by Gary R. Edgerton

This strike is a strike for everyone in the industry.

—Fran Drescher, SAG-AFTRA president, 8 May 2023 (Jackson)

2023 is shaping up to be one of the more turbulent years in Hollywood’s storied history. The recent writers’ strike is less the cause than a symptom of larger structural and operational changes that began gradually at the dawn of TVIV (circa 2013), then suddenly upended Hollywood’s creative community in the post-pandemic present. This reckoning is also about more than entertainment; it mirrors an inflection point that is currently transforming the American economy writ large.

Entertainment is one of the most highly unionized industries in the United States. Six weeks of intense negotiations starting on March 20 between the WGA (Writers Guild of America) and AMPTP (the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers) ended with an official work stoppage at 12:01 a.m. PDT (Pacific Daylight Time) on May 2. This strike marks both a rupture in commercial relations and a breakdown in the tacit social contract that had existed between writers and producers ever since the last walkout in 2007-2008.

What changed in the intervening 15 years is the emergence of streaming. Amazon Prime Video initiated the subscription video on demand (SVOD) business on 7 September 2006. Netflix followed suit a little more than four months later on 16 January 2007. Fast forward to the 1 February 2013 when Netflix debuted House of Cards (2013-2018), thus innovating a decade-long rise of streamers as content creators and setting in motion an arm’s race in scripted and unscripted television programming and movies that has finally reached a saturation point.

FX Networks CEO, John Landgraf, first christened this development in the television sector as ‘Peak TV’ in 2014, arguing that the sheer volume of content would soon outrun the demand for it. Little did he or anyone else know at the time that the rapid proliferation of programming was just beginning. Peak TV morphed into Plus TV lasting for almost a decade where the future of television (and film) is now inextricably linked to streaming as a technological, industrial, aesthetic, cultural, and consumptive practice.

A significant dynamic that differentiates the strike in 2007-2008 from the one in 2023 is the evolving composition and ethos of AMPTP over the last 15 years. In 2007-2008, this approximately 400-member trade association was then headed by 11 Hollywood-centered television and film producers: CBS, Disney, Fox, Liberty Media/Starz, Lionsgate, MGM, NBCUniversal, Paramount, Sony, Warner Bros., and The Weinstein Company. Streaming had not yet disrupted the business model for TV and the movies in the US and globally.

Today, the eight most influential players in an increasingly slimmed down 350-member AMPTP embody the hybridized business philosophies and practices of both Hollywood and Silicon Valley: Amazon, Apple, Disney, NBCUniversal, Netflix, Paramount, Sony, and Warner Bros. Discovery. Not surprisingly, there are differences of opinion among AMPTP’s newly reconstituted ruling cartel, just as there are tensions amid the major entertainment labor unions who at the moment are demonstrating an impressive display of solidarity.

Fig. 1: (Left to right) SAG-AFTRA president, Fran Drescher on the picket line with WGA West president, Meredith Stiehm, outside Paramount Pictures

What is looming is the possibility of a tri-guild strike as early as July 1 since AMPTP’s respective contracts with SGA-AFTRA (the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists) and the DGA (Director Guild of America) are both scheduled to expire on June 30. Whether the strike expands to include other unions remains to be seen, as public bickering has already surfaced between the WGA and the DGA on what minor script modification if any are allowable for those TV programs and films that are still in production (Maddaus; Kilkenny).

A common tactic for both AMPTP and the WGA is to divide and conquer. For example, AMPTP effectively marginalized the WGA during the 2007-2008 strike when it shifted gears by negotiating directly and eventually agreeing to terms on residual payments with the DGA, thus forcing the WGA to pattern bargain and accept identical rates with AMPTP (Littleton 165-189). Likewise, the WGA and the other guilds employ backstage feelers to explore compromises with individual AMPTP members in order to reactivate stalled negotiations and end impasses.

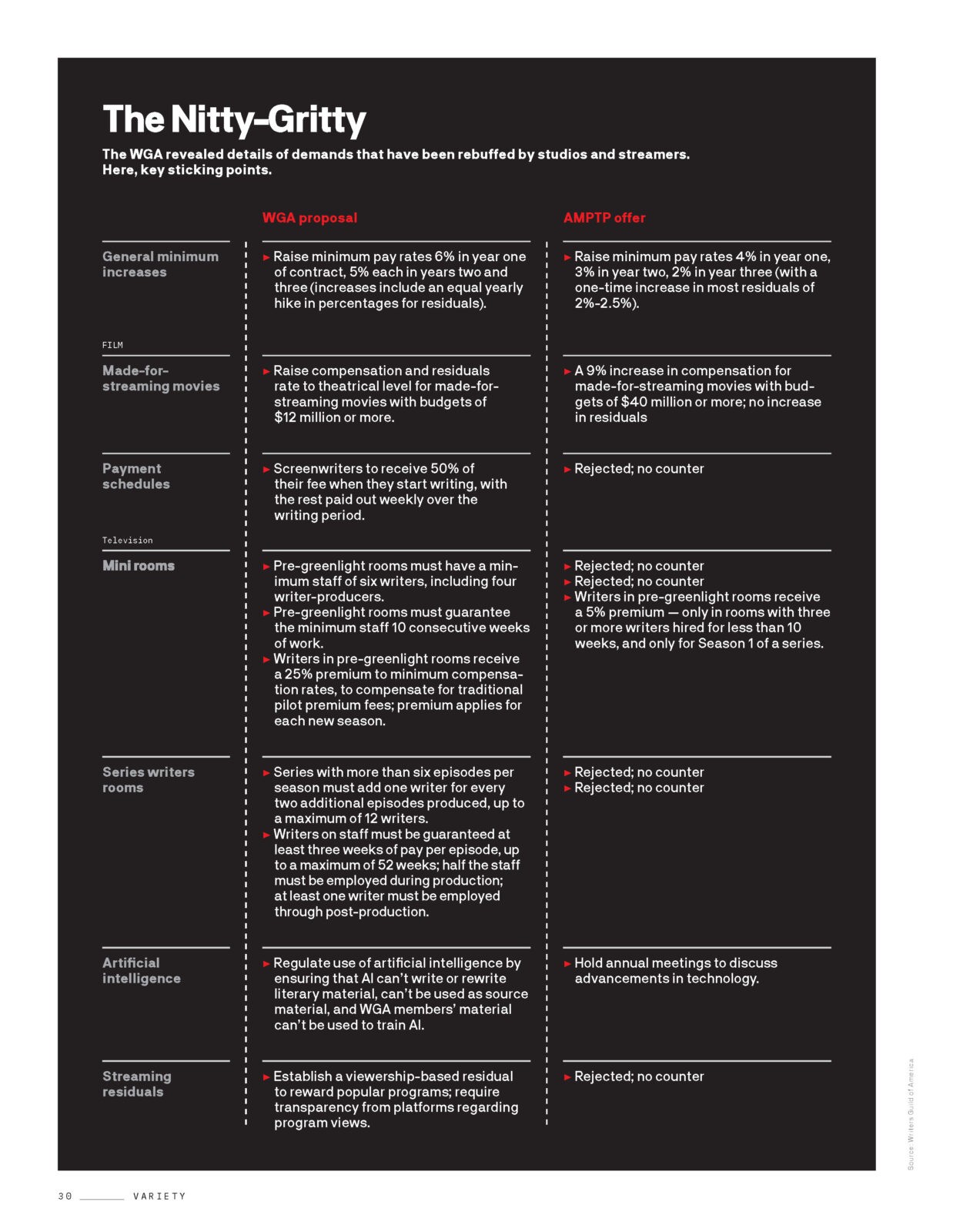

Suffice it to say that strike strategies and demands are highly complex and conditional on both sides. The most important issues for the WGA in 2023 cluster around three interrelated talking points: (1st) compensation (involving calls for higher minimum salaries for writers and raising streaming residuals to a comparable level with those for linear TV [broadcast & cable-and-satellite]); (2nd) working conditions (requiring mandatory staffing sizes that last over a guaranteed span of time approximating the pre-pandemic writers room model); and (3rd) limiting the use of artificial intelligence (AI) software in the scripting process. This precondition excludes AI from producing ‘literary material,’ which for the WGA means creating story ideas, outlines, treatments, and screenplays. A further stipulation bars the use of existing ‘literary material’ in training and thereupon improving future generations of AI scripting software.

The WGA moreover made its case on these three talking points in the court of public opinion through several tweets late on May 1 that thoroughly outlined its proposals side-by-side with AMPTP’s counteroffers, which were adapted and published in the following format in Variety’s May 3 issue (Littleton and Maddaus 30):

The bottom line is that the local, national, transnational, and global strata of the entertainment industry have all experienced seismic structural and operational shifts over the last decade because of the rapid growth and proliferation of streaming. Its impact has profoundly eroded the traditional business model for television and film without generating commensurate sources of profit. This sped up rate of change in the industry has left both the older studios and the newer media service providers scrambling to figure out how best to monetize streaming.

Hollywood in particular has entered a painful post-pandemic period of belt tightening in contrast to the halcyon days of peak production. For instance, the number of US scripted series rose from 182 in 2002 to 288 in 2012 to 559 in 2022 (Schneider 2023a). AMPTP members had already started slashing costs and downsizing production schedules en masse in the year preceding the WGA strike. Despite the heated rhetoric, no studios or streamers preferred a work stoppage. Once the WGA called a strike, however, it offered AMPTP an opportunity for wholesale housecleaning.

The entertainment industry’s transition to streaming has proven more costly than even the most conservative estimates. Similar to the strategy employed by the broadcast networks when they reallocated radio profits to fund the conversion to TV during the late 1940s and early 1950s, all of the major US-based streamers save the tech studios (Apple, Amazon, and Netflix) have relied on linear television earnings to offset the money needed for launching Hulu (29 October 2007), CBS All Access (28 October 2014; rebranded as Paramount Plus on 4 March 2021), Disney+ (12 November 2019), Peacock (15 April 2020), and HBO Max (27 May 2020; rebranded as Max on 23 May 2023).

Linear TV alone can no longer cover the capital investment needed to continue developing Disney, NBCUniversal, Paramount, and Warner Bros. Discovery’s respective streaming services. The ever-softening advertising market for the broadcast and cable-and-satellite sectors is fast reaching a tipping point because of the dramatic rise in cord cutting from 18% of all US TV households in 2014 to 52% in 2022. As a result, the majority of AMPTP’s ruling elite are turning to alternative ways to slash costs and save money.

This backstory offers some context as to why AMPTP has responded so uncompromisingly to the WGA’s proposals. Its rigid response is exacerbated by the widely reported outsized 2022 salaries paid to AMPTP’s highest profile tech entrepreneurs and media moguls, such Apple’s Tim Cook ($99.4 million), Netflix’s Ted Sarandos ($50.3M), and Warner Bros. Discovery’s David Zaslav ($39.3M). Disney’s Bob Iger’s income ($15M) may appear modest in comparison until one realizes it only covers two months wages following his reappointment as CEO for the ousted Bob Chapek ($24.2M) last November (Lang, Mass, and Spangler).

The WGA has therefore won the first battle of the strike’s public relations war by making its case for fairer compensation in contrast to the colossal earnings garnered by the industry’s top one percent. Nevertheless, the rule of thumb in labor relations is that strikers have their most leverage at the start of a walkout. WGA’s longer-term prospects depend on whether their approximately 11,500 active members will be joined on the picket lines by DGA’s 19,000 and SAG-AFTRA’s 160,000 constituents. A tri-guild strike would shut down all union-sanctioned AMPTP productions and likely nudge the producers towards making concessions.

Still, predicting how the strike plays out is merely speculative at this point. The DGA began negotiations with the producers’ alliance on May 10. This labor union has traditionally enjoyed the closest relationship with AMPTP of all the guilds and its talks could possibly facilitate an early compromise as was the case during the last WGA strike, which lasted 100 days from the 5 November 2007 until the 12 February 2008 costing everyone involved an aggregate of $2.1 billion.

SAG-AFTRA is scheduled to start its discussions with AMPTP on June 7. The actors are following the writers’ example by holding a pre-approval vote to strike before its negotiations with AMPTP to provide SAG-AFTRA’s leadership with the maximum leverage of having a landslide tally of support from its membership to set in motion if needed. As a point of reference, the results of the WGA member poll was 97.85% in favor of the eventual walkout.

On a macroeconomic level, this labor versus management drama now unfolding in Hollywood is much larger and more significant than being just an American story. The WGA strike is the canary in the coal mine for what’s happening in the combined television and movie businesses globally. The entertainment industry is in flux worldwide because of streaming. Hollywood no longer dominates the transnational screen trade as it once did throughout much of the 20th century, but the shrinking proportion of employee compensation, the diminishment of working conditions, and the ever-increasing presence and impact of AI software are threats to creative communities everywhere.

The erosion of fair market compensation and more equitable working conditions is directly connected to the integration of big tech into the global entertainment industry whereby principles and practices developed in the gig economy are presently being adapted wholesale into the routines and procedures of television and film. The notion of ‘gig’ actually originates in entertainment; it was part of the argot of jazz musicians beginning in the 1910s to describe a one-night or short-term engagement. It took a century before wildly successful gig providers such as Craigslist, Airbnb, and Uber, among many other high-profile startups, gave rise to the so-called gig economy, which is currently penetrating the very structure and operations of Hollywood and the entertainment industry worldwide.

Since the late 2010s in the US, hiring practices by AMPTP have separated many WGA members from the production process and rendered their positions more ad hoc than ever before. In television, for example, development or mini rooms have emerged as a popular alternative to pilot creation whereby a small group of writers (typically two to three and a showrunner) work on multiple scripts over a shorter durations of time (generally six to eight weeks). These newer protocols are replacing the traditional writers’ room (circa six to twelve writers and a showrunner) that lasted for a standard twenty weeks or more depending on the number of episodes for a particular program in a season.

Moreover, staff writers were routinely involved in preparation and shooting since television writing is an ongoing process. Today, writers are being hired more frequently as freelancers on an ‘as needed’ basis for shorter term gigs, thus limiting their participation in the overall production process. The effect of these recently adopted hiring policies is to disrupt the already tenuous career stability of writers who now need to cobble together multiple mini rooms per year to approximate what their annual incomes were just a few years ago. Relegating TV writers to gig status undercuts their long-established path for professional development and advancement.

DISRUPTING the TRADITIONAL CAREER LADDER

for EPISODIC TELEVISION WRITING

• Showrunner

• Executive Producer

• Co-Executive Producer

• Supervising Producer

• Co-Producer

• Executive Story Editor

• Story Editor

• Staff Writer

• Writers’ Assistant

The focus of the WGA’s third and final talking point is AI technologies that are already a part of virtually every aspect of television and film production. AI’s impact on scripting is now rudimentary at best as the WGA is more trying to get ahead of the curve on this discussion point with AMPTP. AI writing software today is used mainly to generate marketing and advertising copy and other related promotional materials. Nevertheless, AI raises the spectre of automation, which is another byproduct of the ever-expanding gig economy. Labor contracts such as the ones currently being negotiated in Hollywood are as much about erecting guardrails for the near future as finding solutions for present problems.

Fig. 3: The Hollywood Reporter (3 May 2023): The WGA’s Worst Fear

In the end, what is happening in Hollywood is indicative of the broader power struggle that is evolving in the gig economy both nationally and globally in 2023. It is no accident that Gallop reports that the support of Americans for labor unions has risen from 48% in 2009 to 71% in 2022. Besides SAG-AFTRA, representatives of unions directly involved in television and film production, such as IATSE (the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees) and the IBT (International Brotherhood of Teamsters), have joined the WGA on picket lines with non-creative media affiliates such as members from the hotel workers, teachers, and state employees’ unions.

The DGA is the one guild that has been noticeably lower key in demonstrating its support for the WGA strike. Part of the reason may lie in the DGA’s agreement to a total media blackout during its ongoing negotiations with AMPTP. Nonetheless, many of the DGA’s concerns—boosting wage floors and streaming residuals, protecting directors’ creative rights, codifying improved safety measures, supporting health and pension plans, and expanding diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives—do overlap with the WGA and SAG-AFTRA’s main proposals.

It is an old saw to claim that the creative media industry is an oxymoron, but the built in tension that exists between the art and commerce of television and film is indeed at another high-water mark. There are numerous reported examples of AMPTP affiliated executives issuing letters to contracted employees informing them that they must report to work and complete their production and post-production responsibilities (Schneider 2023b). Representatives from the producers’ trade organization have also floated short-term work opportunities to non-union international above-the-line talent to fill in during the walkout, thus risking accusations of strike breaking and union busting.

The fact of the matter is that the global entertainment industry is far more interconnected than ever before. International corporate stakeholders and talent have so far resisted AMPTP’s overtures for workaround arrangements outside the United States to avoid the bad optics and guaranteed blowback from other parts of the transnational television and film communities. Inside Hollywood, a long hot summer is definitely taking shape. All told, 2023 signals a fractious and unpredictable course correction in the structure and operations of the global entertainment industry resulting from the unintended consequences of streaming.

Gary R. Edgerton is Professor of Creative Media and Entertainment at Butler University. He has published twelve books and more than ninety essays on a variety of television, film and culture topics in a wide assortment of scholarly journals, anthologies, and encyclopedias. His latest monograph is Mad Men: TV Milestones Series (Wayne State University Press, 2023). He also coedits the Journal of Popular Film and Television.

References

Jackson A (2023) SAG-AFTRA President Fran Drescher Joins WGA Picket Line: ‘This Strike Is a Strike for Everybody in the Industry.’ Variety, 8 May. Available at: https://variety.com/2023/biz/news/fran-drescher-writers-strike-sag-aftra-picket-1235606636/.

Kilkenny K (2023) During a Writers Strike, What Constitutes ‘Writing’? The Hollywood Reporter, 17 May: 7-8.

Littleton C (2013) TV on Strike: Why Hollywood Went to War over the Internet. New York: Syracuse University Press.

Littleton C and Maddaus G (2023) A Broken Biz: Hollywood plunges into chaos as studios balk, writers walk and directors plot their turn at the bargaining table. Variety, 3 May: 24-31.

Lang B, Maas J, and Spangler T (2023) Big Paydays for Media’s Big Chiefs: CEO Compensation Stays High Even in Hard Times. Variety, 17 May. Available at: https://variety.com/lists/ceo-salaries-2022-bob-iger-tim-cook-david-zaslav/.

Maddaus G (2023) WGA and DGA Clash on Strike Rule That Bans Directors from Making Minor Script Changes. Variety, 18 May: 13-15.

Schneider M (2023a) Peak TV Tally: 599 Original Scripted Series Aired in 2022—A New Record, But FX Says We’ve Hit the Limit. Variety, 12 January. Available at: https://variety.com/2023/tv/news/peak-tv-tally-599-original-scripted-series-aired-2022-1235487593/.

Schneider M (2023b) Showrunners Stuck in the Middle. Variety, 18 May: 16.