On the 29th of October 2020, the BBC announced new plans to censor regulate the way that many of its employees use social media. The policy mainly applies to journalists but also extends to high-profile public figures such as Gary Lineker, former footballer and current presenter of Match of the Day. As the BBC explained in their press release, “We expect these individuals to avoid taking sides on party political issues or political controversies and to take care when addressing public policy matters”.

The timing of this new policy is interesting, coming amidst growing criticism regarding the government’s (mis)handling of, amongst other things, the free school meals initiative – a campaign largely spearheaded by the Manchester United footballer Marcus Rashford and endorsed by several high-profile BBC employees including Gary Lineker. The BBC’s new director General Tim Davie has suggested that this kind of endorsement is no longer appropriate as it does little to help “reduce accusations of political bias against the BBC at a time when it is under attack from the Conservative government and rightwing media outlets”. (Waterson, 2020).

To some extent, I understand the rationale for this new policy, particularly when applied to journalists – the BBC have a duty to remain impartial after all. However, the example of Lineker’s endorsement of Rashford’s important work raises questions over the distinction between the performance of public and private personas. Apparently the “views my own” disclaimer is no longer sufficient for high-profile individuals. But Lineker is not the BBC (he’s not even a journalist) – he is an employee of the BBC. He also works as a pundit for other broadcasters, some of whom have clearer political affiliations or agendas. How can Lineker reconcile these different brands within his own celebrity persona? I mean, he shouldn’t have to, should he? Morality clauses are nothing new, but this feels like we’re entering into more Orwellian territory.

There is also an irony (though it would be more accurate to call it a “depressing farce” but I’m trying to be impartial myself) [i] that this new policy wasn’t introduced during or immediately following the last general election, when BBC journalists such as Laura Kuenssberg reportedly breached impartiality rules and electoral commission guidelines [ii] (and may I remind you, these were journalists not sports presenters).

Of course, sports personalities such as Lineker and Rashford have a huge influence on public opinion (arguably more so than BBC journalists!) and in that sense they take on a greater responsibility around their public performance. However, it seems unfair and, more importantly, it seems unnecessary to police their work or personas outside of the BBC – “views my own” should be a sufficient preface to their opinions.

It is unnecessary because in “my view” the BBC are confusing impartiality with balance. According to their own editorial guidelines:

Due impartiality usually involves more than a simple matter of ‘balance’ between opposing viewpoints. We must be inclusive, considering the broad perspective and ensuring that the existence of a range of views is appropriately reflected. It does not require absolute neutrality on every issue or detachment from fundamental democratic principles, such as the right to vote, freedom of expression and the rule of law. We are committed to reflecting a wide range of subject matter and perspectives across our output as a whole and over an appropriate timeframe so that no significant strand of thought is under-represented or omitted. [iii]

Notwithstanding the fact that Lineker’s political endorsements occur in a space that is not managed or regulated by the BBC, it seems to me that their attempts to prevent him (and others) from articulating their own political and moral views is counterintuitive to the BBC’s aim of “reflecting a wide range of subject matters and perspectives”. What they’re doing, instead, is being excessively impartial (“in my view”) and therefore apolitical, whereas they could simply allow these high-profile personas (with the exception of journalists, perhaps) to continue sharing their thoughts and opinions on platforms such as Twitter, regardless of whether those views are liberal or conservative – and there are plenty of sports personalities to fill that latter camp.

I suspect that the BBC might eventually renege on this policy – not necessarily for journalists, but perhaps for others caught the limelight. In the meantime, however, I propose that we create a Twitter bot that periodically retweets the more political statements that figures such as Lineker have contributed to social media over the years. I just need to figure out how to do this.

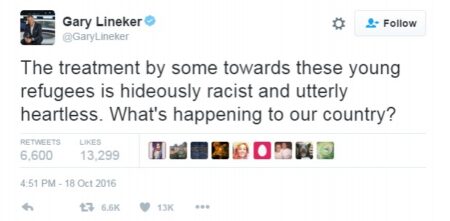

Fig. 3: Lineker’s response to David Davies’ suggestion that refugees entering the UK should undergo dental checks to verify their age. The Sun newspaper subsequently launched a campaign to have him sacked from Match of the Day.

JP Kelly is a lecturer in film and television at Royal Holloway, University of London. He is the author of Time, Technology and Narrative Form in Contemporary US Television Drama (Palgrave, 2017). He has published essays in various books and journals including Ephemeral Media (BFI, 2011), Time in Television Narrative (Mississippi University Press, 2012), Convergence, and Television & New Media. His current research explores a number of interrelated issues including narrative form in television, issues around digital memory and digital preservation, and the relationship between TV and “big data”.

Works cited:

Waterson, Jim (2020) ‘BBC journalists told not to ‘virtue signal’ in social media crackdown’ The Guardian. 29 Oct. Available at: https://theguardian.com/media/2020/oct/29/bbc-journalists-virtue-signalling-social-media-crackdown

Notes:

[i] You can read more about the depressing farce in my last post for CST: https:///bursting-the-filter-bubble-personalization-politics-and-public-service-media-by-jp-kelly/

[ii] https://independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/bbc-laura-kuenssberg-postal-votes-electoral-commission-a9242976.html

[iii] https://bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidelines/impartiality

Thanks for this JP. Very useful piece. Comes to something when opposition to children going hungry is seen as unacceptably political by the BBC