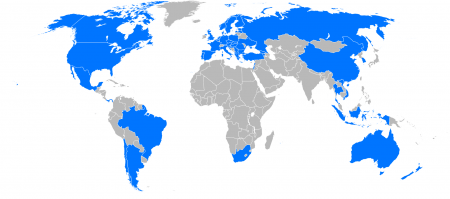

Ever since Strictly Come Dancing‘s inception in May 2004, settling into the fall season and the ‘build-up’ to the winter holiday period – at least in my own household – has become synonymous with watching Strictly‘s Saturday night entertainment, weekly on BBC1. The ballroom dance show format is a prime example of television as a globalisation tour de force, with local adaptations distributed (as Dancing with the Stars) by BBC Worldwide in more than 50 countries (see Fig. 1 below). The show’s producers have always spread a wide net – whilst keeping a clear local, national focus – to cast its ‘Strictly Stars’, convincing many a radio or TV broadcaster, journalist, soap actor, lifestyle guru, celebrity from the world of sports or entertainment, and even the odd (former) politician, to bust out some dancing moves. Who could forget Ann Widdecombe’s signature floor antics or Ed Balls’ very own version of Gangnam Style? Increasingly, however, both the casting of the original UK edition as well as its international counterparts are turning to the world of social media stars and YouTube influencers to draw in crowds – a trend that is certainly not limited to just the ‘teaching celebrities how to ballroom dance’ TV format.

I therefore wish to reflect further on novel aspects of television as a convergent and participatory media culture, as vloggers on the dancefloor lead me to contemplate online remix and collage. My discussion of the creative reuse of television by both viewers and content creators as platform users, its heavy re-circulation or ‘re-screening’ on different media platforms, and its ephemeral qualities, relates to larger debates on television as a part of multiple digital screen experiences (Evans et al 2017; Bennett and Strange 2011), with connected viewing (Holt and Sanson 2014), and new affordances of cross-platform entertainment (Green et al 2019) and participation (Jenkins and Carpentier 2013), especially regarding non-fiction crossmedia and transmedia storytelling in the attention economy (a.o. Hagedoorn 2015; Hagedoorn 2018).

Fig. 1: Map of international versions of Dancing with the Stars (February 2017). Source: Connormah, own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dancing_With_the_Stars_Map.svg

Established broadcasters are continuing to learn how to draw in viewership from very current viewing and screen cultures. Younger viewers, especially, seem to prefer other screens and content over ‘traditional’ television formats, lest creators are able to craft an experience that draws in and keeps their attention. Creators accomplish this feat by making a strong – and fresh! – connection with social/online media and cross-platform storytelling (the 2019 bi-annual conference of the Television Studies Section of ECREA therefore is focusing especially on studying the ‘youthification’ of TV and screen culture). In this context, Strictly‘s casting of a social media star like Joe Sugg ensures engagement of an already built-in, younger viewing audience – including ‘fans’ or ‘prosumers’ who are more than willing to help create a ‘buzz’ around the show on different social media platforms, where their fandom is already active. Rather than using ‘fan’ as a direct synonym for ‘viewer’, the concept here is found helpful to signal different and dynamic ‘modes of attention’ (Wilson 2016). Sugg counts 8,219,545 and 3,727,117 subscribers respectively on his main YouTube channels ThatcherJoe and ThatcherJoeVlogs at the time of writing. The casting, of course, also ensures media coverage on the star’s own online channels (see for instance Video 1 showing Sugg to be ‘switching up’ screens). Sugg also received positive reception from new audiences and gained new fans, including interestingly also more mature viewers (the main viewership for ‘traditional’ TV) who followed his Strictly appearances. Sugg has paid attention to this in his vlogging. Essentially, the inclusion of social media and cross-platform storytelling techniques in the ‘traditional’ TV-format of Strictly (and its weekly BBC2 spinoff Strictly: It Takes Two) ignites the ‘appointment television’ of Strictly with new urgency and meaning, whilst drawing in engagement of both larger and novel audiences around broadcast TV.

Video 1: Joe Sugg switching up screens: Strictly casting announcement in August 2018. Source: ThatcherJoe, uploaded August 14, 2018, https://youtube.com/watch?v=55ERjN0cODo

When the new Strictly season launched in September 2018, Joe Sugg and his partner Dianne Buswell’s opening performance – which even included a memefied homage to Fortnite – was watched online by more than 1,3 million people. This compared to an average of about 80,000 views for the other dances from the show’s same opening weekend, The Times (September 29, 2018) reported. This first performance (see Video 2) has raked in 2,460,601 views on YouTube at the time of writing. Betting on a social media star to ‘rake in’ views for the broadcast format is as mentioned not exclusive to UK’s Strictly alone – for instance US’s Dancing with the Stars (ABC) has over the years cast successful social media stars like Alexis Ren, Hayes Grier (who gained his notoriety on the (now defunct) video sharing service Vine), Bethany Mota and Lindsey Stirling – let alone exclusive to this particular TV format.

Video 2: Joe Sugg & Dianne Buswell jive to ‘Take On Me’ by A-Ha on BBC’s Strictly Come Dancing 2018. Source: BBC Strictly Come Dancing, uploaded September 22, 2018, https://youtube.com/watch?v=AMrSGMF4PZo

The increasingly closer connections described so far between the worlds of TV and social media have caused more traditional television formats to be included as a solid part of very current and ephemeral online forms of remixing. As a part of new viewing cultures or ‘screen cultures’, online ‘collage’ and ‘remix’ of television entails creative reuse by media users as active participants and storytellers. Such creative reuse is heavily re-circulated via online and social media platforms. This can be more bottom-up (fan-driven) as well as top-down (content creator-driven), or even a hybrid form. It also expands debates on television as a practice of both multi-platform storytelling and cultural memory (Hagedoorn 2015; Hagedoorn 2018) by exploring novel cross-platform dimensions of TV’s fleeting character.

Joe Sugg as an accomplished YouTuber (and Dianne Buswell is also more and more showing a deft hand at vlogging!) did not hesitate to film ‘behind-the-scenes’ of his Strictly training sessions, especially for vlogs reflecting on his training progress throughout the week and reviewing every week’s dance performance broadcast on BBC1 (see Video 3). The review is a common trope used by YouTube influencers and very popular with media audiences. Such creator-driven form of remix is Sugg’s own work, reviewing (together with Buswell) his own filmed training footage juxtaposed with BBC1 broadcast footage. The BBC separately filmed ‘behind-the-scenes’ training footage (for the main show Strictly Come Dancing as well as Strictly: It Takes Two) and sometimes featured highlights from Sugg’s vlog channel on Strictly: It Takes Two – as was the case for every contestant’s social media content as part of Strictly‘s own cross-platform storytelling techniques.

Video 3: Creator-driven remix: Joe Sugg & Dianne Buswell reacting to their Strictly Quickstep performance. Source: ThatcherJoeVlogs, uploaded November 23, 2018, https://youtube.com/watch?v=Mxy_CMbA_oc

Sugg’s substantial repertoire on YouTube (the content creator joined YouTube on November 13, 2011), and Instagram’s photo archive too, provides multiple opportunities for looking back. Fans enthusiastically take to and remix such audiovisual memories which are immediately available on YouTube and Instagram as dynamic ‘living’ archives. See for instance Video 4, a remix of Joe & Dianne’s Strictly dance performances and Joe Sugg’s own YouTube vlogs, scored to new music. Such ‘re-posting’ of self-created edits showcases considerable support, focused on sharing overall ‘good vibes’ (having fun, hilarity, challenges and pranks prevail, but also themes such as romance/cuteness, friendship and teamwork) – and can align with re-circulating favoured products too. Such support is further expressed through online comments and fanfiction of ‘Joanne’ (Joe & Dianne’s ‘shipping’ moniker). Making use of the ‘living archive’ of YouTube to re-examine Strictly‘s past also played a role in Sugg’s weekly dance training and preparation, as Sugg would often look back on previous dance performances – especially Harry Judd’s! – as study material for learning a particular new dance. Such ‘positive’ spaces of participation and reflection are of considerable importance in a culture where ‘drama scores’ – i.e. negative comments and discussions often draw in more attention – and especially on YouTube, which is a platform still considered to have one of the most negative comment sections on the internet.

https://youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=4whWq1btkTc

Video 4: Fan-driven (‘prosumer’) collage: a Joanne ‘shipping’ video remixing scenes from Strictly and Sugg’s own YouTube vlogs with new music. This video has been pinned on Joe Sugg’s Twitter page since December 2018 (at the time of writing). Source: Video Montage, uploaded December 3, 2018, https://youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=4whWq1btkTc

Television as a part of distinct digital screen experiences, also involves social media culture and platform algorithms pushing the existence of distinct ‘filter bubbles’ (Pariser 2011). User participation on any social media platform is (pre-)structured in interaction with the platform’s affordances and functionalities. As a result, users participate in sharing and (re-)viewing more of the same, based on prior likes, views, and follows. This could support an intensification of the user’s (positive or negative) filter bubble, as well as increased (self-)reflexivity. In the latter context, we are witnessing heightened opportunities for making cross-connections with television culture across multiple screens (I prefer ‘multiple screens’ over ‘second screens’, since for younger television viewers a so-called second screen is usually a first or preferred screen). Viewers increasingly recirculate television culture in online commentary, in self-created edits, and even in ‘shipping’ videos and memes as a type of visual commentary or reflection. Instagram especially is one of the key platforms where this collage culture is celebrated and encouraged. This heightened sensitivity to (self-)reflection via what I call ‘re-screening’ has become a key component of television as a viewing culture today. This is evident, for instance, in vlogs where Joe & Dianne’s look back on tour dance ‘fails’ filmed by fans in the audience, and in edits and memes created by fans remixing Strictly dance performances with sound from Joe Sugg’s vlogs (see Video 5). Remixing includes editing practices such as highlighting, freezing, slowing down, juxtaposing, commenting, often in relation to fan discussions online and engagement such as requests for particular creative content. Online fan culture is not without its trials and tribulations though, as fan accounts with monikers and avatars akin to or reminiscent of their idols increasingly are at risk of being deleted, as internet platforms are more and more driven towards facing liability for the shared content they host.

Video 5: A hybrid of creator-driven and fan-driven collage, showing Joe & Dianne’s reactions to unseen fails and memes. Source: ThatcherJoeVlogs, uploaded January 25, 2019, https://youtube.com/watch?v=ja9CWxZoJ0c

The short-lived nature of online culture – think of amongst others ‘Stories’ on Instagram, Facebook and Snapchat disappearing within a set amount of hours or days – brings considerable challenges, not just for fans, but also for researchers. Such texts and paratexts are reminiscent of times when television culture itself was more fleeting. This ephemerality of online remix and collage provides an opportunity to re-evaluate television as a practice of cultural memory. Especially in the context of new practices of traditional TV channels on platforms, apps and social networks, and specific challenges that come with ‘young’ TV use. Collage and remix activities also provide considerable access to highly ephemeral texts, for instance by the active recording and re-posting of fan-scraped ‘Stories’ – long-disappeared or deleted from their idol’s original platform – on platforms such as YouTube. Fans – and television studies researchers too! – revel in re-viewing and re-experiencing, whether it’s via collage, remix, visual commentary such as memes, or other appropriations of ‘traditional’ television. However, the impact of amendments to the EU’s Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market, which includes the infamous Article 13 making internet platforms directly liable for any copyright infringements their users commit, are yet to be foreseen. It may well stop these more novel and creative aspects of television’s online culture and reuse, in its tracks.

Berber Hagedoorn (b.hagedoorn@rug.nl) is Assistant Professor Media Studies at the University of Groningen. Her research interests revolve around audiovisual culture, creative reuse and storytelling across screens. She received the 2018 Europeana Research Grant award for digital humanities research into Europe’s cultural heritage. Hagedoorn is the Vice-Chair of ECREA’s Television Studies section (European Communication Research and Education Association) and organizes cooperation for European research and education into television’s history and its future as a multi-platform storytelling practice. She has extensive experience in Media and Culture Studies and Digital Humanities through large-scale European and Dutch best practice projects on digital heritage and cultural memory representation, including Europeana, VideoActive, EUscreen and CLARIAH. Hagedoorn has published on television in amongst others Continuum, VIEW, Media and Communication and see also https://berberhagedoorn.wordpress.com.

Bibliography

Bennett, James, and Niki Strange, eds. Television as Digital Media. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011.

Evans, Elizabeth, Tim Coughlan, and Vicky Coughlan. ‘Building Digital Estates: Multiscreening, Technology Management and Ephemeral Television.’ Critical Studies in Television: The International Journal of Television Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, 2017, pp. 191–205, doi:10.1177/1749602017698714.

Green, Stephanie, Amanda Howell and Rikke Schubart. ‘Introduction: ‘As if’: women in genres of the fantastic, cross-platform entertainments and transmedial engagements’, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, doi: 10.1080/10304312.2019.1569381.

Hagedoorn, Berber. ‘Collective Cultural Memory As a Tv Guide: ‘Living’ History and Nostalgia on the Digital Television Platform.’ Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, 2017, pp. 71–94., doi:10.1515/ausfm-2017-0004.

Hagedoorn, Berber. ‘Towards a Participatory Memory: Multi-Platform Storytelling in Historical Television Documentary.’ Continuum, vol. 29, no. 4, 2015, pp. 579–592., doi:10.1080/10304312.2015.1051804.

Holt, Jennifer, and Kevin Sanson, eds. Connected Viewing: Selling, Streaming, & Sharing Media in the Digital Era. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014.

Jenkins, Henry, and Nico Carpentier. ‘Theorizing Participatory Intensities: A Conversation About Participation and Politics.’ Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, vol. 19, no. 3, 2013, pp. 265–286, doi:10.1177/1354856513482090.

Pariser, Eli. The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You. New York: Penguin Press, 2011.

Wilson, Sherryl. ‘In the Living Room: Second Screens and Tv Audiences.’ Television & New Media, vol. 17, no. 2, 2016, pp. 174–191, doi:10.1177/1527476415593348.