues and develop both forms and platforms that can accommodate online live video news in a socially responsible and ethical way.

Works cited:

Kalogeropoulos, Antonio and Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis. 2017. ‘Investing in Online Video News: A cross-national analysis of news organizations’ enterprising approach to digital media.’Journalism Studies. June 13 2017 Online First Edition. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1331709 [Accessed on June 30 2017]

Nielsen, Rasmus Klein and Ganter, Sarah Anne. 2017. ‘Dealing with digital intermediaries: A case study of the relations between publishers and platforms.’ New Media & Society. April 17 Online First Edition. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/eprint/dxNzFHygAIRHviKP9MFg/full [Accessed on June 30 2017]

Vaccari, Cristian; Chadwick, Andrew and Ben O’Loughlin. 2015. ‘Dual Screening the Political: Media Events, Social Media, and Citizen Engagement. Journal of Communication. 65. 1041-1061.

[i]While I refer to those who comment as ‘users,’ their practice and engagement might also reflect certain aspects of ‘produsage’ (Bruns, 2016), co-creation, participation and ‘prosumption’ (Toffler, 1980). On Facebook Live videos users may opt to view, react or comment and, as such, various degrees of engagement are facilitated.

Sarah Arnold is Lecturer in Gender & Production Studies at Maynooth University. She is preparing the book Television, Technology and Gender: New Platforms and New Audiences. Her previous books include Maternal Horror Film: Melodrama and Motherhood and the co-authored Film Handbook. Her research focuses on viewing spaces and environments of television and film, particularly in the context of gender and emergent technologies. She is a regular contributor to the Critical Studies in Television blog.