Brian’s music taps into the same source that gospel music taps into. That deep, fundamental sadness or darkness that we all carry. It’s like it finds you there and it takes you up out of it. That was just innately in the music. The harmonies, the sound, offered a way out and a transcendence.

— Jim James, lead vocalist and guitarist for My Morning Jacket

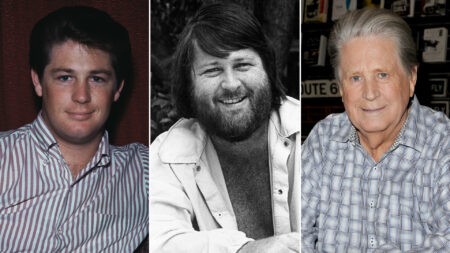

Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys were never as they seemed during the height of their popularity during the Sixties. The Wilson brothers in particular—Brian, Dennis, and Carl—grew up in a modest two-bedroom 900 square foot stucco house in the blue-collar South Bay town of Hawthorne, California. Their dad, Murry, was a machinist as well as an aspiring musician and songwriter. He shared his passion for music with his children even when they were toddlers.

Murry’s father had moved the Wilson family west from Kansas during the Twenties to nearby Inglewood. William ‘Buddy’ Wilson was a plumber and a heavy drinker who was often verbally and physically abusive with Murry and his other seven children. He thus passed this family dynamic down to Murry. Brian, Dennis, and Carl’s mother, Audree, was a housewife and an amateur pianist and organist. She was also an alcoholic. The Wilson home was not a happy one. Music was a love they shared and also their favorite means of escape.

The above observation by singer-songwriter, Jim James, is delivered onscreen in the final five minutes of ‘Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road.’ It speaks to the sad undercurrent of loneliness and alienation that is so identifiable in what appears to be the happy, carefree California sound that Brian pioneered with the Beach Boys. This band rapidly emerged as the preeminent American pop-rock group starting in 1961 through 1967.

Tuesday, June 14, at 9 p.m. ET, PBS’s 36-year-old multiple Emmy-award-winning flagship series, American Masters, devotes its 277th episode to Brian Wilson. Beginning on June 15 and thereafter, this 93-minute documentary can be accessed free online at https://pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/episodes/. American Masters is produced at WNET-Thirteen, which blankets the New York metropolitan area. The series’ episodes are later telecast on the Public Broadcasting Service’s core schedule to the network’s 330 affiliated stations and then made available without charge through streaming worldwide a day afterwards.

American Masters is ‘devoted to America’s greatest native-born and adopted artists,’ including biographical portraits of novelists, poets, dramatists, musicians, filmmakers, actors and actresses, visual and performing artists. As a rule, the subjects of these feature-length documentaries are either deceased or in the twilight of their career (as with Brian Wilson who turns 80 on 20 June 2022). The goal of the series is to situate the artist along with his or her career, work, and legacy into a larger longer-term framework of understanding.

‘Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road’ was produced, written, and directed by journeyman television producer and documentarist, Brent Wilson (who has no relation to Brian). It debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival on 15 June 2021. This documentary next enjoyed a brief art house theatrical run in the US and UK before being made available for purchase or rental on a number of commercial streaming sites such as Amazon Prime Video, Apple TV, and Vudu. Now PBS is releasing it for free worldwide consumption.

The most obvious and poignant takeaway in ‘Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road’ is voiced by singer-songwriter, musician, and record producer, Linda Perry, a mere four minutes into the episode when she addresses Brian Wilson’s mental state head on. ‘You know there’s something going on with Brian Wilson. There’s no hiding that this man is troubled and trying to escape something.’

Less than five minutes later, a title card further clarifies Perry’s initial disclosure: ‘At age 21, Brian began having auditory hallucinations — usually voices in his head telling him cruel and degrading things. Decades later, he would be diagnosed with a serious mental illness called schizoaffective disorder. Even with therapy and medication, the voices have not stopped.’ Brian Wilson’s somewhat withdrawn, halting, and emotionally flat onscreen behavior is therefore put into proper context for viewers.

His present-day demeanor and comportment contrasts greatly from what is evident in the stock and home movie footage that shows him with the other Beach Boys playfully interacting and making music in their teen years and early twenties. Brian was the quarterback on the Hawthorne High School football team, played baseball, ran cross-country, and had many friends. He was also the acknowledged leader and driving force behind the Beach Boys from the outset.

Schizoaffective disorder typically emerges in a person’s late teens or early adulthood and is caused by a constellation of interrelated factors including childhood trauma, stressful life events, and brain chemistry. As the Beach Boys’ first manager and music publisher, Murry could be overbearing and a relentless scold to his boys, beating them occasionally, especially Dennis and Brian. He once struck Brian in the head with a wooden board causing a permanent loss of hearing in his right ear. The Wilson brothers and cousin, Mike Love, finally reached a breaking point with Murry’s controlling and abusive behavior, firing him in early 1964.

This extraordinary level of family dysfunction in combination with the Beach Boys sudden fame and hectic life on the road, took a toll on Brian. Another title card updates the effects of his schizoaffective disorder at the 17½ minute mark of the episode: ‘In 1964, after suffering a panic attack on tour with the Beach Boys, Brian decided to stop touring and stay in Los Angeles to focus on writing and producing music. During this period, Brian wrote his masterwork, Pet Sounds.’

What popular memory in the 21st century forgets is that the Beatles biggest rival during the Sixties were the Beach Boys not the Rolling Stones. Even Brian Wilson was feeling that the Beach Boys High Fifties aesthetic of stripped candy-coloured shirts and chinos were going out of style by early 1965. He also began collaborating directly with the best Los Angeles-based session musicians informally known as the wrecking crew, rather than his usual bandmates who were out on the road touring nearly nonstop during the mid-Sixties.

California beach culture with its hot rods, surf shops, and Gidget-inspired Hawaiian luaus was just coming into its own when the Wilson brothers were in high school during the late Fifties. Their home in Hawthorne was only five minutes from Manhattan Beach; six miles from the sun-kissed white sands of Hermosa Beach; and seven miles from the breakwater of Redondo Beach. The best-looking brother, Dennis, was the only surfer, and he suggested to the rest of the Beach Boys that they infuse elements of the South Bay Southern California lifestyle that engulfed them into their music. The Pendletones thus became the Beach Boys in 1961.

Brian began to outgrow that identity when he stopped touring and began focusing exclusively on composing and producing. Between 1964 and 1967, he started experimenting with more progressive chord changes and complex orchestration; employing instruments never before associated with mid-20th century American popular music, such as French horns, flutes, chamber strings, and the Electro-Theremin. As Elton John observes in the documentary, Brian ‘had an orchestra in his head.’

In essence, Brian Wilson was mixing and matching the styles and influences of pop, rock, jazz, and classical music. Even before George Martin and the Beatles, Wilson was the first rock ‘n’ roll composer-producer to utilize the studio as an instrument. Musician, producer, and record executive, Don Was (née Don Fagenson), produced and directed a short feature-length documentary, Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times (1995), because he felt the obligation to explain to ‘non-musicians how sophisticated and complex and innovative his music is. And that really is why I made the movie.’

Brian Wilson has long been the musicians’ composer and producer. Today the public narrative about him has congealed into a classic three-act structure. Act I is played out in Was’ Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times, which delineates the musical genius of Brian Wilson while also introducing the conflicts caused by his mental illness along with the excessive self-medicated and prescribed drug taking that he used to manage his emerging symptoms including his more frequent and intense bouts of depression.

Act II—the moving middle—is the dramatic territory covered in Bill Pohlad’s biopic, Love & Mercy, which largely addresses Brian Wilson’s years in the wilderness (1983-1992) when he was under the legal guardianship of Dr. Eugene Landy, culminating in his court-ordered separation from the celebrity psychotherapist. Love & Mercy ends with Brian’s marriage in 1995 to his second and current wife, Melinda Ledbetter Wilson; and his completion of the long-abandoned Smile album in 2004.

Acts I and II are both briefly acknowledged in American Masters: ‘Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road.’ For example, Brian characterizes his time with Landy as ‘serving a nine year sentence’; and refers lovingly to marrying Melinda while also noting that they have since adopted five children over the intervening years.

Overall, though, ‘Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road’ is a realization of Act III—the resolution of the Brian Wilson story—portraying him as a survivor. The last shot of the documentary for instance is another title card that makes explicit that ‘Brian Wilson’s struggle with mental illness continues to be part of his daily life. Despite this, he continues to tour and record new music.’

Interestingly, Was’ documentary and Pohlad’s biopic are named after two well-known Brian Wilson songs, but American Masters: ‘Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road’ draws on Carl Wilson and Jack Rieley’s composition for its subtitle. Brent Wilson reveals that this decision was made with Brian’s blessing. It moreover suggests a secondary narrative arc of the documentary whereby Brian ruminates on the close bond and love he still feels for his late brothers—Dennis and Carl—along with several other musical collaborators who come up in the running conversation he has with Jason Fine.

American Masters: ‘Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road’ contains footage drawn for over 70 hours of interviews filmed over three weekends and conducted by Fine who has known Brian since 1995 or two years before he even began working at Rolling Stone as an associate editor. Brian Wilson is a notoriously bad interviewee, but he feels comfortable with Jason. The spine of the film is thus built around these two old friends just driving and talking, visiting Brian’s old haunts, and listening to Beach Boys music.

Time and again, it is apparent that Brian has a great deal of trouble putting his thoughts into words. What is revelatory, however, is his spontaneous reactions to the music and to what he and Jason are discussing. For example, Jason Fine offhandedly remarks that former disc jockey, songwriter, and record producer, Jack Rieley, who managed the Beach Boys from the summer of 1970 through the end of 1973, has died. Brian has no filter on his emotions in response.

American Masters: ‘Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road’ turns out to be a kind of buddy movie that provides an unguarded, unfiltered, and unstuck portrait of Brian Wilson in the present moment. He and Jason Fine do what people do when cruising the endless freeway system that crisscross Los Angeles. They drive around talking and listening to music. Like Brian’s musical legacy, this documentary is complicated, bittersweet, and ultimately redemptive. In the end, Brian Wilson’s songbook is a brave attempt to make joyous music, even when the composer-producer was sometimes struggling in the depths of despair.

Gary R. Edgerton is Professor of Creative Media and Entertainment at Butler University. He has published twelve books and more than ninety essays on a variety of television, film and culture topics in a wide assortment of books, scholarly journals, and encyclopedias. He also coedits the Journal of Popular Film and Television.

References

Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times (1995) LIVE Entertainment. Produced and directed by Don Was. 70 minutes.

Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road (2021) Screen Media and Universal Pictures. Ley Line Entertainment. Produced and Directed by Brent Wilson. 93 minutes; Television Premiere: American Masters: ‘Brian Wilson: Long Promised Road’ (14 June 2022) PBS/WNET.

Gidget (1959) Columbia Pictures. Produced by Lewis J. Rachmil. Directed by Paul Wendkos. 95 minutes.

Love & Mercy (2014) Lionsgate and Roadside Attractions. Battle Mountain Films and River Road Entertainment. Produced by Bill Pohlad, Claire Rudnick Polstein, and John Wells. Directed by Bill Pohlad. 121 minutes.

Wrecking Crew (2008) Magnolia Pictures. Produced and Directed by Denny Tedesco. 101 minutes.