‘You Win or You Die’, the seventh episode from the first season of Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011-present), contains a scene that has deservedly gathered attention and acclaim. One of the moments when the television series moves away from its source material, fans and critics alike have praised the introduction of Tywin Lannister’s character, who, played by Charles Dance, has a discussion with his son Jamie (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau) concerning House Lannister’s embroilment in the civil war that is unfolding in Westeros, whilst skinning a deer stag. Watch it here.

Quite refreshingly, discursive attention has not been negatively centred on issues of adaptation and fidelity,[1] but has instead paid recognition to the imaginative symbolism (the stag is the animal of the House Baratheon, a key rival for the Lannisters), the use of a real deer stag during production, as well as the fact that actor Charles Dance practised with a butcher prior to filming. Our attention lies with Dance’s acting and the way in which this gives texture to his characterisation of Tywin Lannister, in way that interestingly touch on issues concerning performance.

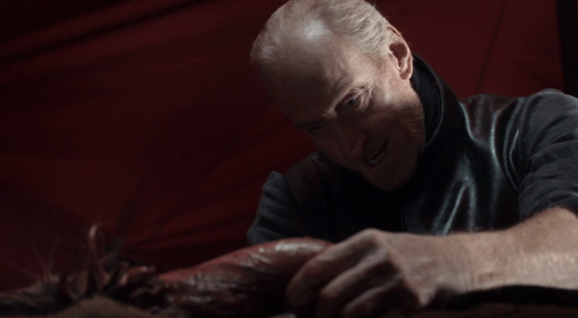

Just as well he is not a vegetarian: Charles Dance skins a deer.

Just as well he is not a vegetarian: Charles Dance skins a deer.

What is worth noting about this scene is that, first of all, it actually exhibits a lot of the skinning and butchering: unlike the familiar sight of a character playing the piano within a camera framing that just so happens to separate the character’s head/torso from the (talent double’s) piano-playing hands, the composition and cutting here emphasise, if not insist, that it is Charles Dance who is physically handling an animal carcass. Whilst the sequence is a composite of different takes (as the switch of the knife reveals), over the course of the four and a half minutes, we do see (and hear) Charles Dance cutting through flesh and sinew, pulling out guts, yanking back flaps of skin, and even placing one of the animal’s haunches over his shoulder. With short, sharp, powerful hand movements, nasal grunts, and visceral sound effects for the work of knife and hands, this sequence renders a visible (and audible) performance, of strength and skill, by character and actor.

That this scene was devised and included already sets up something about the intentions for the character: keeping up his physical skills, Tywin Lannister is introduced as a man who is always prepared, engaged in all aspects of warfare and who recognises the importance of physical actions and power (and their display). The quality of movement, enabled by the actor having received some training, is crucial, however, in terms of characterisation: the forceful, methodical, decisive and efficient economy of movement of the knife through different textures leaves no doubt that this character, whilst not revelling in violence for the sake of it, nevertheless is both willing and able to do what is necessary (for him, this is hinged around the protection and continued rise to power of the House Lannister). This encapsulates on the level of gesture and movement the text’s wider preoccupation with moral complexities; as Shannon Wells-Lassagne (2013, 417) observes, ‘the clear-cut villains that seem to people the novels soon prove to be more understandable villains, while the actions of the heroes are increasingly less morally palatable.’

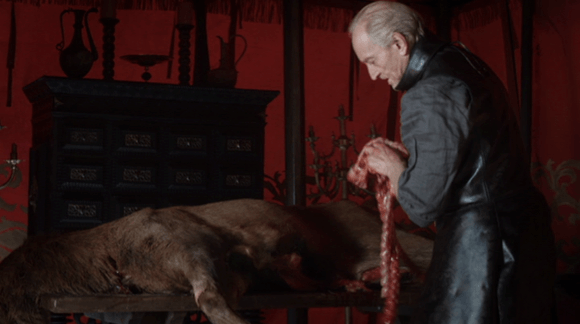

That will come out in the wash: a look of knowledge and composure.

Ironically, the dialogue of the scene at one point concerns itself with the use of ‘clean’ working methods for what is essentially the dirty business of warfare; and the theme of cleanliness and dirtiness is not only reflexively echoed in Charles Dance’s efficient handling of the knife, but also further developed in his repeated wiping of his hands. Necessary on a practical level for the handling of the knife, this cleansing of the hands of blood and visceral slime symbolically reflects the cost of doing what is necessary. This act, especially through its noticeable duration, implies that Tywin’s larger goal will entail repeated dirty acts, and – crucially for long-running and narratively complex television – will involve not only the climactic act of killing, but also its aftermath and repercussions. Fascinatingly, Dance looks at his hands before and while he is wiping them, instead of, for example, seeking more eye contact with his son. This suggests a sense of self-knowledge and steely composure for the character, who is aware of his actions and the costs they entail, and willing and able to face these – unlike Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth, he can deal with regicide-related stains, knowing that they will wash off. Having wiped his hands a second time, Dance’s Tywin grasps Jamie’s face with his left hand: this is not a rare gesture of paternal closeness for this character, but instead a tangible reminder that Jamie is, by deed and association, also tainted and marked (he is the ‘Kingslayer’ after all), and will have to get repeatedly and continually dirty too. (That it took Dance a couple of days to get the smell off his hands only underlines the physical marking, not dissimilar to war paint, of the son by the father here.)

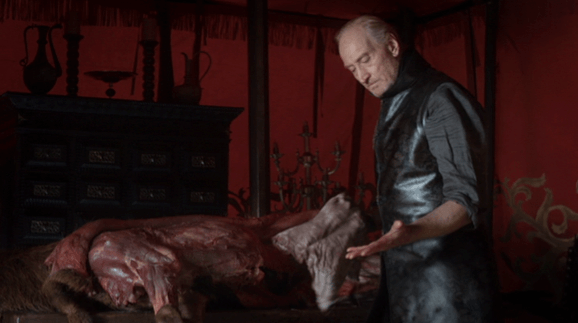

They both know where that hand has been: Tywin marks Jamie.

What runs further through this symbolically charged scene is a reflexive preoccupation with the notion of performance: Tywin and Jamie’s talk is flecked with references to reputation and image, and these are created and sustained through enactment. Indeed, Tywin in so many words tells Jamie and the viewer that the House of Lannister has its strength based on repeated, continual performance – it is because the Lannisters have a fearsome reputation, and know how to use this reputation, that they have power. This is both a strength (others act in accordance with the fearsome Lannisters’ goals) and a weakness (their power could begin to crumble with a slip in the performance). With House Lannister thus embodying the disciplinary power of performance (see Foucault 1977), the discussion of matters pertaining to performance is delivered during and through a performative act: the skinning of the deer. Possessing the most acute recognition of the power and fragility of performance, Tywin Lannister delivers an act of performance to his son (and any of the surrounding Lannister bannermen that may need to enter the tent) that can be understood as an animal sacrifice in a trajectory with the other performative rituals (such as weddings and coronations) that a ruling class such as the Lannisters must participate in in their quest for power and endurance. Framed evocatively by the deep red curtains of the tent, Tywin not only tells Jamie at the end of the scene that he needs him to ‘become the man you were always meant to be’, but during the course of the scene gives an embodied act of performance of this kind of masculinity to his son.

The kind of man a Lannister needs to be: a performance of masculinity.

Clearly, it is imperative that Tywin delivers a successful and convincing performance when skinning the deer, which in turn of course relies on Charles Dance doing the same. It is here worth reflecting for a moment on the fact that Dance has to manage what is a busy and physically involving performance under challenging circumstances. Receiving training from a butcher for an hour prior to filming is not much rehearsal time for the required confident handling of a knife and an animal carcass under visibly cold conditions that would affect grip and movement. (The fact that Dance does not do any cutting without taking his eyes off the carcass indicates the needed level of concentration and attention.) It would be a challenge to remain completely in character during this demanding, visceral, malodorous work and an understandable instinctive human response to, for example, flinch or wrinkle one’s nose at the smell of the guts as they come out. Charles Dance, however, does not slip, and this is crucial, for showing an instinctive human response here would be breaking character for his character, who performs being beyond such basic human concerns and frailties to himself and his son.

Unflinching: neither character nor actor slip in their performance.

Just as the character needs to perform a sense of strength, skill and physicality, so too does the actor here, to some extent. Whilst Charles Dance was a fan favourite for the part of Tywin Lannister – as Janet Moat notes in Screenonline, he is ‘often lazily cast as a villain’, such as the ruthless lawyer Tulkinghorn in Bleak House (BBC1, 2005) – he was also roughly a decade older than the character when cast, and did not exactly fit the description offered in the source novels:

Tywin Lannister, Lord of Casterly Rock and Warden of the West, was in his middle fifties, yet hard as a man of twenty. Even seated, he was tall, with long legs, broad shoulders, a flat stomach. His thin arms were corded with muscle. (Martin 2003, 611)

Charles Dance manages to establish this imposing, commanding presence in this scene through his mastery of the physically demanding performance under difficult conditions. (Such are the demands of handling the carcass that he gets audibly exerted roughly halfway through, but makes his shortness of breath work for him by using it to punctuate his steely vocal delivery when discussing the captivity of his other son, Tyrion, and its potential consequences.) Dance (who did not attend drama school, but took acting lessons) achieves this partly via the use of the Psychological Gesture, a Chekhovian acting technique which calls for the physical expression of the inner psychology of the character; their emotions, objectives and thinking corporeally condensed into a specific movement. With the knife and carcass here not passive, decorative props but the materials through which Dance creates his performance, he finds the core essence of the character through the physical act of skinning. In Game of Thrones: Inside the Episode, executive producer and writer D. B. Weiss has remarked that the repeated takes for this scene ‘didn’t seem to faze [Dance]’. We want to suggest that, on the contrary, bodily gestures such as here cutting and hacking ‘allow actors to identify specific emotions more clearly and to enter them in a quick and efficient way’ (Bloch 1993, 131), helping Dance in this scene to access, draw on and deliver the range of emotions (determination, anger, disapproval and frustration) demanded by the scene.

The Psychological Gesture is rarely used in finished performance, but here works beautifully to express the character ‘in condensed physical form’ (Chamberlain 2010, 72). It also subtly serves as a portent of the ‘butcher’s bill’ often referred to in the source material and gives credence to Tywin Lannisters sobriquet, ‘Butcher of Castamere’. Incorporating what is primarily a pedagogical device into the very fabric of his performance, Charles Dance in this scene tackles an eagerly anticipated entrance of a complex character in a high-profile television show, and utterly fails to disappoint.

Gary Cassidy is currently undertaking AHRC-funded doctoral research at the University of Reading. His thesis explores the rehearsal process of playwright Anthony Neilson, using filmed footage of rehearsals and interviews. He trained as an actor at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama and has thirteen years of acting experience – Equity name Cas Harkins – covering film, theatre, television and radio. Plans for future research focus on using his research methodology to explore the working processes of other contemporary theatre practitioners.

Simone Knox is Lecturer in Film and Television at the University of Reading. Her research interests include the transnationalisation of film and television (including audio-visual translation), aesthetics and medium specificity (including convergence culture), and representations of the body. She sits on the board of editors for Critical Studies in Television and her publications include essays in Film Criticism, Journal of Popular Film and Television and New Review of Film and Television Studies.

[1] See also Keith M. Johnston’s discussion in CSTOnline of how Game of Thrones ‘departs from, and rewrites, its core texts, often for reasons of budget, narrative coherence and performance.’

Thank you for this lovely post. Marking his son is something that never occurred to me. It is interesting to read reviews that have in depth analysis. I only wish that I could re blog this post to wordpress.