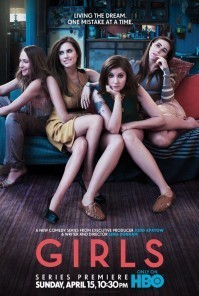

The US comedy Girls debuted on pay-cable channel HBO in April 2012 to viewing figures of less than 1 million (rising to 4 million with Video on Demand). Its media reception however belies such modest ratings as it became subject to widespread acclaim and criticism even before it aired. As discussed by Helen Wheatley in her recent CST blog ‘Loving Girls’, such attention resulted in her making a ‘rather conscious decision’ to follow Girls when it was broadcast on Sky Atlantic in the UK, as it not only allowed her to keep up with a show that everyone seems to be ‘talking/teaching/writing about’ but also fitted with her current project around ‘Television for Women’. Girls offered me something similar, namely a chance to reconnect with US comedy after a somewhat self-imposed period of abstinence following my doctoral thesis on US sitcoms in the post-network era (Williamson 2008a). Adopting an institutional approach, my thesis took the form of three case studies examining the sitcom output of broadcast network NBC, pay-cable channel HBO and niche-network UPN (which later merged with The WB channel to become The CW) and therefore included an analysis of Sex and the City (HBO, 1998-2004), with which Girls is regularly compared and contrasted. I suppose I was also concerned that I was no longer the target demographic and wouldn’t ‘get’ the show as my single, twenty-something days free of responsibilities are well and truly behind me, but that is another story (and indeed I enjoyed Sex and the City despite having never owned a pair of Manolo Blahnik’s). I needn’t have worried however as, like Wheatley, I also found myself ‘Loving Girls’. Yet, as its media reception suggests, the show is problematic and in particular raises issues around gender, privilege and race. What I would like to do here therefore is place it within an institutional context by first examining it in relation to HBO’s promotional strategy as offering something ‘other’ than network television. I will then draw what I believe to be a more useful comparison with another female-authored US sitcom Girlfriends (2000-2008), which attracted similar ratings to Girls yet remains largely invisible to white audiences and the mass media due to its explicit status as a ‘black’ sitcom through its presence on niche network UPN/The CW.

For its admirers then, Girls is a female-led comedy with a strong authorial voice in Lena Dunham, the creator, writer, executive producer, occasional director and star of the series. Unafraid to foreground her character Hannah’s complexities and questionable sexual experiences, Dunham also embraces her average body shape by consistently appearing either naked or in her underwear eating cupcakes. Indeed, when asked about her weight by her sort of on/off boyfriend Adam, Hannah replies, ‘No, I have not tried a lot to lose weight, because I decided I was going to have some other concerns in my life’. As described by Joy Press of the LA Times, ‘Dunham’s writing fills a gap felt by young women (and some men too) who’ve come of age with the Internet’s confessional overshare culture and long to see the messiness of their lives depicted naturalistically onscreen, whether dealing with sexual embarrassment, drug experimentation, body image issues or career screw-ups’. Or, put more succinctly by New York Magazine’s Willa Paskin (quoted in Nussbaum), ‘the show felt, to her peers, FUBU: “for us by us”’.

Its critics on the other hand have drawn attention to what the series does not feature, namely central characters of differing social backgrounds or racial heritage. This lack of diversity raises issues for many viewers attracted to Dunham’s individual voice and agency. For example, Kendra James wrote a Racialicious article entitled ‘Dear Lena Dunham, I exist’ which responded to Paskin’s ‘for us, by us’ quote by asking ‘but which “us” are you talking about?’ Likewise, Jenna Wortham, explains: ‘The problem with Girls is that while the show reaches – and succeeds, in many ways – to show female characters that are not caricatures, it feels alienating, a party of four engineered to appeal to a very specific subset of the television viewing audience, when the show has the potential to be so much bigger than that.’ Naming the show Girls implies a universal quality but the experience rendered onscreen is actually that of privileged, white girls, with the show focusing on what Emily Nussbaum describes as ‘women who are quite demographically specific – cosseted white New Yorkers from educated backgrounds’.

This air of privilege is nothing new however within the realm of HBO programming and indeed can be understood as part of a wider promotional strategy encapsulated in the slogan It’s Not TV. It’s HBO. As Marc Leverette (2008: 125) argues, ‘while often discussed in terms of “quality” or being a “premium brand”, HBO’s marketing and clientele clearly smack of a kind of elitism and exclusion’, and I have outlined elsewhere (Williamson 2008b) the ways in which, as a pay-cable channel, HBO maintains its differentiated status within the marketplace by positioning itself as a prestige product worthy of a monthly fee. In terms of its comedic tradition, HBO programmes often revolve around elite or exclusive groups, all white of course, such as the fashionable New York lifestyle depicted in Sex and the City, the young Hollywood A-lister and friends in Entourage (2004-11), showing us behind-the-scenes of a successful talk show in The Larry Sanders Show (1992-98), and the privileged lifestyle of one Larry David in Curb Your Enthusiasm (2000-), the creator of Seinfeld (NBC, 1989-1998) whose personal wealth is described in one episode of Curb as being $475 million, a figure that has almost doubled since.

It is the comparisons with Curb that I am most interested in, although I don’t have too much space to consider them here, and the ways in which David, playing a version of himself (i.e., an independently wealthy man), lives a rarefied existence in which the rules of society do not seem to apply to him. Hannah does something similar, although the fact that she has her rent paid by her parents hardly places her in the same wealth bracket. As a self-absorbed twenty-something with numerous neuroses however, she seems, like David, to have no filter, such as when she sabotages a job interview with an inappropriate date rape joke. Yet, the character of Hannah and Dunham herself have been criticised in ways that David has not. So what differentiates Girls from Curb Your Enthusiasm and indeed the other HBO comedies mentioned? It is, of course, that it has a female author in an era in which Quality TV has become synonymous with ‘masculinity’. This is highlighted by Amanda Marcotte in her 2011 article, ‘How to make a critically acclaimed TV show about masculinity’. Citing The Wire (HBO, 2002-08), The Sopranos (HBO, 1999-2007), Mad Men (AMC, 2007-) and Breaking Bad (AMC, 2008-) as top-tier examples, Marcotte argues, ‘the irony is that these new shows about men mine territory familiar to feminism, and could even be described in many cases as explicitly feminist. But for all the feminism on TV, high quality dramas about women haven’t taken off’. To an extent this has began to change, with dramas such as Scandal (ABC, 2012-) and Nashville (ABC, 2012-) and numerous comedies with ‘girl’ in the title, but what Marcotte doesn’t explicitly state, although is no doubt aware, is that quality TV tends to be authored by white, middle-aged men and it is the same demographic who are the gatekeepers of TV in general. Again, there has been an influx of women of late, with Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, Liz Merriweather, Shonda Rhimes, Mindy Kaling, Callie Khouri and, of course, Lena Dunham, but it seems that with so few female authors, programmes like Girls face criticism for not representing a more diverse range of voices.

One of those voices is Mara Brock Akil, the creator of Girlfriends which debuted on UPN in 2000. When Girls first came to public attention, the obvious comparison was with Sex and the City, which the show itself acknowledges. But its title and the subsequent debate around race made me also think of Girlfriends, which was pitched to network execs and referred to within media discourse as a ‘Black’ Sex and the City. That they are both female-authored with a female-led cast is something that, as I just mentioned, is still rare within US television and that Brock Akil is also black is even rarer. In his discussion of what he describes as the ‘raced processes’ involved in the commissioning of network television, Darnell Hunt (2005: 17) explains that it is white males who have ‘traditionally occupied nearly all of the industry “green-lighting” positions’ while ‘white executive producers or “showrunners” have a stranglehold on the development and day-to-day creation of television programs’. Again, this has gradually began to change, with regards to the latter point at least, due to the fragmentation of the broadcasting landscape that has resulted in the existence of niche networks such as UPN/The CW and cable channels such as BET (Black Entertainment Television). Targeting young, ethnic audiences who are traditionally underserved by the major networks, these niche networks open up the industry to black and ethnic writers, directors and producers who had previously been restricted to lesser roles on primarily white programming. By providing a (limited) platform for the production of black programming, these operators have helped to facilitate the participation of non-white groups within the industry, albeit on a small scale.

It is in relation to the character types represented that Girlfriends differs greatly from Girls however. Both shows explore relationships based on friendship and work rather than family ties but while the characters in Girls may have wildly divergent personalities, they inhabit a very similar social milieu. Girlfriends, on the other hand, takes the opportunity to present four characters that are also distinct from one another in terms of social background and racial heritage. Thus we have Joan, the level-headed and reliable attorney who serves as a point of identification for the both the viewers and other characters in the show, and her childhood friend Toni, a successful real-estate agent with a penchant for designer labels. Despite possessing the means to be economically independent, Toni judges each potential boyfriend according to their wealth and eventually marries a white Jewish doctor. This places her in contrast to married mother-of one Maya, who works as Joan’s assistant. With her husband Darnell employed as a baggage handler and Maya having dropped out of school on becoming a teenage mother, Toni consistently draws attention to her lower social status and her black speech patterns. The character of Lynn makes up the central foursome and is the least easily categorised. Holding a number of postgraduate degrees and positioned as an eternal student, Lynn is the only biracial character in the show, having been born to a black father and white mother before being adopted by a white couple at birth. Her biracial status means that the notion of racial difference is constantly present within the fictional world that the four friends inhabit and it also sets her apart somewhat from the other black characters.

I don’t have space to consider this in more detail, except to say that, unlike Girls, Girlfriends makes visible the concept of ‘otherness’ and attempts to avoid depicting the black community as monolithic. Moreover, while this may indicate a degree of racial and ethnic integration within the show, the relationships are not free of complexities. As such, it adopts what Herman Gray (1995: 90) terms a ‘discourse of multiculturalism and diversity’ and engages with the cultural politics of difference: ‘Television programmes operating within this discursive space position viewers, regardless of race, class or gender location, to participate in black experiences from multiple subject positions. In these shows viewers encounter complex, even contradictory, perspectives and representations of black life in America. The guiding sensibility is neither integrationist nor pluralist, though elements of both may turn up.’ Perhaps Dunham and HBO could do something similar.

Lisa W Kelly is a Research Associate at the Centre for Cultural Policy Research at the University of Glasgow. Her research includes work on television sitcom, particularly within the post-network era, and business entertainment formats such as The Apprentice and Dragons’ Den. She is co-author (with Raymond Boyle) of The Television Entrepreneurs: Social Change and Public Understanding of Business (Ashgate, 2012) and is currently part of an AHRC-funded project examining film policy and the history of the UK Film Council.