By Christa Lykke Christensen, member of research project Reaching Young Audiences

In September 2020, the Danish public service broadcaster, DR, announced their planning of minisjang – a new offering for the youngest children from 1-3 years old. It will be an online universe, not a TV channel, digitally available from April 2021 via DR’s general streaming platform, DR-TV, and via a separate app just like DR’s two other app streaming platforms for children’s content: Ramasjang for children 4-8 years old, and Ultra for children 9-14 years old [i].

Similar to the above-mentioned platforms, the new online minisjang, in principle, intends to present content within different genres, but matched to the target group of infants, taking into consideration their specific, cognitive, language and motoric development and level of experience. Music and songs, animals and their sounds will be an important part of programs. Since looking at other small children’s movements and actions is in itself attractive to infants, programs will show children playing with balls and other playthings, and it will all take place in a simple and recognizable universe. As the head of minisjang, Ramasjang and Ultra, Morten Skov Hansen, explained at the pitching event of ‘The day of children’s producers’ at DR these youngest kids will be confirmed in reality as it is and in what they already know by experience, such as, “if you show them a cow it must say muuh, not anything else” [ii]. First of all, content is planned to have a slow rhythm, to be based on repetition and recognisability and to be a safe universe for the youngest kids.

But why is the Danish broadcasting company only taking this step now? Denmark has a long and strong public service tradition going back to the early days of television. Ever since the 1950s DR have continuously and on a daily basis produced television programs for children and young people (Christensen 2013). However, they have never offered specific TV programs for the youngest children under four years of age even though other broadcast institutions in the Nordic countries with whom DR compare themselves, and are inspired by, already produce content for these young children, for example Bolibompa baby at the Swedish broadcaster, SVT. According to the director-general of DR, Maria Rørbye Rønn [iii], the argument for now developing the new minisjang is the threatening competition from economically powerful players, such as Youtube, Netflix and Disney+.

DR announced their new initiative in the same week that Disney+ launched their streaming service in Denmark. This event was not a random coincidence, but carefully planned, as Maria Rørbye Rønn explained at the press conference of the launch of minisjang. The powerful tech giants challenge and put pressure on all Danish media content for children, she said, and a small media house like DR are challenged to produce alternatives to that, since DR are in no way able to produce on the same scale as the big players. From the perspective of DR, the alternatives seem to be the importance of offering a Danish content to a Danish audience: “We produce content for children in Denmark. We use as a starting point their reality, their world, and that content does not have to be adapted for it to go in Italy, in China or in Chile. It is produced in Denmark, in Danish, and it has a completely uncompromising Danish distinctive character”, the director-general put forward as an argument for all children’s content in DR [iv].

With the launch of minisjang and with their other children’s content platforms DR understand themselves as asserting their place in a competitive market for content for children. This is motivated by at least two factors: changes in children’s as well as parent’s usage of media and the importance of being a small nation with national channels on which to show Danish children’s content produced by them.

Changing patterns of media usage

Digital media has entered the media landscape for everyone, and has become an important element of the everyday life of even small children. A study, based on interviews with parents of infants, and conducted by the media research section at DR concludes that about every third Danish child under the age of three streams content from DR on a weekly basis. It also concludes that about half of the age group use YouTube, and parents report that additionally their children watch content on other platforms, e.g. Netflix and ViaPlay. The youngest children typically stream popular content from DR’s Ramasjang on Youtube, or watch content at the DR TV channel, Ramasjang. This means that DR are challenged on three levels: infants watching content on YouTube or Netflix, which is not produced by DR, showing their content on a third party platform such as YouTube, and the fact that infants probably watch content targeted at an older age group.

However, infants do not find content on Ramasjang, Netflix or Youtube without help. They grow up with lots of opportunities to engage with all kinds of media, and several studies show how the influence of close family members plays a pivotal role in this engagement (Livingstone 2003; Siibak and Nevsky, 2020). Primarily, parents and siblings help infants to find the content that they think is relevant or interesting. Because of their use of mobile phones and tablets they are accustomed to finding content everywhere and will not automatically, as their absolutely first choice, find content from the national public service provider.

A digital generation becoming parents

These years we face a generation that grew up with digital media and are now in the process of having children themselves. This new parent generation is accustomed to making use of all media platforms and it seems natural to them to present media content to their children from a variety of digital sources. Hence, there is a stronger competition than ever, for a small nation content provider, to catch the attention of children from their earliest years. Being a small nation intending to produce content of quality for children, you need, and this is a key policy argument by DR, to produce alternatives to media content from the big players, for example by emphasizing characteristics of Danish culture, language and values. However, it also needs to be visible on third party media platforms since the family use those platforms.

These conditions are, of course, a big challenge for the Danish broadcaster. They have to meet this challenge if they are to avoid losing children as their media users; It applies to the children today and in future when they grow up to be (DR hope) loyal users of DR’s other media platforms. It is against this background that we can understand the initiative of launching the new minisjang signaling that DR are aware of the infants and take them seriously as media users who are entitled to content for their age group.

A small media provider versus tech giants

Considering all children’s content, DR during the latter years has faced this challenge in different ways, one of which is their visibility on platforms such as YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. The strategy is “presence where children are present”. It is not, however, unproblematic to be present on the tech giants’ platforms. In August 2020 the DR Ramasjang app (for the 4-8 years old kids) suddenly was removed from Google Play Store. The reason was that Google assessed content on Ramasjang to be inappropriate for children under 13 years. Specifically, it was about the crime-mystery series, The Ramasjang Mystery, where a child in each episode helps the host finding the villain, who for instance has stolen the circus director’s hat or the honeypot of the teddy bear. In each episode, the child gets a small licorice pipe for being willing to help and to solve the mystery. Google found this licorice pipe inappropriate, as it could influence children to begin to smoke.

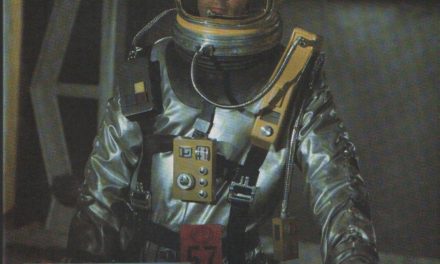

Fig. 2: The licorice pipes in The Ramasjang Mystery were judged inappropriate to children under 13 years of age.

A somewhat similar case took place a few weeks earlier when Google removed all Danish music from the Google-owned YouTube. The reason was disagreements in the negotiations for a new agreement on payment to Danish musicians. After much debate in newspapers and on social media, however, both the Ramasjang app and Danish music was back on Google. The interesting thing here is that Google is a big player, who want to use their power to dictate conditions that may influence content from small media players.

Regarding Danish children’s content, both in terms of factual and fictional genres, it is well-known for its intrepidity when dealing with difficult issues and feelings, such as divorce, death, bullying or feelings of sorrow or inferiority. Often, programs have a straightforward atmosphere – sometimes you can hear people swearing or farting, and children are taken seriously as independent individuals who are expected to have the courage of their convictions. Danish children’s content does not avoid difficult and hard topics that may provoke others. A recent example is the programme series on Ultra (for children 9-14 years old) ULTRA smider tøjet/ULTRA strips down. Five adults stand naked in front of a children’s audience, and the children may ask all kinds of questions to the five naked persons about their bodies. All types of bodies are represented in the panel, such as old, young, coloured, overweight, slim, pregnant or disabled bodies.

Fig. 3: Caption: ULTRA strips down. A series meant for easing children’s anxieties over body issues by exposing them to naked bodies.

According to one of the commissioners of DR Ultra, Christoffer Ebbesen, the idea behind ULTRA strips down was “to break away from perceptions of what is normal. As public service providers we must offer children a multifarious picture of bodies and help to give them another picture than the culture of perfection which they meet on social media and in Hollywood movies” [v]. ULTRA strips down did provoke a Danish right-wing politician from the Danish People’s Party, who found it depraving for children at that age to look at naked bodies. The program series also attracted attention abroad. New York Times [vi] and The Telegraph [vii] both wrote about the series with interest and understood that the programme takes up serious matters aiming to counter body shaming and encourage body positivity. Even if the media content for children produced by DR in general is seen as trustworthy among both children and parents, it is probably not the last time we will see tech giants interfere.

Christa Lykke Christensen is associate professor at the University of Copenhagen, Department of Communication where she is head of educations in Film and Media Studies.

References:

Christensen, Christa Lykke (2013). ‘Engaging, critical, entertaining: Transforming public service television for children in Denmark’, Interactions: Studies in Communication and Culture, Vol. 4(3), pp. 271-287. https://doi.org/10.1386/iscc.4.3.271_1.

Livingstone, Sonia (2003). Young people and new media: Childhood and the changing media environment, London: Sage.

Siibak, Andra and Nevsky, Elyna (2020). ‘Older siblings as mediators of infants’ and toddlers’ (digital) media use’, in Ola Erstad, Rosie Flewitt, Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, Iris Susana Pires Pereira (eds.): The Routledge Handbook of Digital Literacies in Early Childhood, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203730638-9.

Notes:

[i] minisjang was presented at a DR press conference, September 16, 2020.

[ii] Hansen, Morten Skov, August 18, 2020, at Børneproducenternes Dag/Pitching event for children’s productions, at DR’s Koncerthus, Copenhagen.

[iii] Maria Rørbye-Rønn, Director-General, at DR press conference, September 16, 2020.

[iv] Maria Rørbye-Rønn, Director-General, at DR press conference, September 16, 2020.

[v] Berlingske, February 13, 2020, https://berlingske.dk/kultur/organisation-gaar-i-rette-med-boerneprogram-fra-dr-i-er-i-gang-med-at-lave

[vi] The New York Times, September 18, 2020, https://nytimes.com/2020/09/18/world/europe/denmark-children-nudity-sex-education.html

[vii] The Telegraph, September 18, 2020, https://telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/09/18/adults-strip-danish-childrens-tv-show-challenge-perfect-body/