I was asked to write an op-ed piece saying why I think the BBC’s Written Archives Centre (WAC) is a unique and brilliant resource, which I can do because it’s both – and why, therefore, the BBC’s slimming of its services is a Bad Thing.

But what point preaching to the converted – writing the words of a sermon that no one (who can halt it) will hear?

So this, instead, is written for the people executing the changes, who’ve met every valid protest with a standard rebuttal that asserts the less-is-more theory in pacifying management-speak.

At the moment, you have most visibly introduced two restrictions.

- You’ve banned non-professionals from going there. No longer can research be done by people on a personal-interest mission, perhaps to publish their findings online – your new stipulation being that access to WAC is given only to researchers affiliated to a university or a book publisher … no matter that public money has paid for everything in the archive.

- The second restriction is on ‘file vetting’ – denying users access to files not previously consulted. You’ve a rationale for this but demonstrably it’s not one that could be branded sensible, being implemented against the wishes of the staff (who’ve always vetted files in appreciation of its necessity) and throwing an infuriating and maddeningly random spoke into so many academic and artistic research assignments without even leave to appeal.

Both those restrictions can be explained away, but we’re all grown-ups ups here: we all know these are very likely the wedge’s thin end, the first visible steps in a reductive process. Once these cutbacks have become the norm further restrictions can follow with less and perhaps ultimately no protest. You’ll hold the sander. These changes represent the accursed one-way run down Erosion Street.

And so I say to you BBC 2025 management types, you people doing this really-a-bit-brutal cultural squashing: do you know the BBC’s Written Archives Centre? Except perhaps when on fact-finding missions (justification sought for decisions already desired) have you been there? If not, I ask you to spend a couple of days in the place (Caversham is nice-enough, down by the Thames) and learn for yourselves just how exceptional this mistakenly undervalued resource is. Talk to the people, enjoy pursuing a research task for your own personal pleasure – and then pause.

Because I’m telling you straight: the BBC’s Written Archives Centre is a crown jewel of an archive.

BBC Written Archives Centre, Caversham

It’s a resource that any responsibly-managed body/authority should be proud to uphold and promote. In today’s ugly angry world, WAC is a soulful and enriching place of learning, a precious institution with a billion microfibres of Britain’s history. It’s the motherlode of all 20th-century archives, packing the richest tapestry of our nation and our way of life, together with much spectacular global content.

WAC encapsulates, in an infinite number of ways, when and how the BBC really was great – and perhaps shows how it can be so again, but differently. For the BBC’s Written Archives Centre has ultra-rich documentary material for –

- 80 years of every single day of the Home Service and Radio 4

- 80 years of serious music content on the Third and Radio 3

- 80 years of the Light Programme and Radio 2

- 60 years (close on) of Radio 1

- 20 years of each of the national and regional radio stations before those changes were introduced in 1946

- 100 years of regional broadcasting, and 60 years of local radio, separate stations so excellently covering their region throughout the UK

- 100 years of relaying royal and state events to the masses

- 100 years of radio and television drama – including the script of every play

- 100 years of breaking news and current affairs, of journalism, features, documentaries, talks, speeches, debates and interviews

- 100 years of political reports and parliamentary coverage

- 100 years of sports coverage

- 100 years of science and technological development

- 100 years of the complete panoply of light entertainment

- 100 years of arts programming – dance, painting, poetry, music for every conceivable kind of sound from and beyond orchestras to hip-hop

- 100 years of religious broadcasting

- 100 years of weather reports

- Decades of programming for minorities of all kinds, for ethnic diversities, the disabled and disadvantaged

- Nearly 100 years of global broadcasting and international co-operation

- 100 years of programmes for the young, the old, the infirm

- 100 years of schools broadcasting

- 60 years (near enough) of the Open University

- 90 years of Britain’s premier television channel

- 60+ years of BBC2 and decades of the other BBC TV channels …

All producing the world-enviable widest possible variety and most respected of programming for 365 days a year for all those years – plus it has, in filing systems robust enough to withstand a century of change, shoals of papers on great engineering projects, mountains of daily global minutiae from BBC Monitoring and files galore about policy and planning and people … and all this can be multiplied, because historical programming has caused producers to delve back thousands of years in their research (think BBC2’s Civilisation) and their deep knowledge is also within these actually limitless files.

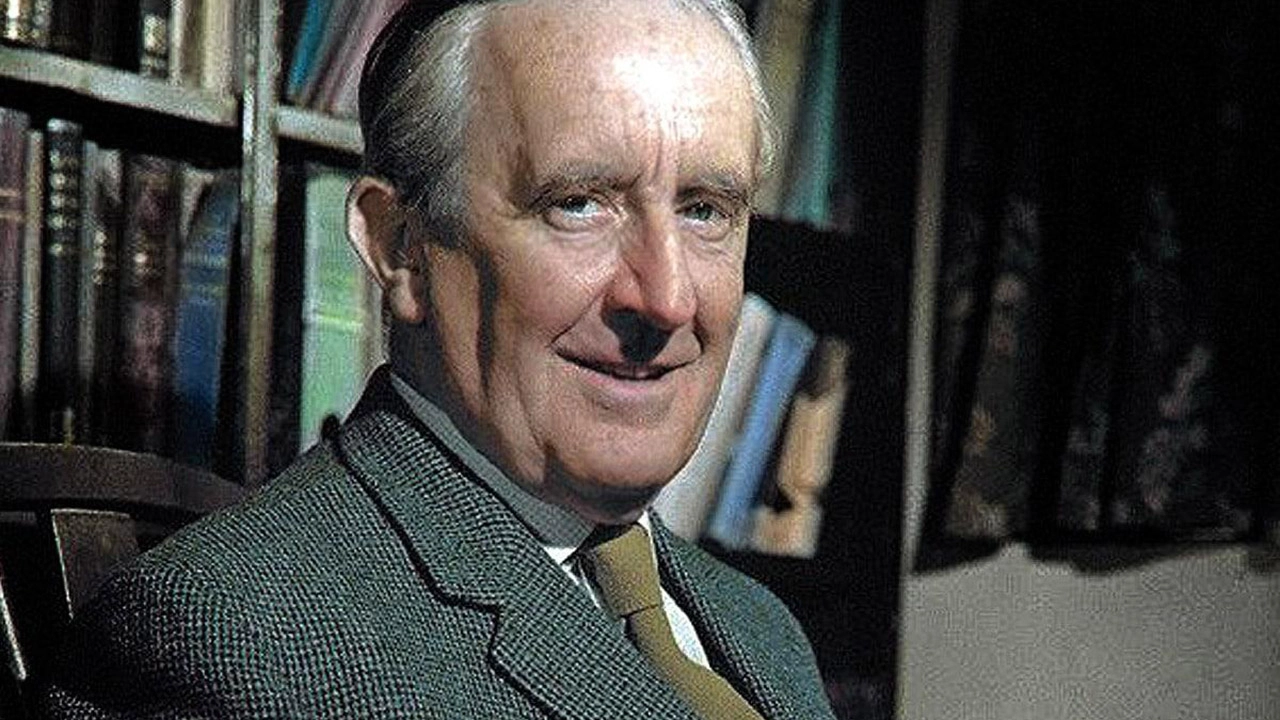

Not a word of that is exaggerated. There actually is voluminous paperwork for ALL OF IT. Here’s just one quick example of why WAC is great (and why every user will have their own personal stories). When I was last there, in May 2025, I requested a particular file and was, quite unexpectedly, thrilled to be handling the original transcript of a long talk by Tolkien. The producer of a BBC2 arts programme in 1968 had written asking for an interview, Tolkien said yes, and here, still on the file, is the original transcript typed on paper by a skilled secretary six decades ago. A few minutes of the man speaking was broadcast by BBC2 but that programme’s production file contains the whole long interview – what a wonderful thing! And yet, BBC 2025 management people, by your own absurd new constraints, I was fortunate that someone else had requested the file before me or it would be closed. And so right here we see why unfettered and independent access to the WAC resources is vital, and why, definitively, restrictions on ‘file vetting’ requests are harmful to learning, curtailing discovery.

J.R.R. Tolkien

Tolkien’s transcript is at the Written Archives Centre because the paper trail for all BBC output is here: the planning, the thinking and the legal necessities, the dedicated, intelligent work of many tens of thousands of employees in every field, and it can all be enjoyed through the contracts, contacts and personal correspondence of –

- The greatest playwrights of every generation for more than a century (and every lesser playwright as well)

- The greatest composers and conductors of every generation,

- The greatest musicians of every generation

- The greatest artists of every generation

- The greatest poets of every generation

- The greatest scientists of every generation

- The greatest documentarians of every generation

- The greatest orators and philosophers of every generation

- The greatest politicians of every generation

- The greatest administrators of every generation

- The greatest actors of every generation

- The greatest comedians of every generation.

Manifestly, a resource that has all of this must be supported to thriving point. I mean, you really cannot argue with that.

Instead, and no matter the positive words chiselled to explain it, the so-called 2025-implemented ‘model of access’ is a mean-spirited short-sighted policy that ought to and maybe does contravene the spirit of your job description. And when in another one/three/five years your BBC tenure is over and you’ve moved on to some other elevated post for your impressive CV, the phenomenal learning resources at WAC – recording the history of the British people through its public-funded structures – will be reduced, denuded by your legacy, forced into a thinner existence that smites its history and its future and all the people who rely on it for an infinite variety of reasons you can’t begin to know about.

So how about making some changes instead? How about embracing a bold new concept for the place – fresh ideas which, when lauded in the future, will undoubtedly cast you as a VISIONARY, a WINNER.

First and foremost is to let WAC prosper: Let a board of trustees be formed to ensure decisions on its direction are taken solely in its best interests by the people who cherish its content and will do their damnedest to ensure its well-being and longevity.

And maybe WAC could have its own creative marque, its own authorial imprint. This resource can become the well-spring to countless creative ideas, for projects from village to Hollywood productions; give it a healthy chance of delivering a unifying uplift and cohesion to communities throughout Britain. Let WAC’s gold seams stimulate creativity for commercial gain and also, always, for non-monetised enrichment in both academic and non-professional fields. (And this – today’s world compels me to say – is an entirely apolitical notion.)

In short, let WAC’s awe-inspiring collection be allowed to uphold the far-sighted principle with which it was gathered, the imperative that has graced the BBC’s coat-of-arms since its coining 98 years ago (1927) and to which its every passing employee owes dutiful respect: Let nation speak peace unto nation.

Mark Lewisohn is a historian.