About two years ago, at a dinner party, with my husband to my left, I was surprised when I turned to my right to find Nancy Ford, the woman responsible for getting me my first job on a major network television soap opera. I hadn’t seen Nancy in more than 25 years. I first encountered her after she had read a sample script, based on the plots and characters of Ryan’s Hope, that I wrote for a Writer’s Guild workshop intended to introduce new writers to the genre. She was a staff writer for the show, and graciously called me to say that if I hurried and revised it I might be able to get her job. She was about to be fired. (Well, that’s a lot more than gracious, isn’t it?) She then gave me editorial advice and I sent the rewritten script to Joe Hardy, the then new Executive Producer. Within four days Joe summoned me to his office and gave me two jobs, one as a script writer and one as a consultant to the then new Head Writer of Ryan’s Hope, Pat Falken Smith. Pat had been the head Writer of General Hospital when Laura famously ditched bourgeois respectability and materialism to run away with Luke, thereby catapulting American soap opera to new fame, fortune, and, as I contended in my book No End to Her: Soap Opera and the Female Subject (1992-3), a new and exciting feminist narrative identity. As we reminisced, Nancy said, “There are no soap operas anymore.” True, that. What passes for soap opera today is only worth talking about in appreciation of “the way we were.” Soap opera has yet another new identity, probably its last, as one of the walking dead.

Nowadays, no soap producer would read an unsolicited sample script, let alone hire as a consultant a woman who had never before written for television because she had a tantalizing Ph. D. It’s a very closed, indeed airless, shop these days, mostly because there are only four American soaps left, out of a field of a dozen and more, so jobs are few and far between. But much more important, what jobs there are, though they pull down handsome Writer’s Guild salaries, are otherwise thankless and dreary. The reckless exhilaration of soap opera in its heyday, roughly between 1978 and 1994, when the networks were still ignoring it as a contemptible women’s medium, nothing more than a “cash cow,” was filled with a feminism introduced to the genre on General Hospital full throttle, albeit inadvertently, under Pat’s bizarre, but serendipitous stewardship. The fate of General Hospital is exemplary of what has happened to the genre.

Pat Smith had been a casualty of the sexism that tyrannized Hollywood in the 1940’s. Working with her on Ryan’s Hope, as her “consultant,” I could see that she was a truly talented, ambitious woman, embittered by being forced to know her place, two steps behind the male writers. She was a churning vat of unacknowledged anger which led her to be exploitative and paranoid about other women in the business. (She was sure that Joe Hardy has planted me to assist her so that I could take over her job in due course. ) I hated working with her. But she knew how to write for the soaps, and earlier, in the case of General Hospital, she had blindly channeled her rage into the story she had inherited from her predecessor as Head Writer, Doug Marland, about Laura Vining (Genie Francis), a 14 year old girl who was sexually abused by David Hamilton (Jerry Ayres). Hamilton, having pursued Laura’s mother in vain, thought he could have his way with a defenseless girl. Instead of collapsing into a heap to make herself ready to be rescued, Laura defended herself with a fireplace poker and killed her attacker. Marland’s story initiated a three decade narrative about Laura; Pat contributed the part of Laura’s arc about the collapse of Laura’s first marriage at the age of 16 or 17. Having suffered at Hamilton’s hands, Laura thought Scotty Baldwin (Kin Shriner), a handsome, aspiring lawyer from one of the town’s leading families—the focus of her puppy love–would make her dreams come true, and against her mother’s advice, refused to wait until she was a little older to exchange vows with him.

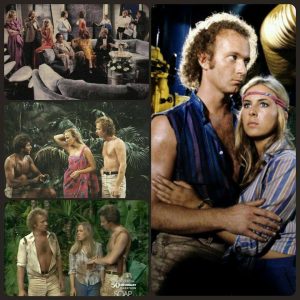

Under Pat’s fine hand, Laura’s happy ending became a disastrously wrong turn, when her ideal, chivalrous lover became her nightmarish domineering husband, who wanted to lock adventurous Laura in a doll’s house. As events transpired, Laura ran away with town bad boy, Luke Spencer (Tony Geary), a low level gangster, when he begged her to save his life from his vengeful mob boss. The story was Laura’s, as unexpected rescuer and seeker. She was trying to find her own life, as much as she was trying to shield Luke’s.

Pat’s confused anger was manifest in Laura’s rejection of convention, but there was another twist to this precedent setting story; it was connected with a rape that made Laura’s pivot toward Luke and away from Scotty both ambiguous and ambivalent as far as my claims about the structural tendency in soap opera toward feminism. Before the great escape, Laura’s relationship with Luke had grown as a result of her decision, against Scotty’s wishes, to take a job in Luke’s night club. Scotty didn’t see why a married woman should work. Laura’s rebellion led directly to her freedom from Scotty, but this arc walked her through the minefields of long established conventions that where female freedom went, sexual depravity followed. Laura’s proximity to Luke fanned his lust for her and when there came a night that he learned he was being set up by his mob boss to be killed, he decided that he would not die without consummating his passion for Laura and took her by force.

At this point, Pat cemented General Hospital’s place as a venue for dealing with sexual violence against women. The show resisted the long tradition that women like Laura get what they are asking for. It depicted the rape in brutal terms. Luke was clearly forcing himself on a terrified, unwilling young girl, suddenly the victim of a man she thought was her friend. Because eventually Luke and Laura became a couple, many feminists were enraged about what they decried as a “love your rapist” story. And from an abstract position, it is possible to see their point. He did rape her; she did come to love him. But such a reading completely ignores the way the story was played out over many months as a tale of profound atonement and earned redemption. Only after Luke understood what he had done and begged for her forgiveness did they become consentual lovers.

It seemed to me then—and does now–that the problem of misguided male entitlement was confronted very well, well enough to make General Hospital the forerunner of a trend in soap opera toward the most forthright presentation of sexual violence against women in the pop culture of the time. There was never a question of “boys will be boys.” And unlike in the widely touted feminist film Thelma and Louise (1991), in which after a rape Thelma (Geena Davis) was almost immediately able to bounce into J. D’s (Brad Pitt) bed, Laura was traumatized about sexuality for a long time after the incident. The narration of female PTSD and male shame in the aftermath of rape strikes me as feminist in many important ways. But no matter how one construes the rape and subsequent romance, the crucial point here is that story was always Laura’s, a story of a girl’s encounter with oppression; a girl’s battle for freedom and the right to her own desires. Maybe it was the first such story on television. Certainly, this did not come about because Pat was a feminist—she was openly derisive of feminism—but for a better reason. The endless structure of soap opera was made for feminist narrative, and tended in those days, to inspire the writers toward stories that were feminist in character even if that was not necessarily an intended theme.

As many feminists have noted, closure has traditionally been the moment in popular culture when the most high flying of women have their wings clipped, but soaps don’t have closure. In fact, closure is the enemy of the soaps which, in order to survive, require situations that flow—and flow. The bringers of solutions and control, that is to say the heroes in popular culture and certainly on night time TV, are the villains on the soaps. Control, valorized in most mainstream entertainment, is transformed into domination and threat on soap opera. They are the main threats to an endless story. For the purposes of soap opera, the ideal characters have always implicitly been rebellious girls/women and bad boys/men, or at least men who have been hurt by society, in many cases quite literally by fathers and patriarchy. The Luke and Laura story made this narrative tendency explicit. Many stories of exploited girls and men who learned from (or were saved by) them followed. Documenting this narrative tendency in daytime drama when I wrote No End to Her, I naively concluded that soap opera would always, by its structural nature, be feminist, because I couldn’t conceive of the perversity of going against the form in a way that would destroy it. It was a money maker, and wildly popular. Who would want to kill THAT? I underestimated the perversity of sexism in America.

Around the mid-90’s, as soap opera gained a kind of legitimacy, fostered in great part by the work of academics like me, the network officials, who had showered the genre with contempt, began to take an interest. While they were simply raking in the cash, and mocking their little gold mines, the structure-driven feminism of the soaps proceeded unimpeded. As soon as the networks gained a modicum of respect for the genre, they began to actively oversee plot development and forced sexist values onto daytime, bloating the significance of the “bad boy” until he began to eclipse the importance of the rebellious girl. This trend had catastrophic effect on both General Hospital and the genre. When Laura chose Luke and freedom over Scotty and stifling middle class security—apologies to all who still retain anger about the rape story– the soaps were born again. However, when Luke became more important than Laura on General Hospital, as he did, soap opera began to die.

Luke’s ascendance introduced an endless story that had ceased to depend on the ongoing struggles of women and girls within the clutches of patriarchy, and began to foreground the bad boy’s unending cycle of crime and regret. Laura was dispensed with, driven to madness by guilt about—well, it was never clear exactly what she was guilty about–and the soap opera that had turned the genre toward support of female autonomy sounded a sinister note by espousing the old cliché of administering punishment to the too headstrong girl. Laura was packed off to a sanitarium, while Luke increasingly became the General Hospital strong man, moving fitfully into and out of collusion with the gangster characters who had gained traction on the show. Yes, gangsters. At the same time that Laura’s story became Luke’s—Pat was now long gone from the show–in a turn of events that was equally predictive of the future of the genre, Sonny Corinthos (Maurice Bernard), who had been the show’s main villain—we had seen him hustle young girls into the sex trade, and use murder and extortion to promote his businesses—began a process of morphing into a bad boy hero.

The pattern began to take hold. On another soap opera, One Life to Live, previously focused on the ramifications of the sexual abuse by her father of the main character, Viki Lord (Erika Slezak), Todd Manning, a rapist, liar, and petty crook, usurped the stories of the women he was paired with. Luke, Todd, and Sonny were the first in a tidal wave on soap opera of what I like to call the reign of “The Contrite Thug,” constructed very much in the mold of the classical abuser. They went through cycles of abusive/criminal behavior followed by periods of self-disgust, high octane pleas for forgiveness, and never-to-be-kept promises to reform. Did anyone plan to romanticize abuse? No. It was the result of intrusive network officials. Damn the nature of the genre (of which they were and remain oblivious); they liked boys’ stories.

Soap opera has been slowly but relentlessly abandoned by the majority of the millions of women who used to avidly await each new episode, to see what nothing else on American television, at the time, would give them: her story, taken seriously. But despite the subsequent catastrophic drop in ratings, the networks have not re-evaluated. The dominion of The Contrite Thug continues. Yes, of course, the lowered ratings can be attributed to the fact that so many women are now working outside of the home, but technology has made it possible to see one’s favorite shows at any convenient time, and indications are that a very few women are taking advantage of that. It is also true that women are now being spotlighted now on night time TV, as had not been the case, but loyalty to the daytime soaps would have prompted old time aficienados to find ways to see their favorite shows, if there was anything left to draw them to do so. There is not.

I cannot prove without a doubt that the primary reason that only a paltry million viewers, at most, still watch the four remaining soaps is that Thugs have usurped them. But since that is the big change within the genre, it seems likely. Women notoriously are willing to watch stories about men to whom they play second fiddle, but the Contrite Thugs lack appeal for the majority of old school soap fans. Soap opera, once the bastion of morality, ethics, and rigorous consequences for bad behavior, as well as of women’s stories, have been polluted by crime, immorality, and unethical behavior by men who are consumed with the desire to assert their macho control. That desire poses major problems for an endless story, and soap writers have had to figure out ways to keep the continued criminality of the Contrite Thugs from landing them in jail, and therefore useless to the show. This has meant almost laughably inane “violence interuptus.” For a while, mob boss Sonny Corinthos, who has never served time for his crimes, was repeatedly shown pointing a gun at someone’s head and just before pulling the trigger renegging. “But if you ever do that again…….” Cue an eye roll. It has also resulted in the articulation of reprehensible excuses for double dealing and racketeering, even for murder, mostly by the women characters whose stories have been taken away, and a reprehensible lenience of judges toward men like Sonny.

Thank God, that this is television and not real life. Imagine what America would be like if in reality known crooks and abusers were put into power positions while constantly being forgiven their crimes under the adoring eyes of indulgent, marginalized women, despite the obvious fact that their endless reprieves from the consequences of their actions are mere prologues to worse lawlessness.

Martha P. Nochimson’s 26 year career as a University Professor of film and literature is only part of her story. In addition to the pleasure she has taken at being in the classroom at Mercy College and the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, she has worked as an editor for Cineaste magazine, written for American television, and has had the privilege of being in long running conversations with both David Lynch (25 years and counting) and David Chase (ten years and counting). She has published six books and is about to start work on Inner Tube: Television Beyond Formula for the University of Texas Press.

Thanks so much for this. Fascinating account. UK soaps not quite at this point yet but who knows what will happen?

You are very welcome,Christine. I would like very much to hear about what’s happening with UK soaps. Perhaps at SCMS 2018? (I can’t be there this spring.)

Good article. I’m from the UK and was interested in what caused the decline of US soaps and when it happened. Was it mid 90s? As for the UK, EastEnders seems to be in a decline while Coronation Street and Emmerdale seem to be on a high and in fact have increased their ratings over the last few years. My favourite soap is the Australian show Neighbours which only survives through money it gets via its deal with a UK broadcaster.