There are lots of ways to interpret and answer this deceptively simple question. Being asked what we make of something is often an idiomatic invitation to discuss how we think or feel about it. It invites a sharing of opinion and opens up a process of evaluation. In broad terms, who the ‘we’ is in this question determines what we make of the television archive. As an academic historian of television, and director of the Centre of Television Histories, it might be assumed that the ‘we’ in this question is me and other television historians. What this ‘we’ make of the television archive is fairly well-documented. In my work (Wheatley, 2007; Moseley and Wheatley, 2008) and in the work of others (e.g. Lacey, 2006; Jacobs, 2006; Messenger Davies, 2007; Wyver, 2017; Gorton and Garde Hansen, 2019), there has been a consistent acknowledgement of the vital importance of the television archive. For example, in drawing an analogy between the (largely inaccessible) archive of the BBC and a public library, the media historian John Wyver eloquently invites us to imagine the holdings of this television archive, the programmes contained within it, as an invaluable collection of books:

The books were created by many of the best and the brightest of the four nations, and they represent some of the very finest creative achievements by those nation’s greatest artists and thinkers and writers. They document what made the peoples of those nations laugh, what made them cry, what made them sad – angry — proud. As a consequence, the library and its books are – or would be, but for one little wrinkle – profoundly and immeasurably valuable to teachers, to school kids, to journalists, to artists, and to all those who want to understand who the peoples of the nations were and are – profoundly, immeasurably valuable indeed to each and every one of us.

Put this way, it is hard to argue with the drive to preserve, protect and make accessible this archive of ‘immeasurable value’. Academic historians have joined forces with equally passionate and committed groups of archivists and curators at the BBC and beyond, sometimes in the face of great indifference from those who control the key resources necessary to protect this invaluable national asset, to explore it and to protect it.

However, what a relatively small bunch of academics make of the television archive will not drive the proper investment in, and further development of, the television archive. We can write the most interesting and eloquent accounts about programmes that are held in the archive, describe them in beautiful detail, analyse them to construct detailed histories of programme policy, generic innovation, and individual artistry, but if we play no further part in making these programmes accessible for others to view, what we make of them can only take us so far. This is why a number of academic historians, including those of us based in the Centre for Television Histories, have focused their efforts on bringing archive programmes back to public attention in a variety of different contexts and for a variety of different audiences. This enables a much broader, and better informed, public to answer the question ‘What do we make of the television archive?’. We have seen this, for example, in John Hill, Lez Cooke and Billy Smart’s AHRC-funded project The History of Forgotten Television Drama which resurrected a number of important ‘forgotten’ programmes from the archive during its three year life span.

Whilst this project focused on revealing a history of significant programming to an audience largely made up of television aficionados or television history fans (through screenings at the BFI Southbank and Network DVD releases, for example), our own project, Ghost Town: Civic Television and the Haunting of Coventry, has sought to enable a (re)encountering of archive television for an entirely different group of people.The Ghost Town project is predicated on the fact that cities are haunted places: they are haunted by the ghosts of people, buildings, businesses, ideas, of things which once stood and now no longer remain. These traces of the haunted city might be slowly lost to the passing of time, but the city is also vividly recalled in another haunted place: the television archive. Throughout the lifespan of this project, we have been organising screenings of archive television around the city of Coventry leading up to and into its City of Culture year in 2021. We have worked with specific groups in the city, as well as a broader public audience, talking to people about the city through the television archive, and about the importance of the television archive through an engagement with the city’s history. These are not necessarily encounters of recollection for all people: for some, newly arrived in the city, it’s a chance to encounter the past lives of the place they now call home, or are just visiting. Ultimately, the intention is that our research will produce a kind of ‘test case’ for thinking about the relationship between television archives and particular places. Our project is very Coventry focused at the moment, but we seek to reveal how television archives can play a vital role in memory work, in civic place making and in the broader cultural strategies of diverse cities around the world. As Kristyn Gorton and Jo Garde-Hansen acknowledge in their recent book ‘[All] television memories are really anchored in and around places, people, spaces and buildings, homes (and their interiors), as well as clearly defined networks, organizational relationships, and professional and familial identities’ (2019: xii). We’re asking what this means for a city, using the television archive to inspire conversations, thought and action about the city’s past, present, and future, alongside making a case for the ongoing importance of the archive itself, and for the need for increased and easier public access to it; in essence asking the people attending our screenings and events what they make of the television archive.

Ghost Town obviously speaks quite directly to the impact agenda that is so significant in the UK HE context, but it also comes from a personal desire to take television history beyond the academy. I have never really been interested in doing work on archival treasures that only I have, or will, ever see, beyond their initial broadcast. Bringing programmes out of the archive is more important to me than getting into an archive to see them. This takes me back to work I did for my edited collection Re-Viewing Television History: Critical Issues in Television Historiography (2007). Re-reading the introduction to this book, I realised that in it I’m basically trying to confront the question of why television history matters, why we should bother doing it, why we should make anything of the television archive at all. In answering this question, I go back to John Corner’s ‘utilitarian defence’ of history, in which he argues: ‘An enriched sense of “then” produces, in its differences and commonalities combined, a stronger, imaginative and analytically energised sense of now’ (2003, 275). Here Corner is talking about television, and the need to know the medium’s history to better understand how it functions in the contemporary moment. However, we might also say the same of the history of a city, and certainly public understanding of that history, whereby an engagement with the city’s past via the television archive brings about ‘a stronger, imaginative and analytically energised sense of [the city] now’.

During the life of this project we have organised a series of screenings, exhibitions and events for the people of Coventry: these have included a week-long exhibition at the Shopfront Theatre, at which we employed multiple research techniques to gather data, including surveys, feedback postcards, participant observation (field notes), and semi structured interviews. We made cups of tea and chatted to people, creating an environment in which people could stay and talk to us and each other, in order to fully understand how people were engaging with archival television and the history of the city. We ran a series of memory and outreach workshops at this exhibition (from one aimed at a self-selecting memory/local history group, to work with schools’ groups and women from a local charity, FWT, that works with refugees, migrants and women who are ‘socially excluded’ in some way) but we also saw spontaneous memory sharing throughout the week. In addition to this week-long exhibition, we also organised a series of big one-off screenings at Coventry Cathedral, that have showcased some of our key archival findings and our digitisation and restoration projects, from an evening of programmes about Coventry’s ska scene in May 2018, to the widely-attended Cathedral of Culture event in December 2018, which featured a digitised and restored screening of Celebration, the programme made about Duke Ellington’s performance at the Cathedral in 1966. At all these events, our key aim has been to gather data which tells us about the value of the television archive for those diverse groups engaging with it. We are therefore simultaneously exploring broadcasting history through our archival research, but also understanding how television constructs, consciously or otherwise, the history of the city; in Coventry, this is a history of manufacturing boom and bust in the twentieth centrury, postwar life, a history of social (in)justice and race relations in mid to late twentieth century Britain, a history of gender and familial relations, a history of various musical subcultures, from punk to ska, two tone and new wave, and so on, for as Asa Briggs tells us ‘to write the history of broadcasting in the twentieth century is in a sense to write the history of everything else’ (1991, 2).

However, ultimately, most television archives, and certainly those maintained by the broadcasting industry, are not for either television historians or the general public. Acceptance of this shifts both the subject of the question ‘What do we make of the television archive?’, and also shifts the meaning of the verb at its centre. If these archives are maintained for the industry itself, and the ‘we’ in question becomes contemporary programme makers, then what they make of the archive refers not to what they think or feel about the archive, but rather what they make from or out of it. This is what the large majority of broadcast archives are for: recycling programmes, clips, or even a single shot or line of dialogue to make fresh programming. Gorton and Garde Hansen’s interview with the archive producer Mhairi Brennan in their recent book speaks precisely of this hunt for ‘fresh archive’ (2019); whether for a news item, or all manner of documentary programming, or to authenticate a historical drama, contemporary television is frequently made of the television archive.

It is perhaps more unusual for the academic historian to make something out of the television archive (or an encounter with it) other than academic writing or presentations, but a number of strands of work on the Ghost Town project have attempted to do just this, albeit through the process of collaboration with programme and film makers, and dramaturgs. In closing, I want to outline three of the ways that our project has contributed to making something of or from the archive.

Firstly, I have been most fortunate to have been working with the historian and documentarist John Wyver on a major archive-based documentary for the BBC about the making of Coventry’s modernist cathedral, consecrated in 1962. Along with our jointly supervised PhD researcher, Kat Pearson, we have spent a good deal of the last year or so tracking down and watching a wide variety of archival film about the cathedral for the documentary tentatively titled Phoenix at Coventry, to be broadcast in 2021. This detective work, which has found me playing a small part in constructing a programme which is made of the archive for the first time, draws on not one single broadcast archive, but multiple, professional, institutional, and private archives, and has found me rooting through cupboards in basements and excitedly examining the contents of boxes hauled down from attics. Whilst John and his team will ultimately make the documentary (and I am excited to see what they make of the archive we have found), participating in this hunt, making connections that have led to exciting discoveries, seeking out the obscure as well as the obvious, has for me shifted Carolyn Steedman’s ‘archive fever’ (2001, 18) out of the archive and into the city, across the country. In making, or rather preparing to make, something of the archive, just as in the writing of scholarly histories of television, there has always seemed to be just one more source to check, one more box to root through. Here, though, the excitement is for the potential to construct a more complete story on film, rather than through academic writing, and to participate in a (new to me) form of audio-visual historiography. What this will ultimately mean, I hope, is that the viewers of Phoenix at Coventry will end up with a heightened understanding of the importance of the archive, as well as a new perspective on the building of this wonderful cathedral.

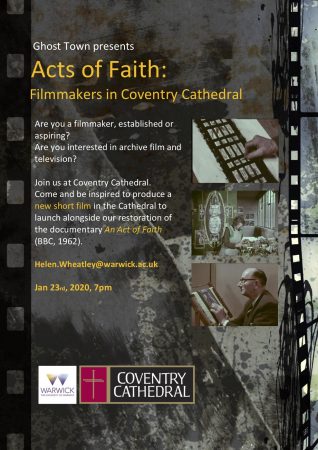

The second bit of making that the Ghost Town project has been involved with also relates to Coventry Cathedral, though this time a piece of archival television about the cathedral’s construction has been offered as inspiration for the production of some entirely new films. During the course of our hunt to find archival programming made in and about the city, we discovered that the Cathedral’s own archive held some complete, but badly degraded, copies of the 1962 documentary An Act of Faith on 16mm film. Having previously only seen fragments of this documentary, sent almost as an afterthought with other material we had requested for the project from the BBC’s archive, we knew that this was a significant piece of broadcasting history as the first BBC documentary to go into production in colour, made during the building of the new cathedral between 1956 and 1962 by the producer Robin Whitworth and the renowned arts documentarist John Read. The documentary had been produced in colour because the BBC thought it would be broadcasting in colour in time for the cathedral’s consecration in 1962; in the end, it was shown in black and white in the week of the consecration and then again in colour in the first full week of colour broadcasting on BBC in 1967. Commissioning a basic restoration job to be done on the cathedral’s copies of the film by our project partners the Media Archive for Central England, supported by a grant from the University of Warwick’s Connecting Cultures GRP, we have been able to once again see the film in its full form and with most of its beautiful colour restored. In advance of a public screening of this restored print, we showed the documentary to a group of local filmmakers, who have been challenged to creatively respond to Read and Whitworth’s pioneering presentation of the cathedral’s construction in their own work. Here, what is made of the television archive is not made out of it, but rather made in reaction to it. The archive programme takes on new life not by being remixed into something new but by providing creative inspiration, and filmmaking becomes a form of critical response to archive television. I greatly look forward to seeing what comes of this part of the project.

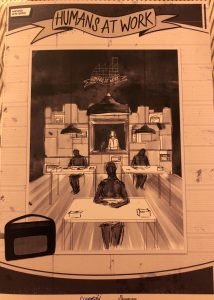

The final example of something being (partly) made of archive television relates to a new play which opened at Warwick Arts Centre this week: Humans at Work. This play was partly built from some workshops organised by the play’s producer Nobulali Dangazeli at Broad Street Community Centre in Foleshill, Coventry.

Here researchers from the Ghost Town project, along with the Photo Archive Miners and local historian Jitey Samra, shared archive television and photographs to initiate memory sharing amongst groups of older Coventrians who had worked in the city’s factories. Playing a series of clips of factory life which were made available to us by our project partners the Media Archive for Central England, we were able to provoke and chair a series of discussions and reminiscences about what was depicted on screen – and also what wasn’t. Often in these workshops, discussion of life on the factory floor, or participation in the endless industrial disputes that took place in the city in the 1970s and 80s, both depicted in the local news archive we brought along to the workshops, segued into talk about life around the edges of factory work: the factory sports leagues, the dances, the lunchtime stalls that women working in the factories used to run to sell whatever they had grown or made that week. In a sense, these conversations, these reminiscences, are what our workshop participants made of the television archive. Following these workshops, the writer Stephanie Ridings continued to conduct further research into Coventry’s factory life and subsequently wrote a play about three women working in a (fictitious) radio factory in Coventry, a play about community, solidarity and friendship, the genesis of which began precisely in our workshop participants identification of the stories that were not contained within the television archive. Watching this play, hearing the echoes of these discussions, was deeply moving, not only because it told a story of sisterhood, of women’s strength and of ordinary people’s defiance of racism in the city, but also because I could hear in it resonances from the TV archive and the engagements that accessing it for our community had inspired. This seemed proof, if further proof were needed, of the potential value of the television archive: for the Humans at Work project, archive television lit the fuse which led to memory sharing, in the first instance, and the creation of something new and wonderful in the second.

Helen Wheatley is Director of the Centre for Television Histories at the University of Warwick and principal investigator on the project Ghost Town: Civic Television and the Haunting of Coventry. She has published widely on issues of television history and historiography, including the edited collections Re-viewing Television History: Critical Issues in Television Historiography (IB Tauris, 2007) and Television for Women: New Directions (Routledge, 2016, with Rachel Moseley and Helen Wood). Her most recent monograph Spectacular Television: Exploring Televisual Pleasure (I.B. Tauris, 2016) won the BAFTSS Award for Monograph of the Year in 2017.

References

Asa Briggs (1991) The Collected Essays of Asa Briggs: Volume 3 (Harvester)

John Corner (2003) ‘Finding data, reading patterns, telling stories: issues in the historiography of television’, Media, Culture and Society, 25(2), 273–280.

Kristyn Gorton and Joanne Garde Hansen (2019) Remembering British Television: Audience, Archive and Industry (Bloomsbury)

Jason Jacobs (2006) ‘The Television Archive: Past, Present, Future’, Critical Studies in Television, 1:1, 13–20.

Stephen Lacey (2006) ‘Some Thoughts on Television History and Historiography: A British Perspective’ Critical Studies in Television, 1:1, 3–12.

Maire Messenger Davies (2007) ‘Salvaging television’s past: what guarantees survival? A discussion of the fates of two classic 1970s serials, The Secret Garden and Clayhanger‘ in Helen Wheatley (2007) Re-viewing Television History: Critical Issues in Television Historiography (I.B. Tauris), 40-52.

Rachel Moseley and Helen Wheatley (2008) ‘Is Archiving a Feminist Issue? Historical Research and the Past, Present and Future of Television Studies’, Cinema Journal, 47:3, 152-158.

Carolyn Steedman (2001) Dust (Manchester University Press)

Helen Wheatley (2007) Re-viewing Television History: Critical Issues in Television Historiography (I.B. Tauris)

John Wyver (2017) ‘Imagine a library…’ Illuminations blog, 22nd February, https://illuminationsmedia.co.uk/imagine/

What a brilliant piece Helen! Yes – making the programmes themselves accessible is vitally important. The elation I feel when I hear that a previously missing piece of television history has been recovered is occasionally followed by the thought that it may simply now be locked up in an archive where it’s now as unaccessible as it was when it was “lost”. It’s one of the reasons why I have so much time for Kaleidoscope who both screen rare material at their events and who have now also opened a reading room (cstonline.net//cstonline.net//www.tvbrain.info/shop/pdf-download-books).

‘The History of Forgotten Television Drama’ was a brilliant initiative – my wife and I thoroughly enjoyed attending the related events. The approach that you’re taking with ‘Ghost Town’ sounds very new and exciting and I wish you great success with it – particularly because you’re taking the subject matter and getting it out there to new, different audiences.

And so good – as always – to see John Wyver’s name pop up. First came across it in the amazing WTVA publication “PrimeTime” many years ago – itself established through a desire to access archival television history.

Really wonderful read. Many thanks! Much appreciated.

All the best

Andrew

Thanks for your response Andrew. I absolutely agree re: Kaleidoscope. They have been pivotal in helping us with access to some of the materials we have used, and did a brilliant job on the restoration of the Duke Ellington programme. They, like your own work, reach a wide range of people to whom TV history does really matter. I’m really glad you enjoyed the blog.

Helen

My pleasure Helen – it’s always great seeing archive television being made available (particularly when one thinks back to how tricky it was to view *anything* in the 1970s and 1980s) and to have it connecting with a new, different audience is even more exciting.

Also – sorry – belated thanks for the rather wonderful “The Story of Children’s Television”. That was a very lovely few hours of learning and memories! It must have given a whole heap of people a whole heap of happiness.

All the best

Andrew