The US science fiction adventure series The Time Tunnel (1966-7) is about television. It’s about the capabilities of the medium, its technologies and the experience of watching it. The series has a grandiose, excessive visual style, characterised by scale and spectacle, and it served to advertise colour television as colour sets became more affordable in the 1960s. The first episode introduces a massive underground base, hidden beneath a desert, in which the secret Time Tunnel device is being built. The Tunnel is a portal through which the protagonists Tony and Doug can travel to any moment in the past or the future, though without control over where they end up. I would argue, then, that the Tunnel is a metaphor for television (Bignell, 2022). Like TV, it can transport us to real or imagined places and times and engage us in thrilling narratives of exploration and peril.

The Time Tunnel was created by television and film producer Irwin Allen, who specialised in adventure series set in fantastic locations (De Los Santos, 2009). His career began with the film The Sea Around Us (1953), featuring extensive underwater cinematography, which he wrote and produced. He made the dinosaur fantasy The Lost World in 1960 and co-wrote, produced and directed the science fiction submarine film Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1961) before adapting it into a television series for ABC (1964-8). He created Lost in Space for CBS (1965-8), and later he produced the effects-heavy disaster movies The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and Towering Inferno (1974).

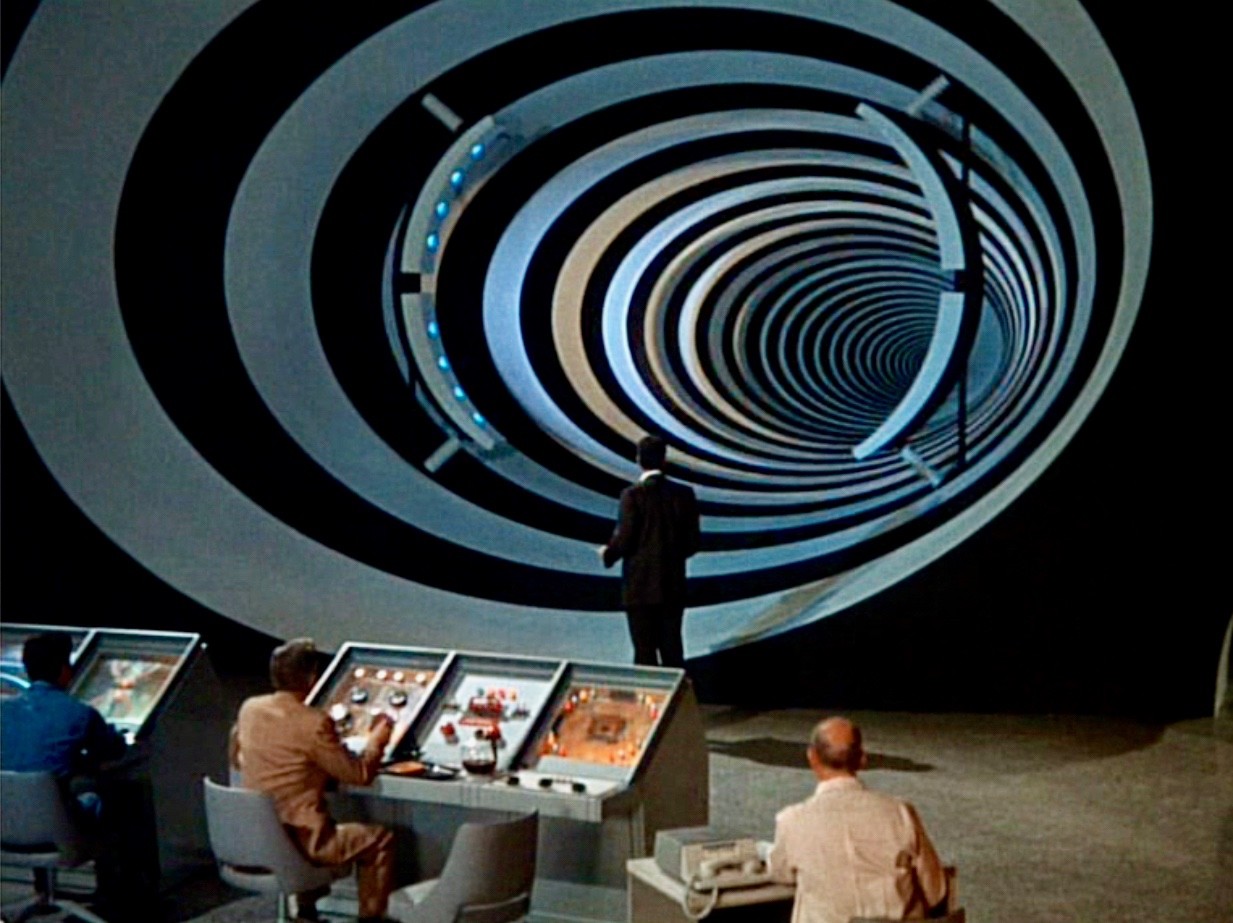

Allen’s production company invested the then huge sum of $22,500 into the Time Tunnel set (Figure 1), built across two adjoining soundstages at 20th Century Fox studios in Hollywood (Grams, 2012). But the grandiose and expansive look of the series was also underpinned by cost-effective procedures like using trompe-l’oeil paintings (mattes) to place actors and real props into apparently gigantic backdrops and incorporating footage cut from cinema films into the TV episodes. Trailers for The Time Tunnel featured a montage of clips of Viking warriors, Napoleonic soldiers and silver-suited futuristic aliens, as an announcer exclaimed: ‘You can be inside the first rocket to Mars … or inside the Trojan Horse. See the discovery of a new planet … or the discovery of fire. For the vast spectrum of time is revealed when two daring scientists are cast adrift in the fourth dimension – time!’ Scripts were written to fit library footage from Hollywood westerns, historical epics and science fiction films, and were oriented around thrilling visual revelations that could be cheaply achieved. While The Time Tunnel is ambitious television, its ingenuity shows us how producers like Allen coped with the gruelling constraints of studio production.

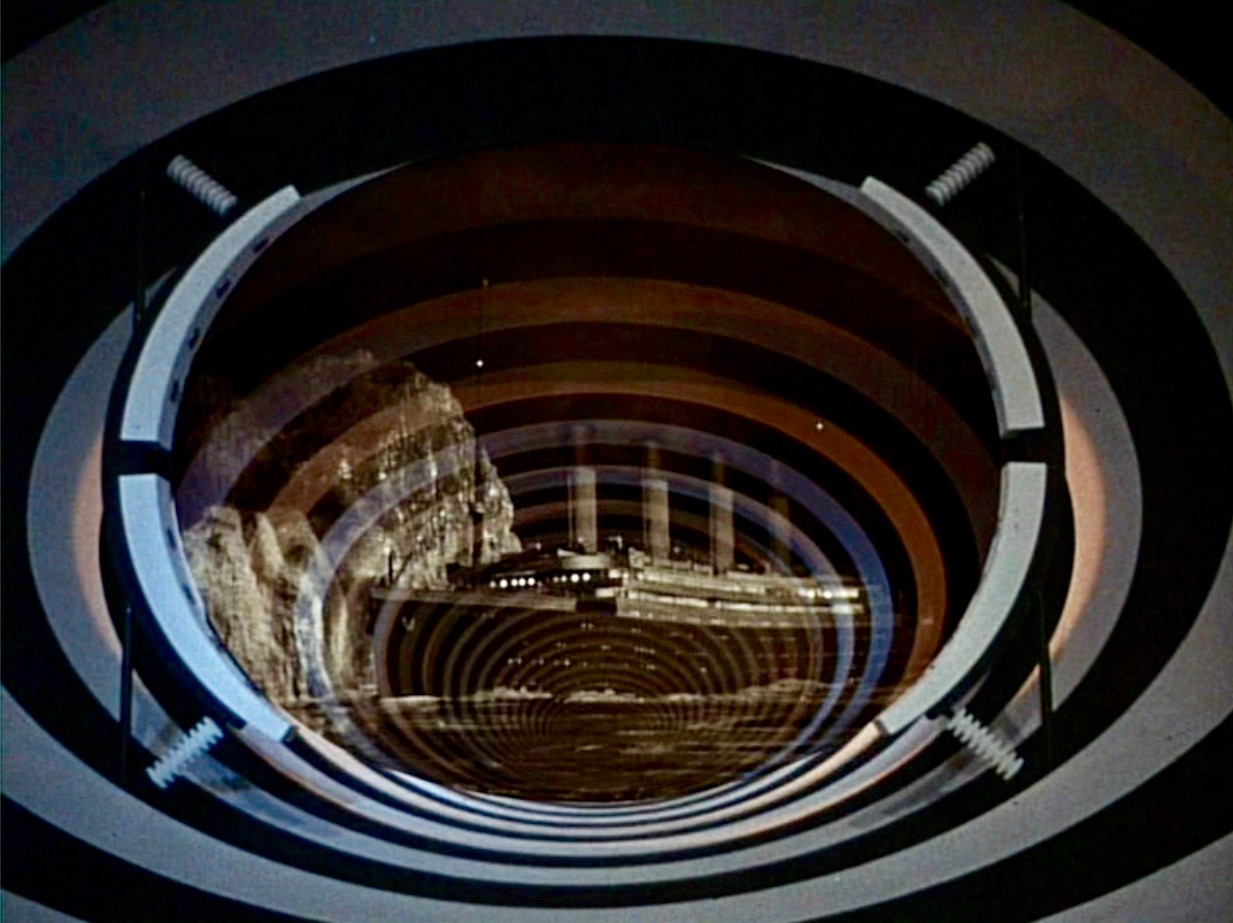

The key battleground for competition between the US networks at the time was colour broadcasting, and The Time Tunnel was designed to draw young, upmarket, urban audiences to ABC’s colour programmes (Alvey, 1997). The network had also made The Addams Family (1964-6) and Bewitched (1964-72), for example, for that audience. One of The Time Tunnel’s scientist protagonists, Tony Newman, was played by the pop star James Darren, while the other, Doug Phillips, was played by Robert Colbert who was well-known from ABC’s television Western Maverick (1957-62). Allen appointed the Oscar and Emmy-winning cinematographer Winton Hoch to work on The Time Tunnel; he had been a colour specialist on Technicolor’s filming process and would mastermind the integration of special effects and models made by L.B. Abbott, already winner of three Emmy awards. The Time Tunnel’s first episode, ‘Rendezvous with Yesterday’, transported the two main characters back to the ocean liner Titanic in 1912, just as it was about to sink. Action sequences were borrowed from the 1953 black-and-white film Titanic and tinted into colour. Our heroes eventually rescued an attractive English aristocrat played by Susan Hampshire, and the series often had famous guest stars to increase its appeal.

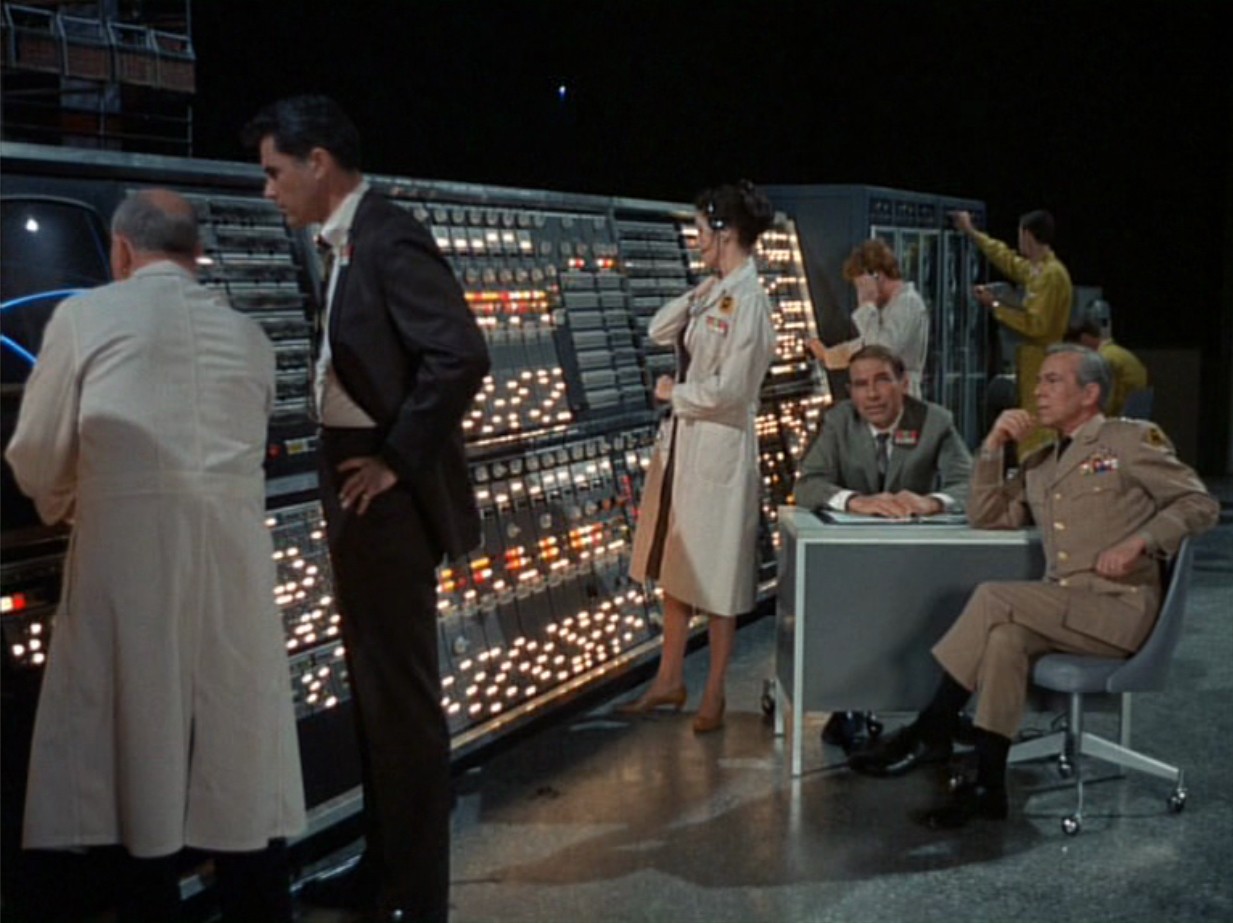

The Time Tunnel itself looks like a giant cathode ray tube from the interior of a huge television set. Its black and white concentric rings reference the paintwork on NASA’s experimental rockets, and the computer banks and consoles used in the Tunnel control room were supplied by a military contractor, Mars Aviation, and by the US Air Force, so they look very much like Mission Control in television news coverage of the Apollo space programme (Figure 2). It all looks contemporary, high-tech and scientific, as seen on TV.

Doug’s and Tony’s experience of travel in time is predominantly visual, but one of the attractions of The Time Tunnel is that they physically enter each different time period they visit. They stop and walk around the realistic medieval castles, prehistoric jungles and Western towns built at Fox studios. The Time Tunnel visited famous heroes and villains, events like the Gettysburg Address or disasters like the Titanic’s sinking. In addition to the Tunnel set, Allen used standing sets on the Fox backlot and locations in the Los Angeles region including a movie ranch, to create very different environments. Through the agency of the protagonists the television viewer also becomes a flaneur (a stroller or tourist) like Doug and Tony, transported to elsewhere and elsewhen, just as television offers its viewers a window on the worlds beyond their own experience.

Doug and Tony can be seen aboard the Titanic from the Time Tunnel base, thanks to the Tunnel’s ‘viewing area’. It shows images of the Titanic displayed across the mouth of the Tunnel (Figure 3) as if on a huge television. The scientists at the base watch the liner moving across the dark sea towards glistening ice cliffs. Chunks of ice fall onto the deck of the ship, and torrents of water flood into the fractured hull. The Tunnel scientists freeze Doug and Tony in time, represented by a freeze frame on the visualisation screen, and they are jerked away from the Titanic just in time, to a new setting that advertises the next week’s episode: inside a rocket to Mars.

ABC drummed up interest in The Time Tunnel among young adults by screening ‘Rendezvous with Yesterday’ at the 24th World Science Fiction Convention in Cleveland, Ohio in 1966. The pilot of Star Trek (1966-9), also being introduced there by its creator Gene Roddenberry, received a relatively sympathetic reception. The Time Tunnel was generally considered implausible but was subsequently given favourable reviews by science fiction writers. ABC scheduled The Time Tunnel at 7.00 pm on Friday evenings, which made it hard for the series to find an audience since younger viewers were likely to be away from home at that time. The series ran for thirty episodes, before head-to-head competition with NBC’s The Man from UNCLE (1964-8) and Wild, Wild West (1965-9) on CBS eroded its ratings. It did well in syndication in the USA and in export sales to the UK, Japan and Australia, however, and has proved to be relatively enduring.

The Time Tunnel drew attention to its futuristic technologies and past and future settings through its audio-visual style. Television has been characterised as a medium with low density of visual information, without style or spectacle, but in contrast, The Time Tunnel is self-consciously excessive. It can be stylistically innovative, paradoxically, because of its borrowings from other TV science fiction, from epic cinema genres and allusions to TV coverage of the US space programme. The Time Tunnel’s production team aimed for the visual emphasis that cinema was reputed to do better than television and planned from the start to borrow and exploit sequences from cinema films. Yet they also aimed for the sense of immediacy, familiarity and closeness to the action that is associated with series television. Such series had to be made on a restricted budget, so time travel had to be domesticated, like the television technologies in the homes of its audiences, while also offering the thrill of the new, alien or uncanny. The Time Tunnel aimed for fantastical, surprising wonderment, but was made possible by inventive uses of the available studio settings and practical effects. The Time Tunnel had to be new but also familiar, ambitious but also inexpensive, like US television entertainment in general, and it offered virtual travel to exotic and exciting places and times, as television does. It was, in a way, a celebration of TV.

Jonathan Bignell is Professor of Television and Film at the University of Reading. Some of his work is available free online from his university web page or from his academia.edu page. This blog derives from his much longer analysis of The Time Tunnel for the book Substance / Style: Moments in Television (2022) which he co-edited with Sarah Cardwell and Lucy Fife Donaldson. Jonathan’s writing often combines historiographic work with analysis of the audio-visual style of TV programmes and films. His most recent books are Beckett’s Afterlives: Adaptation, Remediation, Appropriation (co-edited with Anna McMullan and Pim Verhulst, 2023), and another book for the Moments series, co-edited with Sarah Cardwell and Lucy Fife Donaldson, Epic / Everyday: Moments in Television (2023) in which he writes about the 1965 Doctor Who story ‘The Chase’.

References

Alvey, Mark (1997) ‘The independents: rethinking the television studio system’, in Lynn Spigel and Michael Curtin (eds) The Revolution Wasn’t Televised: Sixties Television and Social Conflict. London: Routledge, pp.139-58.

Bignell, Jonathan (2022), ‘Grand designs: television, style and substance in The Time Tunnel’, in Sarah Cardwell, Jonathan Bignell and Lucy Fife Donaldson (eds), Substance / Style: Moments in Television. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 202-24.

De Los Santos, Oscar (2009) ‘Irwin Allen’s recycled monsters and escapist voyages’, in Lincoln Geraghty (ed.) Channeling the Future: Essays on Science Fiction and Fantasy Television. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, pp. 25-40.

Grams, Martin (2012) The Time Tunnel: A History of the Television Program. Duncan, OK: Bear Manor.