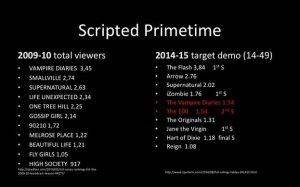

“The US network The CW celebrates its ten-year anniversary this year.” That is the opening sentence of the call for papers for an upcoming conference at the Université Bordeaux-Montaigne that makes the CW its main focus. “Network” – for the CW that has been a defining term, maybe one limiting the young station at its onset. Competing with peer networks has been one of the CW’s major hurdles to overcome, its status as network continuously forcing it into unequal comparisons, allowing critics and scholars to dismiss the CW as a failing “network” and ignore its programming. Of course the programme often regarded as teen-girl TV was considered easy to ignore by many of the more easily heard academic voices. Negative press for the CW arguably reached its low point in 2010, still and commonly contextualised by comparisons to the big four networks; the station had continuously low ratings, even when compared to cable stations, and especially when taking into consideration its most desirable 14-35 target demo.

In fact, created through the merger of UPN and the WB in Fall of 2006, many deemed the CW dead on arrival, albeit others prophesised immediate success with the new target audience, female viewers aged 18-33. Its president at the time, Dawn Ostroff, quickly reworked scheduling and shows to cater to an extreme-niche target audience, attempting to solidify a clear brand identity. It is that brand identity that has been evolving rapidly in the past four years, undergoing massive changes both in programming and industry strategies, and now has made the station “worthy” to be the focus of an academic conference.

I have argued for the CW and its shows for years, and while I’m happy to see it finally receiving attention for its innovation rather than its “shock value” (Gossip Girl, for example) I cannot ignore the gendered politics that seem to be at play in this change. That and the hierarchical obstacle of being seen as a “network” rather than a cable station (which it shares more important and defining characteristics with) need to be addressed before we can move on to appropriately frame any of the CW’s offerings, both online and on television.

2012 marks a turning point in how the CW is discussed by critics; it was the season after Dawn Ostroff’s reign had come to an end. Cory Barker stated in a side note on Ostroff and the station’s lack of success that “it’s totally her fault […]” even though he admits this would be too simplistic an analysis. He thereby echoes much of the critical response to the CW’s ongoing troubles at the time, its lack of generating an audience sizeable enough by comparison to the networks and its problem of having any defining characteristics besides offering teen-girl programming. Mark Pedowitz, taking over in mid 2011, swiftly affected changes in the station’s line up and its brand. He could have looked at early critical successes (of grandfathered-in series) and fan favorites, such as Buffy, merging girly with girl power, reviving super hero stories and encouraging programming that is experimenting with masculine and feminine narratives to increase not only viewership, but critical attention…and maybe, ‘praise’. [1]Fan audiences as well as the buzz of earlier CW shows, such as the WB carry-overs Smallville, Supernatural, and Gossip Girl, did not find critical acclaim, and as exceptions to the rule could not … Continue reading Bias within media and television studies towards specific genres, especially when gender is a specific marker for the programming, needs to be addressed to avoid a discussion that centers on canonical debates.

In the years between what Barker calls a “brand refresh”, CW’s Pedowitz’s strategies were not only debated as “last chance” options but seen as ahead of TV industry times. Lifetime, Spike, SyFy, and other cable stations all worked on adapting and shifting their brand identity, and many are reorganising their recognisable attributes again right now. For example, AMC had successfully altered its brand, receiving much critical acclaim with series such as Breaking Bad and Mad Men. Now, however, it is mostly linked to its zombie franchise, again struggling to renegotiate its audience appeal and brand identity. Ostroff had narrowed the CW’s programming’s appeal too much. While the station is indeed in operation and budgeting much more akin to a cable station than a network, it may have suffered from too extreme a niche. Pedowitz’ strategies tried to build on the existing viewership, catering to its content interests, viewing practices, and participatory cultures in order to expand the existing and attract a new viewership from there, one show at a time. The strategy, while taking years to play out, did not go unnoticed. Todd VanderWerff at a 2012 TCA tour remarked on the fact that Pedowitz’ changes were catering perfectly to the Internet driven audience. Both he and Alex Israel feared, however, that being ahead of time was risking the station’s by-a-thread survival as audiences and critics in general did not recognise the CW’s real potential that quickly.

If you were going to create a TV network that catered to the modern TV fan, it would be a network that aired lots of heavily serialized shows that were addictive and engrossing once you got into them. It would be a network that cared less about immediate Nielsen ratings and more about DVR plays and (even better) digital streaming. It would be a network that wouldn’t cancel long-running shows out of nowhere and would, instead, announce that a show was ending, but only after a shortened final season designed to wrap up its plotlines. Such a network would also feature a frequent focus on genre fare, because the modern TV fan likes that sort of thing. Maybe it would air longtime Internet favorite Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog in its television debut, coming up on October 9th. Here’s the thing: That network exists. It’s called The CW. It does all of the things above, right down to Dr. Horrible (coming on October 9th). And nobody watches it. -VanDerWerff (2012)

Four years later, the CW has a full range of series exclusively produced for its sister web-site, and has begun providing access to all of the CW shows (much to my dismay removing it from HULU, and thereby from ad-free streaming). The online site is the destination for the station’s comedies, for example, locating specific genres on specific platforms, using existing research on viewer practices. In this context, it is also necessary to mention how CW shows being picked up by Netflix seems to impact on brand perception, particularly with the market segment the station targets predominantly. In a more global context, pay TV providers such as Sky have begun to pick up CW series and air them alongside their HBO licensed content, shifting brand perception yet again. [2]Some series, such as AMC’s Breaking Bad, have been Netflix success stories. The show’s ratings went from season four’s 1.9 million finale viewers to well over ten million live-viewers at the … Continue reading As a student of mine recently wrote for a class presentation “It must have some worth and be good if they put it on Netflix” followed by extensive peer-nodding. The strategies, put in place only four years ago, have raised the average age of viewers by three years, affected, as you can see, the numbers of both male and female viewers across the board, gaining, in some demographics up to 25% of male viewers. So brand-perception, including the perceived audience of the station, content, and actual station leadership have all undergone a masculinising-facelift it appears, as we see below, and this even extends to the female characters.

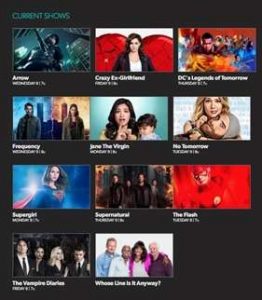

The CW’s programming now provides content clearly meant to enlarge the audience, engage not only female viewers but a male audience and go beyond the limiting age demographic. Its original series now feature female leads that break with gender norms, inviting viewers to equally break with their reading of such norms. The lead of the Vampire Diaries (SPOILER ALERT) has been buried, and it seems female characters, good girls pining for bad boys and leading ladies who are damsels in distress, have been buried right alongside her. The CW’s lineup now is filled with queens, war ladies, (crazy) women, virginal mothers, and …dead girls, … and a bunch of guys in costumes or… with bare chests (because while hero TV may cater to cis-male audiences, we don’t want to ignore all those that may enjoy the objectification of a male body). [3]Beyond the scope of this blog, I’d invite the readers to look up these series premises as they show an impressive range of programming, and the CW’s capacity for innovation.

Considering the overall breadth of content, within which we can locate a DC comics franchise, but that is nonetheless expanding its holdings outside of the same, it serves to provide some examples. The 100 and iZombie are probably the most obvious choices to discuss in relation to masculinisation. These shows have masculine traits in narrative, genre, and female lead characters. Here, women are not only in charge, but time and again table their emotions to make smart, and/or logical decisions, are leaders in their plot lines, not just leads in a cast. In these shows, men more often than not give into emotions and are both sensible and irresponsible, trades classically reserved for female characters.

The question is, are these females, their stories, and thereby the station itself now reaching new levels of legitimacy through this masculinisation of genre and narrative modes? Even the more obviously melodramatic shows, such as Jane the Virgin, add levels of complexity not innate to melodramatic storytelling. Has the station’s value increased by adding classically male coded genres to the station’s line-up, for example The Originals, a spin-off of The Vampire Diaries presenting plots reminiscent of the Godfather not a romance novel? But then we are left asking, what markers are we looking for that deem a show, a station, a narrative worthwhile our attention?

In light of this, I argue that the CW, much as other contemporary television, has begun to offer “an array of strong and independent female heroines, who seem to defy – not without conflicts and contradictions, stereotypical definitions of femininity” (Jowett 18). Some popular contemporary examples include Emily Thorne in Revenge, of course post-Angel Buffy Summers in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and certainly, to an extent, Daenerys Targaryen from Game of Thrones. Their storylines reestablish conventional femininity that is defined by its relative position to the masculine forces in play, true. But, while each of the aforementioned characters maintains feminine characteristics, much as the women of non-romantically driven series on the CW, they are not constructed around their emotional, masculine centered, hetero-normative and highly conventional romantic needs. Instead, they are either removed or distance themselves from emotional, while not physical, desire; often vocalising that such tethers can cloud logical judgement.

While many viewers see the inclusion of both masculine and feminine characteristics in contemporary television heroines, anti-heroines, and strong women-led storylines as a positive and realistic portrayal of modern women, some argue that because most heroines acknowledge and use their feminine figures and sexuality as a tool to manipulate men into getting what they want, they are in turn appropriating the male gaze and objectification of the female body. iZombie continuously bends gender identification processes, as we follow the titular zombie, Dr. Liv Moore into the morgue, her place of work, to watch her find the killers of murder victims. She does so, reminiscent of Pushing Daisies, by seeing the victim’s past. This happens – she is a zombie – by her cooking and consuming the brain of the dead. The voiceover guides viewers through each episode of the complex drama, allowing us to participate in the zombie’s character shifts. When she consumes a dead person’s brain, character traits as well as memories are temporarily transferred to Liv. It is these character traits that then become foregrounded, not the victim’s own gendered experience and existence, but the character traits channeled through Liv. The show’s layered narrative style – episodic, seasonal, and series arcs in play – its generic conventions of detective stories reminiscent of hard-boiled fiction, gender bending brain-consumption, and strong lead character cater directly to contemporary audience needs: complex, entertaining, hybrid-genre setting… but still the CW struggles for recognition on a broader spectrum and with the more established male voices in academia.

Once Israel saw the “… CW [as] the future of television,” while wondering why it was also failing in attracting viewers (Israel, 2012). It turns out that the re-branding efforts just took some time, it appears. The 2012 series receiving attention, Arrow and The 100, were making serious promises: opening the market to male viewers, and being noticed by male voices. If you hadn’t noticed, all critics were male, debating the station’s worth and place in TV industries, and television criticism itself. Legitimisation and especially legitimisation by way of masculinisation can take many forms, and recognising such changes may sometimes be a challenge. There are certainly those out there, who would argue that the CW has not changed at all.

Bärbel Göbel-Stolz is currently a guest Professor at the Department of International Media Management at Karlshochschule International University, in Karlsruhe, Germany. She teaches courses in television industries, texts, and cultures. Her current research project focuses on television trading practices both in the U.S. and abroad, investigating programming, distribution and marketing of U.S. television in relationship with foreign (non-intentional) audiences, the Foreign Programme Adopters (FPA). She recently published work on German Public Television industries, Pay Television production outputs in Germany, and the history German Crime Television, exploring changing audience tastes and trade requirements.

References

| ↑1 | Fan audiences as well as the buzz of earlier CW shows, such as the WB carry-overs Smallville, Supernatural, and Gossip Girl, did not find critical acclaim, and as exceptions to the rule could not change the general perception of the imminent CW death. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Some series, such as AMC’s Breaking Bad, have been Netflix success stories. The show’s ratings went from season four’s 1.9 million finale viewers to well over ten million live-viewers at the series final installment. The series gained traction both in the U.S. and abroad after Netflix added it to its catalogue. http://www.ew.com/article/2013/09/30/breaking-bad-series-finale-ratings |

| ↑3 | Beyond the scope of this blog, I’d invite the readers to look up these series premises as they show an impressive range of programming, and the CW’s capacity for innovation. |