Thinking the other week about binge watching – which, you may recall, I and my friends actually invented a few decades back – I have to admit that there were certain instances where it wasn’t actually our obsessional thirst for monsters and spaceships which turned us into televisual gluttons, consuming more than our body weight in Sapphire & Steel (1979-1982) episodes at a single sitting. In fact, it was what we were meant to do… persuaded to do. And in some cases, didn’t even realise we were doing it…

Back in the early 1980s when the universe was less than its present size, we had the modern miracle of home video. You could record from television – providing you weren’t going to charge people to watch it back – or you could purchase or hire pre-recorded tapes. Mainly of movies. After all, who would pay money to buy a tape containing a mere television programme?

Of course, television had made the jump to film. There has been big-screen adaptations of small screen brands ranging from a highly effective version of Quatermass and the Pit (1967) to a hideously contrived Are You Being Served? (1977) which seemed to totally ignore the comedic gold of character conflict between those confined in the workplace. Aside from wasting everyone’s time with these blogs each week, another notable slice of the guilt which I wake to every morning is that I’m one unit of the statistic that made On the Buses the biggest UK box office earner of 1971. What can I say in my defence? I had yet to make it into double figures in terms of age and I just thought that a bus driver and his conductor doing silly things to annoy their boss was sort of amusing.

But sometimes, just sometimes, you could buy a video cassette not of an established blockbuster, but of actual television shows. And the last thing that the publishers of these things wanted was to make you feel like you’d just shelled out £29.99 for some stuff you’d just seen and recorded off the television onto a blank tape which had probably cost you only £19.99 and which ran for far longer.

No – if these video entrepreneurs were going to charge you almost the equivalent of the annual colour TV licence for a piece of ferric tape which ran a mere 90 minutes, it was important that they bigged it up. These labels needed you to feel like this was a special experience! You weren’t watching television – you were going to the movies!

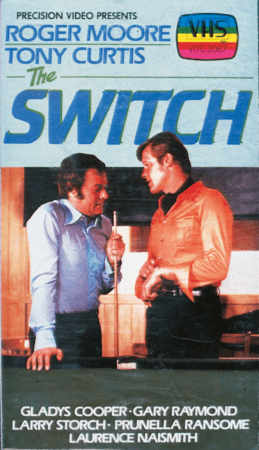

So, when you handed over hard cash at Boots or WH Smith for The Switch (1976) starring Roger Moore and Tony Curtis… hoping for a totally new slice of action from The Persuaders! (1971-1972) because that episode which ITV networked in Best of British had reminded you how good it was and you’d never known that there was a movie of it, you might have been a bit miffed to get home, insert said cassette into your new-fangled player and discover that you’d simply bought a 97 minute compilation assembled for the Italian market by splicing together the episodes Angie… Angie and The Ozerov Inheritance (two tonally very different instalments). You didn’t even get the proper opening credits – somebody had slapped John Barry’s fantastic theme tune across a scene lifted from a third episode (To the Death, Baby) and left it at that.

And it was screamingly not a film. First Danny Wilde encounters an old childhood friend who’s up to Bad Stuff in Monte Carlo… and once that was resolved, in a totally unconnected narrative he and Brett Sinclair got caught up in an Anastasia-style plot in Switzerland.

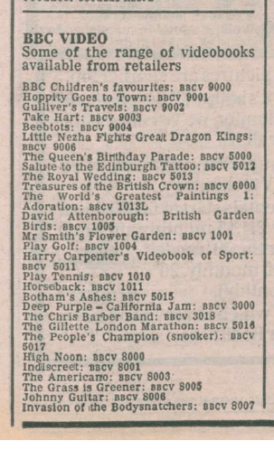

Fig 2: To quote Count Moriarty: “And there’s more where that came from…

Now, this was nothing new. Trying to foist cinematic packages on an audience which had simply been assembled from a television show was a popular industry technique in late 1940s and early 1950s. If you had plans for a new series, you shot three episodes. Then, if you sold your show, you could shoot 36 more to give you an attractive package of 39. If there were no takers, you simply stitched the footage together as a 75 minute support feature, and recouped the costs as best you could around the fleapits and drive-ins.

Take a look at Captain Scarlett (1953) next time it comes around on Talking Pictures. You won’t find any Mysterons, but you will find what is a dry-run for the very important British film series The Adventures of Robin Hood (1955-1959). Richard Greene stars as nobleman returning from war to find that he has been unjustly deprived of his estates in France following Napoleon’s fall. And it’s blatantly the opening three episodes of a series to set up the hero, his plight and his side-kicks… all of whom have the scent of Sherwood Forest about them.

Captain Scarlett was shot in Mexico – where union rates for technicians were more favourable –during December 1950. It was also rather lavishly made in colour – making it a more attractive cinema proposal. After a British cinema release in 1952, it haunted the BBC schedules for a couple of decades from 1983 before being sent to the great digital channels in the sky.

Captain Scarlett wasn’t alone. Check out Colonel March Investigates (1953) [i]. Or a variety of support films such as The Ghost of Crossbone Canyon (1952) stitched together from episodes of Wild Bill Hickok (1951-1958). Or Frontier Rangers (1958) – aka three editions of Northwest Passage (1958-1959) stuck together for British cinemagoers who would have been blissfully unaware of the TV show’s existence. All way before MGM chose to exploit The Man from UNCLE (1964-1968) in a similar manner [ii] or ITC sought to repackage the tales of Gerry and Sylvia Anderson as TV movies in a post-Star Wars (1977) world of broadcasting.

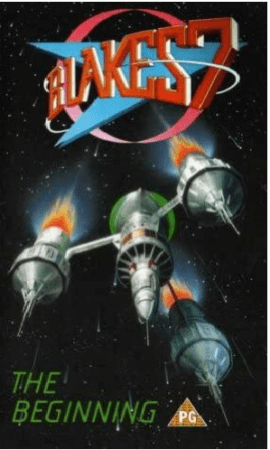

At least similar movie presentations were a little more subtle for serials or shows with ongoing narratives. An early release of the landmark children’s drama Grange Hill (1978-2008) as a BBC videobook [iii] took elements of the first series – nine 25 minute shows – and telescoped them down to 106 minutes, packaged in a box explaining that this was ‘Adapted from Series I of the award-winning children’s TV drama’. Purchasers of Blake’s 7: The Beginning would be delighted to own decent quality copies of 121 minutes of the series in 1985… even if this meant that the opening four 50 minute episodes which offered a linked ‘set up’ narrative had been compressed to little over half their length – comprising around 15 minutes of the opening instalment, a near-intact second episode, a third show which suffered various cuts, and then a conclusion pared to half its runtime.

Serials such as Doctor Who (1963-whatever) tended to fair better – a narrative comprising four 25 minute shows compressed nicely down to around 90 minutes once opening and closing credits and recaps had been trimmed… because, heaven forbid one should be subjected to regular bursts of a top quality theme tune.

But… that’s where all of a sudden it all goes wrong. And you lose the rhythm. And the fun. Cliff-hangers seem contrived or end up emasculated.

Back in 1998, the BBC Radio Collection decided to release restored versions of the captivating science fiction serial Journey into Space (1953-1958) on cassette. A good move. The bad move was when they decided to edit each narrative into a single item; as such, the epic 20 instalment The Red Planet ended up as single tale running to just under 10 hours… and was robbed of its tension in the process.

One of the finest cliff-hangers I’ve encountered comes at the end of the second episode and is pure radio – Captain Jet Morgan aboard his flagship Discovery is desperately trying to establish what has happened on Freighter No 2 via the radio link when suddenly the construction engineer Whittaker aboard the other vessel starts behaving strangely and breaks contact. Screaming for a response, Andrew Fauld’s performance as Jet climaxes perfectly as Van Phillips’ atmospheric closing theme ominously crashes in…

… except that on the 1998 version, where the muted reprise from the third episode is used. Why? Because Andrew Fauld’s electrifying delivery reaches a point at the end of the original recording where it has to stop; it is so heightened, it cannot continue. So he had to start the next recording lower. Which loses that magical edge which made it all so exciting in the first place.

And the whole point of Journey into Space at its best is the cliff-hangers. What has happened to the crew of Freighter No 2? Whose is the strange voice calling Luna on the radio? Can the land trucks make it across the Martian surface in their race against time? You had to wait a week – or at least the length of closing and opening credits – to find out.

The enforced binge-experience packaging removed so much of what the broadcast original had been all about. So, all in all, there were times when it was far better to know that you were seeing something crafted for the big screen – rather than a cunningly concealed binge watch. Suddenly, the decision by the management of Grace Brothers to send the staff of the ladies’ and gentlemen’s departments on holiday together on the Spanish Costa Plonka didn’t seem quite such a bad one after all…

Andrew Pixley is a retired data developer. For the last 30 years he’s written about almost anything to do with television if people will pay him – and occasionally when they won’t. He has no idea at all why you’re still reading these things (especially when you have proper stuff on this website that people have actually put time and thought into), and can’t work out why you don’t just wait for the movie compilation version. Or, maybe, an end-of-series compilation where he and his wife look back at all the best bits. Assuming there were any best bits in the first place.

Footnotes

[i] The three pilots were filmed in summer 1952, after which the series – Colonel March of Scotland Yard – went into production from March 1953. The film version was certified in April 1953 and in circulation by July 1953… but the TV show didn’t air in the UK until ATV screened it as part of the brand new schedule for commercial television in September 1955. So when those three episodes turned up on the box, some viewers would have already seen them at the cinema. Oh, and you can watch both the film and the series on Talking Pictures.

[ii] Actually that another one that’s fascinating – you end up with an episode made from bits of film made to turn other episodes into films. Let me explain… So, they shoot the pilot for the series – in colour – in November 1963 when it was still called Solo and – after further shooting in March/April 1964 – this airs in truncated form in black and white in September 1964 as The Vulcan Affair while the extended version becomes a cinema feature for non-US markets called To Trap a Spy (1964). By now, the series had entered production in black and white during June 1964, and in August/September 1964 they’d also shot an episode called The Double Affair in colour in the usual seven days, but then spent an extra three days shooting more footage to turn The Double Affair into a longer movie edition called The Spy With My Face (1965). Then the really clever bit is that in January 1965 they then made the episode The Four Steps Affair which basically joined together the new sequences shot to expand The Vulcan Affair into To Trap a Spy and The Double Affair into The Spy With My Face. In the UK, you could see To Trap a Spy in cinemas in May 1965, even before BBC1 started screening The Man from UNCLE at the end of the June. Naturally, the BBC didn’t air the episodes which had been reassembled for cinema audience.

[iii] Yes, that’s what they called them.