One of the loveliest places that my wife and I like to visit when we have a spare morning or afternoon is Astley Book Farm. It’s the largest second-hand bookshop in the Midlands, and an ambling drive along some twisting country roads brings you to an entire farming estate where family, livestock and dairy have been expunged from the home and out-houses in favour of unimaginable quantities of Pan paperbacks from the 1950s, highly desirable collections of American newspaper comic strips and extensive academic works of vintage. All mouth-wateringly digested alongside some vibrant coffee’n’cake from a brilliant café.

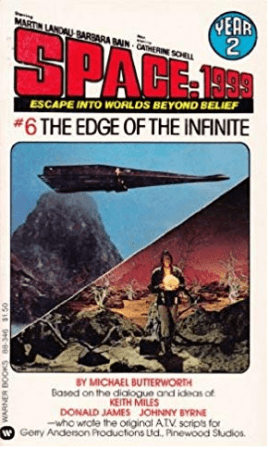

Last time we were there, we were amazed to find one of my own works being displayed to customers in one of the securely-locked glass cabinets located in close proximity to the counter. Amazed partly because putting it behind glass seemed to confer a status… a rarity… a value. I mean, Janet Grey’s Compact paperback from Icon Books was happily placed on the shelf. So was Michael Butterworth’s rare Space: 1999 #6: The Edge of the Infinite – only published in the US by Warner – in the SF section for a mere £2.75 [i]. So it really was amazing that my work was being given the accolade of being placed behind glass.

But what was amazing was that the volume under lock and key with my name on it wasn’t a book.

Understandable mistake. It looks like a book. It’s got pages covered in words like a book. The pages are all secured down the left hand side – western style – like a book. But it’s not a book. Well, not to my mind.

No matter how nicely bound, the 288 pages of The Prisoner: A complete production guide by Andrew Pixley are not really a book. A book is something which I’ve always believed should stand alone as an item in its own right. It should have a beginning, a middle and an end – and a sense of purpose. If it’s a book about a television series, it should explain to me why its subject matter is worthy of all this ink and paper in the first place, and then proceed to celebrate or analyse the programme in an entertaining and informative manner, building to some sort of conclusion. In the commercial world, I’d like opinion to celebrate whatever qualities have made the series so book-worthy. In the academic world, I’d like my understanding enhanced by an original argument or the sort that I’m incapable of writing myself.

Network started doing viewing notes that look like books with their DVD sets back in 2007. I’d done increasingly large sets of notes in booklet form for them and BBC Worldwide since 2004 – not just a single sheet folded into four pages with a cast list, but something meatier in terms of context and production background. But, like my ‘career’, the wordcounts got out of hand. “28,000 words! That’s half a novel! Better you than me,” exclaimed Alan Plater when sent the viewing notes on The Beiderbecke Affair and its sequels to forward to Big Al so that Big Al could write a foreword. When I hit almost 115,000 words on the revival of Danger Man (1964-1966), I feared that Network would simply reject it. Instead they said: “Fine – we’ll bind it like a book.”

So, why should I spent my time writing what seems to be a book but isn’t? Well, the volume behind the glass is a tragic figure – a sad divorcé, separated from its raison d’etre. You see, these are viewing notes – a text designed purely as appendices to the programme itself, packaged in a box of shiny discs containing the shows. The notes are designed to convey data and context – anything not immediately apparent when watching the series. And – as a lot of it is just data – the notion of reading it like a book doesn’t apply. It’s like settling down for the evening to read some logarithm tables for fun.

This is one of the strengths of companies like Network – they take chances on specialist stuff. And they support the notion of notes which pack in as much as possible. After all, why waste space on synopses of a programme you can watch? Or telling you why a show you’ve just spent money to view is any good – you spent the money, you already know that it’s good.

So, what do we offer? Suppose you’re watching the Man in a Suitcase (1967-1968) episode All That Glitters and wonder where that nice little village visited by McGill is? Look up the episode, it’ll tell you. Were these episodes of Pathfinders in Space (1960) live or pre-recorded? Check it out page 33. Do I recognise the DJ voice in the Public Eye (1965-1975) case The Man Who Didn’t Eat Sweets? Yes – production paperwork identifies uncredited roles and we’ve listed them. Why does Breakout feel like the end of the first colour run of Callan (1967-1972) but doesn’t air last? Chapter Five will sort you out. Did the BBC executives really hate Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969-1972) as much as is made out? Well, you can read David Attenborough’s comments at the board meeting of 16 December 1970 a quarter of the way through the Series B notes…

When it comes to explaining topical references, one needs to do so for a diverse readership of different ages, cultures and experiences who may not instantly know who Harold Wilson or Simon Dee were. And at times, I admit that the devilment gets into me when I’m explaining what seems instinctively obvious… but, hey, let’s do it just in case… [ii]

In addition to hard data like production dates (sometimes at day-by-day level) and untangling the web of regionalised ITV transmission dates, there’s other content which evokes unexpected responses from readers. The person who always remembered that music cue from an episode of Shoestring (1979-1980) and – because we identify the library tracks – has now tracked down a clean copy. A happy recollection from somebody who’s delighted that finally somebody has remembered how their ITV region didn’t take UFO on Saturdays like everyone else seemed to. Macho banter between Bodie and Doyle consigned to the cutting room floor of The Professionals (1977-1983) now fuels fan fiction debate for those captivated by the CI5 duo three decades later.

Furthermore, the last thing I want to do is to tell anyone what my opinions of an episode are lest I colour their viewing or enjoyment with my own worthless perspective. I’ll tell you how it was received at the time by Television Today or what viewers said about it in a BBC Audience Research Report or how many people watched it according to TAM… but, please, as to it artistic merits, you have the discs, and I think we can trust you to make your own minds up as to whether it’s any cop or not.

If these programmes are to be remembered and celebrated, they should be good enough to make a continual impact on those who see them and not need me to waste words explaining that they are good. That’s why I did feel a little bit worried at seeing the volume being offered for sale after being cut adrift from the discs that will allow the reader to make sense of it. Maybe it would be best to prevent somebody from spending money buying it. Or at least have a warning. Like you have with dangerous animals and chemicals.

Oh my goodness! That’s why it’s behind the glass!!

Andrew Pixley is a retired data developer. For the last 30 years he’s written about almost anything to do with television if people will pay him – and occasionally when they won’t. And what’s more he hates writing about himself in the third person because it makes him feel like an utter idiot [iii].

NOTES:

[i] Don’t bother phoning them… we bought that!

[ii] Actually, every so often it’s rather good fun to put in stuff that’s blatantly obvious or indeed blatantly wrong as a joke… just for those who are reading. Tend to do that for the comedy ones. Very naughty, and not the sort of thing that academics would approve of. But, y’know, it’s a grin.

[iii] Which, in all honesty, he probably is.