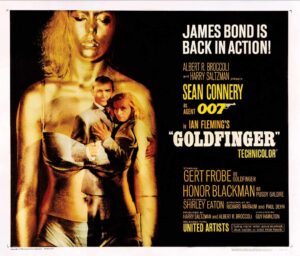

This year has seen the passing of two of the principal actors in The Avengers (ITV, 1961-69), Honor Blackman and Diana Rigg. Blackman is principally remembered for her role in Goldfinger, for which she left the program, but her time as Cathy Gale was a landmark in gender relations on British television, a moment when, she suggested, audiences were tired of roles for women “looking scared and handing out tea and sympathy” (Butler, 1963).

![]()

Rigg was touted for her stagecraft and latter renown in something apparently called Game of Thrones, but The Avengers was her passport to fame and she, too, stood for the new possibilities for women from the 1960s. Something truly different was brewing, at a time when casting women in an adventure series in the first place, and then not having them romantically involved with the male lead, shocked network executives.

Mrs Gale was conceived as a mixture of Grace Kelly, Margaret Mead, and Margaret Bourke-White. She aided Castro in Cuba, then worked for the British Museum. Her successor, Mrs Peel, was a scientist, journalist, and catsuit-wearing martial-arts expert.

Their colleague John Steed (Patrick Macnee), was a contradictory amalgam of Regency buck, foppish figure, and modish chic, arising from the cross-benches of tradition and modernity with carnation, bowler, and sword-stick at the ready; elegant, ironic, and phlegmatic. Steed and Mrs Gale, then Mrs Peel, were not quite lovers and not quite co-workers. A thrill was ever-present.

The Avengers was exported to over a hundred countries and inspired West End drama, South African radio, novelizations, comics, newspaper strips, annuals, music (“Kinky Boots”), a New Zealand/Aotearoa training film for women’s self-defence, and distinctive clothing lines. The program extended its target audiences from middle England to the US, and was revived a few years later, initially to advertise champagne and then as The New Avengers (ITV, 1976-77), a co-production with France. Twenty years later, it transmogrified into a regrettable Hollywood film (Jeremiah Chechik, 1998). Today, the series is troped in Karen Kilimnik’s ironised artworks, Muvizu cartoons, audio based on comics and fan fiction, and Batman ’66 Meets Steed and Mrs. Peel graphic novels.

Rigg’s character has stimulated the most paratexts. Consider Shark Inferno’s “Emma Peel,” the pitifully derivative “Don’t Look Back in Anger” by the always-awful Oasis, The Pretenders’ “Don’t Get Me Wrong,” “Emma Peel” by The Allies, Matmahah’s “Emma,” Mad Bomber Society’s “Emma Peel,” The Purple Avengers album Emma Peel Sessions, the ghoulish “(Remains of) Emma Peel” by Slot; and most famously, Dishwalla’s “Miss Emma Peel.”

In Chile, Emma Peel became a model for young women leftists opposing the fascist dictatorship. Colombian film critic Juan Carlos González rhapsodized her “mezcla de belleza glacial, misteriosa sofisticación, experticia en artes marciales e inteligencia perspicaz” [mixture of icy beauty, mysterious sophistication, expertise in martial arts, and acute intellect] while for Argentina’s La Nueva, she was simultaneously a marker of the past and a contemporary cult figure: “Sensual, atlética, valiente e inteligente” [sensual, athletic, brave, and smart]. Página 12 found her “la agente secreta más yeah yeah de todos los tiempos” [the most ‘yeah yeah’ secret agent of all time].

Just as the program’s flirty formality and pop-art pretensions account for much of its charm, the slight, affected ennui for daily life and distance from extreme emotions that coursed through it offered twinges of stereotypes and their counters that appealed internationally. At the same time, it incarnated the welcome decline of an empire and Britain’s stuttering attempts to become a post-industrial export economy.

When Blackman passed away, the BBC suggested her signature role was a “model for an emerging generation of women and an object of desire for their men.” The San Francisco Chronicle regarded Rigg as “the thinking man’s sex symbol,” and she appeared in one of Paul Feyerabend’s recurring dreams (Lakatos and Feyerabend 280). No wonder Rigg’s mom sent this letter to fans: “My daughter [who was in her late twenties] is much too old for you and what you need is a good run around the block” or that the actress warded off admirers by claiming it was illegal to sign autographs in the street.

The program did follow some dominant codes: both Mrs Gale and Mrs Peel were frequently trapped by sadistic men who wanted to harm them with psychological torture and powerlessness. The set-up troped conventional horror-film methods, such as the evocation of panic and point-of-view shooting from the assailant’s perspective. The idea of disfigurement as a gendered punishment, taking away woman’s principal currency in a patriarchal cultural economy, was referenced in mysterious adversaries cutting up their pictures. But the women prevailed, sometimes with assistance from Steed, in ways that showed their resourcefulness and rationality.

And then? On the cultural left, the 1970s began as a moment when the previous decade’s spirited rebellions of spectacle might find fulfilment. Instead, music became more corporate, fashion more flared, drugs more ruinous, sexual hypocrisy more blatant—and the UK’s underlying economic basis in cheap oil exposed and compromised.

It was a terrible time to be young and have imagined oneself as the next generation of change; instead, the shift was from Swinging London to decrepit decay. More genuinely disruptive social movements, such as feminism and black and gay power, suffered white-male intransigence and economic chaos.

1970s Britain was laden with a sense of endless rain, an unremitting damp that indexed a consistently dull yet fundamentally untrustworthy world. For those of us studying during a three-day week, with darkness folding in by 4 in the afternoon, reading and writing via gaslight, TV broadcasts ending early, shivering temperatures, misery abounding, Piccadilly thrown into darkness, collieries closed, politics a shamble, toilet paper scarce, and teeth cleaned without light, 1973 marked the fifth state of emergency declared in three years. The currency was soon devalued, and the International Monetary Fund invited to assist. Only admission to Europe saved the place.

And today? The country is a small-minded sham and a global joke, thanks to its departure from the EU and mismanagement of the pandemic. I’m glad The Avengers’ actors are not witnesses to it.

Toby Miller is Stuart Hall Professor of Cultural Studies, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana—Cuajimalpa, and Research Professor of the Graduate Division, University of California, Riverside. Toby can be contacted at tobym69@icloud.com and his adventures scrutinized at www.tobymiller.org.

References

Butler, Tom. “Gale Force!” TV Times, February 1, 1963, pp. 8-9.

González A., Juan Carlos. “El extraño caso de John Steed y Emma Peel: Los Vengadores, de Jeremiah Chechik.” Revista Kinetoscopio, vol. 9, no. 48, 1998, pp. 69-71.

Lakatos, Imre and Paul Feyerabend. For and Against Method: Including Lakatos’s Lectures on Scientific Method and the Lakatos-Feyerabend Correspondence, edited by Matteo Motterlini, U of Chicago P, 1999.