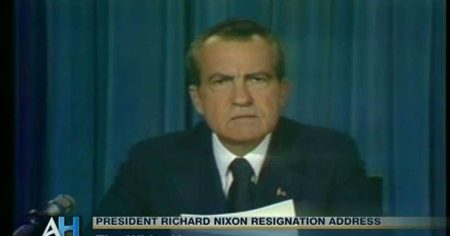

Beginning with the popularization and mass availability of television in the 1950s, the medium has since extensively been employed to transport and mediate history in manifold ways. From early newscasts of Queen Elizabeth II.’s coronation ceremony in 1952, to a collection of devastating and traumatic events such as the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, the Watergate scandal (1972), the Challenger (1986) and Columbia (2003) spacecraft disasters and the cataclysmic event of 9/11 (2001), that burned themselves into the collective subconscious through television images – all those events rapidly evolved from news broadcast to what Marita Sturken has famously labeled “instant history”[1].

Moreover, television also plays with history and provides its audience with a plethora of factual and fictional accounts of our past: myriads of biographic accounts of historic figures as well as documentaries bring history closer to millions and millions of viewers. Summarizing this impact history on television has on contemporary US culture, Gary Edgerton states: “[T]elevision is the principal means by which most people learn about history today. TV must be understood (and seldom is) as the primary way that children and adults form their understanding of the past.”[2]

Motivated by larger shifts towards the ‘cultural turn’ and later ‘pictorial’ and ‘narrative turns’, historical research has begun to approach history more as a narrative process than the traditional dualism of present vs. past. Or, according to historian Frank Ankersmit: ‘The mentality of the realistic novel and of the writing of history – as Hayden White has repeatedly pointed out – is the same’ (Ankersmit 1994, 143).

Also adding to the interdisciplinary exchange of history and media was the major shift in the understanding of history’s relation to memory that correspondingly took place during the end of the 20th century. Research in the field of cultural memory studies rooted in the works of Maurice Halbwachs, Aby Warburg, Juri Lotman, Pierre Nora and Jan and Aleida Assmann tend to conceive of both concepts not as conflicting binaries, but rather as mutually interwoven entities.[3] In the tradition of the late historian Hayden White, Marek Tamm fittingly sums this up: “In terms of cultural memory, history is a cultural form exactly like, for instance, religion, literature, art or myth, all of which contribute to the production of cultural memory. And the writing of history should be treated as one of the many media of cultural memory, such as novels, films, rituals or architecture.”[4]

Consequently, at the nexus of Cultural Memory Studies, History, and Media Studies, an interdisciplinary common ground can be found in the assumption that history and memory are both mediated and mutually interact with media. This understanding is crucial to the poststructuralist ways in which history as narrative nowadays becomes repurposed in a multitude of different ways.

In the following, I will take a closer look at a particular way of repurposing history in television via the genre of Alternate History. Evolving towards a mainstream genre during the early 1960s, many science-fiction series mused about the possibilities of time travel and alternate histories: how history could, from a more enlightened contemporary viewpoint, be revisited and altered to make past mistakes forgotten, or else how our history would turn out, would other beings have tampered with history as we know it.

Prominent examples from more than six decades of television history mark that trend in science fiction. Shows such as Flash Gordon (DuMont, 1954-55), The Outer Limits (ABC, 1963-65), The Twilight Zone (CBS, 1959-64), Doctor Who (BBC 1963-89; 1996; 2005-), Star Trek (NBC & other networks, 1968-2005)[5], Quantum Leap (NBC, 1989-93), The X-Files (FOX, 1993-2002), Forever Knight (CBS, 1992-6), Dark Skies (NBC, 1996-97), and Timecop (ABC, 1997) developed two distinct scenarios that could be labelled ‘revisionist’ history on the one hand, and ‘alternate’ history on the other. Throughout the decades, revisionist history series usually displayed white male protagonists moving back in time so as to eliminate notorious historical personae (among them Hitler and Stalin), prevent slavery and the Holocaust from happening, or to alter historical timelines in other ways for what, from a contemporary perspective, was deemed the better alternative. On the other hand, shows such as Star Trek, Doctor Who, The X-Files or Dark Skies introduced alternate histories that added a twist to culturally-traumatic experiences from the past by adding supernatural elements to a historically-motivated narrative: Dark Skies, for example, puts space aliens behind the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and in Doctor Who and The X-Files, Mussolini and Nixon are aided by mean spirits on their respective ways to power.[6]

For Steve Anderson, all these science-fiction narratives share an expression of contemporary neuroses, collective fears and cultural ambitions that vibrate with the early-postmodern fear of the loss or collapse of history itself. This existential fear still forms a key element in modern complex SciFi and time travel series such as Fringe (Fox 2008-13), Life on Mars (BBC, 2006-7) and Continuum (Showcase/SyFy, 2012-).

In the here and now of 2018, Alternate History TV has gained even more momentum. A new wave of shows including Timeless (NBC, 2016-), SS-GB (BBC, 2017), Making History (FOX, 2017– ), Frequency (The CW, 2016– ) and, as might be argued, large parts of the Marvel Universe that has quite recently also captured our television screens – see William Proctor’s take on Netflix and the MCU, or my own two penny on Legion – continue in the tradition of the big “What if?”.

Alison Landsberg has recently scrutinized how a production of knowledge about history and the past can be facilitated through a variety of visual media including television. Dissecting theories of identification with on-screen characters and a corresponding mobilization of affect, Landsberg develops a particular mode of engagement that she sees to be at work in such period dramas: these ‘historically-motivated’ shows, she argues, employ strategies of affective engagement that draw on both empathy and alienation by “fostering moments of critical encounter, the texts […] highlight the relays between affect and meaning-making, processing and analysis” (Engaging the Past, 178). Doing so, they activate the audience into reflecting about what they are encountering on-screen. Building on Landsberg’s approach, I argue that the workings behind alternate history TV drama are quite similar, but I also want to add another layer: alternate history does not only draw on affect and empathy, but also on nostalgic memories.

Stephen King’s 11.22.63, which was produced by J. J. Abrams as a finite miniseries for the US streaming giant Hulu, might be classified as a classic tale of time travel. At its starting point, a high school teacher finds out that a friend possesses a portal that allows one to travel to the year 1960. But, obviously, certain rules apply. Let me just exemplify this via the show’s trailer, which sums up the narrative setup quite nicely.

cstonline.netvimeo.com/262766771

In 11.22.63 we follow protagonist Jake Epping on his quest to find and stop the assassin who killed JFK. During his first attempts to settle into the world of 1960, we re-encounter this era through his nostalgic gaze and marvel both at the level of detail and verisimilitude that the narrative world boasts, and the seemingly simple and good life that the inhabitants of that world are living. But soon, Jake – and we as viewers – learn that not all has been jolly and well over in this increasingly foreign country – to borrow historian David Lowenthal’s words –that is our past.

Watching 11.22.63, we find ourselves in constant flux between a state of nostalgic longing of the oh-so-sweet-and-polished imagery of the early-60s’ United States, and the repeated shocks and disruptions such as the attack on Jake when he uses the phone booth – when the past fights back in the narrative of 11.22.63. Here, I see a similar mode of affective engagement at work as the one put forward by Landsberg, which not only draws on empathy and alienation, but is extended by actively manipulating our nostalgic memory of the 1960s. And a similar strategy can also be identified in the second example that I wanted to discuss here.

The story behind The Man in the High Castle, which has been produced by Frank Spotnitz and Ridley Scott for Amazon[7], has by now itself become an important staple of popular culture[8]. At its core, it asks how life in the United States would look like if WWII had been won by the Nazis and their allies. In this alternate universe, the US as we know it has become a Divided States of America: separated by a central neutral zone, the Eastern part is ruled by the “Greater Nazi Reich” while the West is occupied by Japan. Fifteen years after the Allies lost World War II in this alternate universe, we are introduced to the lives of two young Americans who stumble across a mysterious piece of film that offers glimpses of an alternate, alternate reality: the actual defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945. Trying to trace the origins of this film, these two begin a cross-country odyssey in order to connect with an underground resistance group.

Around this main plot, the show spins a thrilling investigation into the possibilities of how life as we know it could have turned out, would a key moment in history have been different. And while many aspects of the show are worth debating (from the choice of actors to the producers’ questionable choice of marketing strategy, what I want to particularly highlight here is the efficiency of how this show draws on now-common staples of retro and nostalgia. In this context, I consider The Man in the High Castle an intriguing example because it transplants our assumed knowledge of 1960s America into the setting of an alternate timeline and actively puts nostalgia on its head by subverting our expectations. This is quite fittingly illustrated during the first minutes of the show’s pilot.

cstonline.netvimeo.com/262766464

Here, we find ourselves thrown into a meticulously-crafted facsimile of the 60s’ New York, in which much of the visual iconicity is referenced, but also altered – right up to the moment when we find the iconic shot of 1960s Times Square mutilated by the presence of a disturbing amount of Nazi insignia. We are both drawn to an imagery that seems oh so very familiar – but we’re also pushed away by a feeling of absurdity that is triggered by the Nazi symbols hanging in one of New York’s most famous locations.

Further playing into this larger strategy is the show’s title sequence, which has its own way of introducing us to the alternate world of The Man in the High Castle. The producers chose a song from the iconic 1965 musical/movie The Sound of Music and came up with a haunting remake that I think perfectly fits the overall theme of the show. Let me just show you a back-to-back comparison of the two …

cstonline.netplayer.vimeo.com/video/262764924

In my opinion, the twist here is particularly haunting both because of, and despite its familiarity. Here we have an iconic tune from The Sound of Music, which is transformed from a love song into an anthem of dystopia. Doing so, this show takes common feats of nostalgia and subverts them. All in all, and throughout the first season, the most disturbing parts of the show are the ones when we encounter normal All-American day-to-day life, but are also forcefully reminded by little, somewhat-offish details that this life has completely adapted to the appalling politics and rule of the Greater Nazi Reich. We are constantly lured in to succumb to nostalgic feelings, but on many occasions, this longing is forcefully disrupted via a narrative about an alternate universe that has at its core the tyrannies of fascism. The same goes for the show’s second season; here’s a sneak peek into the first minutes of S02E01:

cstonline.netvimeo.com/262765390

So, drawing from Alison Landsberg’s notion of ‘historically-conscious drama’, it can be argued that a recent wave of alternate history drama employs similar, but extended strategies that lead to an extended mode of engagement. What I hope to have been able to show is that this extended mode of engagement is able to create affective proximity as well as detachment through an evocation of nostalgic feelings and empathy, but also of distancing effects via creative remediation and modulation of our cultural memory. Therefore, I see these recent cases of alternate history TV as persuading us into re-considering our received conception of U.S. popular history.

Tobias Steiner has studied in Hamburg and London and holds an MA in Television Studies from Birkbeck, University of London. He has taught U.S.-American Television history at Universität Hamburg, Germany, and currently works as a research fellow in open education and open science at the university’s Universitätskolleg.Digital. He is currently the YECREA representative of ECREA’s Television Studies section and has published on a variety of topics both here on CSTonline and elsewhere, ranging from questions of authorship in Game of Thrones to the transnational renegotiations of Nordic Noir (in print, 2018). See his ORCID profile for further information and list of publications.

Footnotes

[1] See Sturken, Marita. 1997. Tangled memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS epidemic, and the politics of remembering. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 6.

[2] Edgerton, Gary R. 2000. “Television as Historian: An introduction.” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies 30.1. p. 7. Online at: muse.jhu.edu/article/400195.

[3] See e.g. Berliner, David C. 2005. “The Abuses of Memory: Reflections on the Memory Boom in Anthropology.” Anthropological Quarterly 78.1: p. 199. DOI: 10.1353/anq.2005.0001.

[4] Tamm, Marek. 2013. “Beyond History and Memory: New Perspectives in Memory Studies.” History Compass 11.6: p. 463. DOI: 10.1111/hic3.12050.

[5] Star Trek: Original Series (NBC, 1966–69), The Animated Series (NBC, 1973–74), The Next Generation (independent stations and ABC, NBC and CBS affiliates, 1987–1994), Deep Space Nine (Paramount pictures syndication, 1993–99), Voyager (UPN, 1995–2001), Enterprise (UPN, 2001–05).

For more extensive accounts of how Star Trek remediated historical events, see e.g. Bernardi, Daniel. 1998. Star Trek and History: Race-ing toward a White Future. New Brunswick, N.J. Rutgers University Press. Or: Reagin, Nancy R. 2013. Star Trek and History. Hoboken, N.J. Wiley.

[6] Cf. Dark Skies S01E01 “The Awakening” NBC: 09/21/1996; and Breaking Bad showrunner Vince Gilligan’s directorial debut on The X-Files ‘s 21st episode of season 07, titled: “Je souhaite” FOX: 05/14/2000; Forever Knight S03E19 “Jane Doe” CBS: 04/27/1996.

See Anderson, Steve F. 2011. Technologies of history: Visual media and the eccentricity of the past. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press. p. 19.

[7] Spotnitz left the series after Season 2, see e.g. http://variety.com/2016/tv/news/man-in-the-high-castle-frank-spotnitz-exit-showrunner-amazon-1201779301/.

[8] The “What if Nazi Germany won WWII” trope still proves an important cornerstone of alt-history television, see e.g. The Guardian’s early appraisal of, and later disappointment about the BBC’s recent SS-GB (2017).