The first month of the new year, as has been the case now since 2012, heralds the start of another new series of the BBC’s flagship and consistently highly rated Sunday night drama of community nursing, midwifery and medicine Call the Midwife. Promos and advance publicity for the seventh series have primed audiences for the introduction to the regularly recurring cast of characters of a nurse of colour, for the first time in its run.[1]

For six series and a clutch of Christmas specials Nonnatus House, the East London convent that houses the nurse midwives that make up the show’s principal cast, has been home to an interchangeable parade of white and largely middle class (or even upper class in the case of Miranda Hart’s Nurse ‘Chummy’ Browne, later Noakes) young women, up until the introductions of some noticeably more working class or underprivileged nurses. First, in the 2015 fourth series, with the introduction of Nurse Phyllis Crane (Linda Bassett), who grew up as the illegitimate child of a poverty stricken single mother, and later, in the 2017 sixth series of former Army nurse Valerie Dyer (Jennifer Kirby), a Poplar local recruited to the Nonnatus House team by Jenny Agutter’s Sister Julienne, from behind the bar of an East End pub.

Now, Nurse Lucille Anderson, who hails from the West Indies and is played by British actor Leonie Elliott – probably best known to CST Online readers for her role in the ‘Hated in the Nation’ installment of the 2016 series of Black Mirror – has been written into the series to intervene in the ubiquity of the whiteness that has heretofore characterised the transient population of Nonnatus House.

Call the Midwife has, since its inception as a television series, and as I have demonstrated elsewhere,[2] adhered to what Julia Hallam, in Nursing the Image, her foundational treatise on cultural mediations of nurses and their profession, calls the ‘Take Four Girls’ (referencing the advertising hook for a 1972 NHS nurses recruitment initiative) approach to representational configurations of the cultural identity formation of the ideal nurse as normatively young, white and middle class, but articulated through a thus politically disingenuous multiplicity of subjectivities, and via the laboured individuation of the four otherwise culturally homogenous nurses.[3]

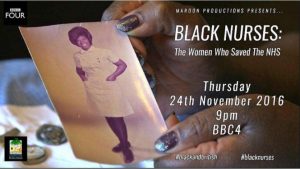

The historical reality is that contributions made to the delivery of NHS care by nurses in the formative post-war decades of the fledgling service by immigrant women’s labour (especially, at that time, from the West Indies, the Caribbean and the Philippines) are well-documented, not least by the BBC, which made an important intervention with the production and broadcast of the one-off documentary Black Nurses: The Women Who Saved the NHS as part of its ‘Black and British’ season in 2016, albeit one that shines a light on the representational absence of these women in nostalgic media fictions like Call the Midwife. Moreover, notwithstanding interventions like this, the contributions of these women are not, apparently, as well-known, understood or appreciated as they might be. As Hallam writes, “Public knowledge of black nurses’ experiences of recruitment and training in Britain remains scant.”[4]

As part of an address to the Radio Times & BFI Television Festival in June of 2017, Call the Midwife creator Heidi Thomas made clear the extent to which the introduction of Nurse Anderson as the show’s first regular nurse of colour was a conscious decision and a deliberate intervention into Call the Midwife’s status quo in which whiteness is a universal subject position for the regular cast of nurse midwife characters. Furthermore, she attributed this to new research she had undertaken into the historical realities of the NHS during the depicted period which, Thomas says, “has made me very aware of the contributions made by West Indian and Caribbean nurses to the NHS in the early 1960s.”[5]

Call the Midwife was lauded time and again by commentators in its early years as being paradigmatically feminist television,[6] and not without reason, on a number of apposite grounds. Over time though, questions started to be asked about the show’s adherence to normative paradigms in the depiction of its nurses, and whether its feminist credentials would stand up to scrutiny when viewed through an intersectional lens (they didn’t). Notwithstanding the introduction of queer characters engaged in a queer relationship in the 2015 fourth series (Emerald Fennell’s Patsy Mount and Kate Lamb’s Delia Busby), it nonetheless came under fire in some quarters for appearing to concede to the tedious inevitability of the so-called ‘lesbian death trope’ when at the close of their first series together, Delia is hit by a car. Although she survives the accident she is left with severe amnesia that viewers are invited, at the close of series 4, to understand has prematurely and tragically ended her closeted relationship with Patsy such that although she does not die, the two of them are nonetheless subject to the same kind of ‘symbolic annihilation’ that this trope enacts.[7] Writer Heidi Thomas was criticised in various parts of the media and public sphere for this storyline, especially coming as it did in the same year as another controversial lesbian death plot in Last Tango in Halifax.[8] The 2016 fifth series saw Delia make a miraculous recovery and it reunited her with Patsy. *Two full series later*, they even kissed on-screen once. Determining for sure whether or not there was a causal relationship between these phenomena would necessitate primary research beyond the scope of this piece. But one thing it certainly indicates is that Call the Midwife had form in making interventions into its status quo in service to the provision of a more intersectional representational landscape than the ‘Take Four Girls’ approach has historically allowed for.

It remains to be seen how the intervention made by the introduction of Nurse Anderson to Call the Midwife will manifest. But at a time when the present day NHS is losing the EU citizen nurses that are currently propping it up “in droves” and at a truly alarming rate,[9] the stakes involved in recognising and valuing the massive contribution made by immigrant labour to the viability of our health service in both the past and the present has never been higher. Notwithstanding the part that may or may not yet be played in the negotiation of the present day urgency of this situation through media fictions like the ones contrived (albeit through a historical lens) for this series, the sad reality is that it may well be too late for any public discourse to which it contributes to make any difference.

Hannah Hamad is Senior Lecturer in Media and Communication at Cardiff University, and the author of Postfeminism and Paternity in Contemporary US Film: Framing Fatherhood (New York and London: Routledge, 2014).

Footnotes

[1] http://www.radiotimes.com/news/2017-12-28/call-the-midwife-casts-leonie-elliott-as-new-west-indian-midwife/

[2] Hannah Hamad, ‘Contemporary Medical Television and Crisis in the NHS’, Critical Studies in Television, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp.136-150. DOI: 10.1177/1749602016645778

[3] Julia Hallam, Nursing the Image: Media, Culture and Professional Identity (London and New York: Routledge, 2000), p. 128-9.

[4] Hallam, p. 121.

[5] http://www.radiotimes.com/news/2017-04-09/call-the-midwife-to-introduce-new-west-indian-midwife-for-series-seven/

[6] Examples of commentators that hailed Call the Midwife as the ‘most feminist’ (or similar) show on television include, but are not limited to, Alison Graham of the Radio Times in 2013; Caitlin Moran of The Times in 2013; and Sabienna Bowman of Bustle in 2015.

[7] Liz Millward, Janice G. Dodd and Irene Fubara-Manual, Killing of the Lesbians: A Symbolic Annihilation on Film and Television (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017).

[8] Carrie Lyell, ‘Patsy and Delia Ride Again in Call the Midwife’, Diva, 13th March 2017, http://www.divamag.co.uk/Diva-Magazine/TV/Patsy-And-Delia-Ride-Again-In-Call-The-Midwife/.

[9] Denis Campbell, ‘European nurses and midwives leaving UK in droves since Brexit vote’, The Guardian, 2nd November 2017, https://theguardian.com/society/2017/nov/02/european-nurses-midwives-leaving-uk-nhs-brexit-vote.