This is a taster of a chapter I have just published about unusual and expressive uses of sound in TV.[1] The chapter is in one of the Moments in Television series books that I blogged about recently, and focuses on an episode of the science fiction series The Twilight Zone: ‘The Invaders’ (1961). The episode has no dialogue, though it has some narration spoken to camera and some music, and the absence of speech made me think about what sound in TV drama does. The central character in ‘The Invaders’ is played by Agnes Moorehead, and sounds produced by her mouth, her body and as a result of her actions, as well as sounds coming from alien invaders, carry an extraordinary weight because of the lack of audio information in speech. Framing narration at the start and end of the episode gains great significance because these are almost the only words on the soundtrack, identifying – and misidentifying – the nature of the fictional world.

A middle-aged woman, living alone in a wooden cabin, is disturbed by strange sounds coming from her roof. Upon investigation, she finds a miniature flying saucer there, and two six-inch high astronauts emerge from it and explore her house. She fights them off, and they defend themselves with miniature ray-guns and the woman’s household objects, until she kills one of them. She attacks their flying saucer with an axe, and inside it she hears the voice of the second astronaut warning other travellers about the dangerous giants on this planet. She destroys the spacecraft, which turns out to be an exploration ship from Earth.

Rod Serling’s narration, which introduces the episode, is a key sonic anchor. The Twilight Zone’s half-hour science fiction and fantasy dramas were created and produced by Serling’s production company for the CBS network, and his voice and visual appearance are key to the series’ identity.[2] ‘The Invaders’ begins with a title sequence that shows wreaths of mist dissolving to reveal a graphic of a bright orb. A repeated, spiky musical motif by the French avant-garde composer Marius Constant gives way to a more fully orchestrated but dissonant tune. Conventional orchestration is melded with avant-garde and Modernist forms. Serling’s voice-over announces: ‘You’re travelling through another dimension. A dimension not only of sight and sound, but of mind.’ Sound and music support the images here, establishing a space between classical and contemporary musical styles, between pictorial and graphical representation, and between the viewer’s sense of normality and an Other reality which is psychological rather than physical. Serling’s voice continues: ‘A journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination. That’s the signpost up ahead, your next stop: the Twilight Zone.’ Sound and vision orient the viewer for what is to come; an aesthetic experience that promises to be thrilling and otherworldly.

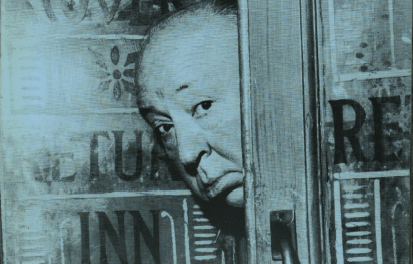

The camera arrives in a night-time landscape, a rural place with scrubby bushes in the foreground and the dark silhouette of a small house behind them. A single lighted window can be seen in the house, and wisps of smoke come from the chimney. The setting might suggest a Western, or an agrarian melodrama in the Depression era. This episode seems rooted in American mythologies about pioneer homesteading and self-reliance. The camera moves towards the farmhouse’s window, through which a middle-aged woman can be seen. She is cooking, adding ingredients to a large pot. Serling walks into shot, dressed in a business suit (Fig. 1). He is out of place, and his visual appearance and vocal tone are disconcerting as well as helping to orient the viewer. Serling’s words hint at these genres: ‘This is one of the out-of-the way places, the unvisited places, bleak, wasted, dying.’ The story is about home invasion, but the surprising twist will be that it is the woman who is a violent, alien Other, rather than the outsiders who try to enter. As in Freud’s work on the uncanny (unheimlich), the homely becomes frightening and estranged.[3] The sounds and images that we see at first are in fact working to mislead us.

Previous writers (like M. Keith Booker (2002) and J. P. Telotte (2010)), have placed The Twilight Zone in a transitional moment between the ‘theatrical’ live studio-shot single TV play and the filmed drama that succeeded it.[4] Their arguments are largely about the relationship between dialogue (‘theatrical’) and visual aspects (‘filmic’). Conversely, in ‘The Invaders’, theatricality in the form of bodily, expressive performance is integrated into the emergent filmed TV drama form without any spoken conversations at all. The episode seems like a commentary on this historical turning-point in TV history.

The woman slices vegetables, absentmindedly putting a piece in her mouth and chewing it. The chewing sound heralds a shift in tone: the music stops and is replaced by mechanical humming, then the woman covers her ears with her hands as an electronic shrieking noise becomes very loud. She seizes a lamp and climbs a ladder up to the kitchen roof. The music disappears, leaving a silence in which we hear another piercing electronic sound. She sees a metal disc-shaped object on the roof.

The spacecraft looks like many flying saucers from 1950s and 1960s cinema and television; indeed, this prop was originally built for the film Forbidden Planet (1956).[5] Sound effects very like the electronic sounds of Forbidden Planet strongly contrast with the grunts, gasps and scraping noises made by Moorehead’s mouth and body. Around the roof hatch, a six-inch high figure, its arms outstretched, lumbers slowly forwards. In a sudden movement the woman’s foot knocks it down the hatch, she slams it shut. A close-up shows her sweating face and dishevelled hair, and we hear her panting in terror. We have moved from a Western setting to science fiction, and towards the horror genre.

Moorehead’s performance now emphasises her vulnerability to attack from the tiny astronauts, and her increasingly violent defence against them. Bursts of music accompany the sequence, and flashing lights and buzzing sounds from the creature indicate a ray-gun attack on the woman’s body. The camera shows the blistered skin of her hand, forearm and chest, and louder, stabbing musical motifs on the soundtrack follow her hesitant, then sudden movements. Moorehead’s facial expressions are carved out by intense lighting, as are the wild movements of her body as she fights the intruders. The lack of speech and sparse music might remind us of Bernard Herrmann’s score for Psycho, released the previous year, and its violent shower scene.

Lighting contrasts develop further, as strong light and shadow emphasise the blade of a small axe that the woman carries, and the flash of sparks as the woman throws a wooden box onto the fire with one of the intruders trapped inside. By now, the viewer is invited both to sympathise with her plight but also to see her as animalistic and savage, a reading reinforced by the panting, gasping and cries of surprise or pain that dominate the soundtrack. (Fig. 2)

The music stops when the woman climbs the ladder to the roof again. She rains repeated axe blows onto the saucer, but she pauses when she hears a human voice inside: ‘Central Control … Do you read me? Gresham is dead! Repeat, Gresham is dead! The ship’s destroyed.’ This man’s voice identifies the woman as one of an ‘Incredible race of giants here.’ The astronaut says ‘No, Central Control. No counterattack. …. Too powerful. Stay away.’ The woman collapses, exhausted (Fig. 3). Music builds to a climax when the camera stops on the words ‘U.S. Air Force Space Probe No.1’ written on the saucer. The twist at the end of the story is communicated through spoken and written language, while mood is conveyed by music and wordless physical performance.

The tight camera focus on Moorehead, and the close-miked sounds of her body, give a sense of aliveness and presence to the visual and aural components of the programme. By minimising music, and by recording sound with multiple microphones oriented towards Moorehead’s and the astronauts’ performances, diegetic sound gives a feeling of proximity to the action throughout.

The Twilight Zone’s episodes followed the convention in 1950s science fiction of dwelling on the build-up towards a resolution, then undercutting the resolution with a twist.[6] But in ‘The Invaders’, voice and silence, familiar and unfamiliar settings, and play with science fiction’s visual and narrative conventions are used in more creative ways. The focus on sound, and on one performer in a restricted space, exploit the production and scripting possibilities available in this moment of transition as US television drama moved from ‘theatrical’ interior performances to filmed series using exterior locations. ‘The Invaders’ was exceptional and innovative in its uses of image and sound, at the very moment when the format that made it possible became increasingly alien to American television.

Jonathan Bignell is Professor of Television and Film at the University of Reading. He is a General Editor, with Sarah Cardwell and Lucy Fife Donaldson, of MUP’s ‘Television Series’. Jonathan works on histories of television drama, cinema and children’s media. Some of his work is available free online from his university web page or from his academia.edu page.

References

[1] The chapter is a much more detailed analysis, including work on historical and production contexts that is not included in this short blog version. Jonathan Bignell, ‘Alien and familiar: sounds and images in The Twilight Zone: “The Invaders” (1961)’, in Sarah Cardwell, Jonathan Bignell and Lucy Fife Donaldson (eds), Sound/Image: Moments in Television. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022, pp. 15-37.

[2] Jon Abbott (2006), Irwin Allen Television Productions, 1964-1970: A Critical History of Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Lost in Space, The Time Tunnel, and Land of the Giants. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

[3] Sigmund Freud (1953) ‘The Uncanny’, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works, trans. and ed. James Strachey, vol. 17, pp. 217-52.

[4] See Keith M. Booker (2002) Strange TV: Innovative Television Series from The Twilight Zone to The X Files. Westport, CT: Greenwood; Jay P. Telotte (2010) ‘In the cinematic zone of The Twilight Zone’, Journal of Science Fiction Film and Television, 3:1, pp. 1-18.

[5] Jean-Marc Lofficier and Randy Lofficier (2003) Into the Twilight Zone: The Rod Serling Programme Guide. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, p. 28.

[6] Stan Beeler (2010) ‘The Twilight Zone’, in Stacey Abbott (ed.) The Cult TV Book. London: I. B. Tauris, pp. 55-8.