I was initially thinking of calling this post “Is the Age of Quality Television Over?” or even something more ominous like “Is This The End?” but I don’t think that it is, and I’m not ready to play TV-Nostradamus just yet, in spite of whatever signs I might be seeing from the comfort of my living room. There’s still plenty of quality programming to be had, from Sherlock to Justified to Homeland, and, in many ways, the production values, the scripts, and the acting have never been stronger. And, if a show like Hannibal says anything about broadcast, then the networks have learned the lessons of cable, and what started with Tony Soprano’s first visit to Dr. Melfi has become therapeutic for the medium as a whole, from the police procedural to the network sitcom.

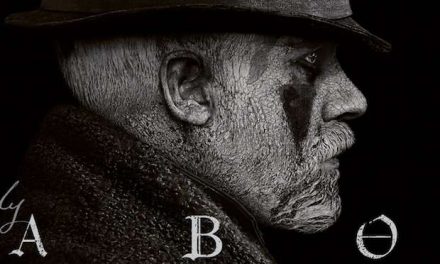

We have, though, come to a crossroads of sorts, a crossroads that was, perhaps, crystallized by the death of James Gandolfini this past summer and that is being reaffirmed by the end of so many important and influential television shows within the next year or so. While The Sopranos cut to black over six years ago, the loss of Gandolfini was more than just a celebrity tragedy. It felt and continues to feel like the end of an era of sorts. According to critic Ellen Killoran, this may be because it serves as a psychological reminder that the show and all that came with it is finally gone: “That we can sometimes so easily confuse [an actor with a character] is a testament to the way great characters and stories like those we found in The Sopranos can permeate our consciousness, twisting our imaginations into what feels like a kind of reality. In Gandolfini’s case, almost certainly, we are mourning the loss of Tony Soprano as much as we are the man who brought him to life.” If there was any element of romantic fragment to the ending of the series, any sense of possibility in that cut to black that it all still could go “on and on and on,” then Gandolfini’s death seemed to break that illusion, that Tony was still in that restaurant eating dinner or agonizing somewhere else over some new crisis to one of his various families. Whatever David Chase does from here, we will never see Tony drive through New Jersey again on his way back home, at least aside from a rerun or a binge-watching DVD marathon. Moreover, we mourn Gandolfini and Tony just as much as we mourn that time and what it meant to us, because these losses remind us that those things and that time are no more.

And most of those shows, those great television experiments, that first generation of programming that started because of The Sopranos and followed its example, are pretty much done now or will be soon. The Shield is over. Lost is over. 24 is over. Deadwood is over. Six Feet Under is over. The Wire is over. Rescue Me is over. House is over. In the next month, both Dexter and Breaking Bad will be done. And, if the reports are accurate and the showrunners can be believed, then both Mad Men and Sons of Anarchy will finish up their runs in the next year or so. What happens and where do things go after that? How will the networks fill in the void left by the loss of these shows? Do these endings mean that we are on the verge of something else, some turn, some cultural response, some backlash to all that came before, or should we prepare ourselves for the second or third generation of The Sopranos, Tony’s sons and daughters finally ready to come into their own? Or, will we really be looking at watered-down versions of what was once great, a mob boss here and a corrupt cop there, in an attempt to cash in on our affinity for those other shows and our nostalgia for the recent past?

Some signs suggest that these last two questions, in particular, are the ones that should concern us and that we are looking to find the next big thing in the ashes of the previous one, a frequent pattern of behavior when it comes to television. It could also mean that the individual narratives of those shows, as well as the larger cultural/historical narratives/circumstances that they referred to, are over and done, and we need to move on. As a number of newspapers and websites have reported – here’s one – Fox is planning on bringing Jack Bauer and 24 back for one more “day” next summer. And though Dexter and Breaking Bad are on their way out, rumors continue to circulate that both shows may be spun off in some way, to somehow keep viewers in those unique worlds. Over the summer, Showtime announced that Dexter showrunner Scott Buck had been signed to a two-year contract, adding fuel to the possibility of a Deb spin-off after Dexter is done. From creator Vince Gilligan’s interest in the project, AMC just approved a deal for a Breaking Bad prequel, tentatively titled Better Call Saul. Where Jack Bauer’s “real-time” extreme heroics may have seemed like a necessary evil after 9/11, would they seem as necessary now? Would a series about Dexter’s foul-mouthed sister or Walter White’s morally bankrupt lawyer hold our attention in the same way or seem as cutting edge as the originals did? And, in the end, would any of these shows offer us anything new?

I was watching the pilot for AMC’s new series Low Winter Sun a few weeks back and was struck by this speech from Lennie James’s calculating police detective Joe Geddes: “Folks talk about morality like it’s black and white. Or maybe they think they’re smarter or they’re at a cocktail party acting all pretentious, and then they say it’s gray. But you know what it really is? It’s a damn strobe, flashing back and forth and back and forth all the time. So all we can do, all we can do is try to figure out how to see straight enough to keep from getting our heads bashed in.” Although the show just started, this speech could easily have been delivered by the protagonists from any one of the shows that ended in the last ten years and could, perhaps, serve as a theme or mantra for the quality television movement, in general. In some way, just about all of these shows have explored the moral complexity of the world and forced us to come to grips with it by getting us to like characters who are inherently reprehensible or asking us to sympathize with good people doing bad things. The message has given us some of television’s finest hours, but, with this speech, here and now, after those ten years, it is the same message. Is there more great television to be had by plumbing that message even further through other examples of human hypocrisy—a politician who is a pathological liar, a banker who moonlights as a counterfeiter, a marriage counselor who cheats on his wife, etc., etc.? If so, how does it add to and enlarge the conversation that has come before?

From the beginning, when these kinds of shows started to air, I wondered how television eventually would respond to it, since the medium also thrives on reinventing itself, paradoxically, just as much as it does on replication. Once we were ready to move on from these morally problematic figures, where would we go? Unlike that season of Dallas, we would never be able to write it off or explain away what we had seen. So, how could we ever go back to watching and believing in “the good guys and the bad guys,” to easily identifiable heroes and villains, when quality television had offered us this highly cinematic, extremely tempting forbidden fruit, with dense storylines and fully developed characters, in high definition no less?

I won’t be trading my flat screen in any time soon for a sandwich board saying that “The End is Near,” but I do think that the answer to that question—where would we go?—could be upon us shortly, perhaps even as early as this fall, when so many of the networks roll out their line-up of new shows. After all, you can only stare at a strobe for so long, regardless of how fascinating it is. The time may be coming when we will have to close our eyes tightly, allow them to readjust, and get ready to look at something new.

Whenever it does come, whenever the screen goes dark and the last of the credits roll, my fervent hope is that what comes next in that light beyond the darkness, that next generation of quality programming, will hold us, provoke us, and speak to us as successfully as the previous one did.

Douglas L. Howard is Chair of the English Department on the Ammerman Campus at Suffolk County Community College, editor of Dexter: Investigating Cutting Edge Television (2010), and co-editor of The Essential Sopranos Reader (2011) and The Gothic Other (2004).