Conferences – and not the least thematic pre- and post-conferences – are great ways to bring together scholars with similar interests, discuss common challenges and build networks for potential future collaboration. This year’s ECREA conference, organised by Aarhus University, had the theme ‘Rethink Impact’ and gathered more than 1300 scholars in Denmark for four intense conference days last week. With three ongoing research projects focusing on different aspects of young people, entertainment and new platforms (Global Natives?, Reaching Young Audiences, Screen Encounters with Britain), we joined forces to organise a pre-conference related to our research agendas with the title ‘Young people, entertainment and cross-media storytelling: Perspectives and methods for investigating youth media’. The event was sponsored by the ECREA sections for Media Industries and Cultural Production and Television Studies.

As organisers, we were concerned about how many scholars might want to spend a day focusing on the often somewhat overlooked younger audience members. Luckily the response was overwhelming, leading to a (very!) full programme of 50 participants and 32 papers from scholars addressing various perspectives and findings from multiple national contexts. As Axelle Asmar’s presentation on recent Netflix teen series pointed to with the paper ‘Streams Like Teen Series’ (playing with the Nirvana album ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’), it does seem like there is currently more interest in understanding teen spirit and content among media researchers coming at the field from many different angles and perspectives.

Young people and influencer culture

The pre-conference opened with a keynote by Sophie H. Bishop who has worked extensively on content creation, social media platforms and influencer culture for many years (see, for instance, Bishop, 2018, 2019, 2021) and is a leading voice in the field. Her talk on young people and influencer culture presented her work as an advisor in the recent Influencer Culture Inquiry and the many challenges related to even defining ‘influencers’ and ‘influencer culture’ in the current media landscape. The talk introduced multiple topics and dilemmas that proved essential for the discussions following the rest of the day, including how to think of content creators across platforms and how children and young people are both creative workers and participating audiences in a complex web of interests and agendas.

Fig. 1: Sophie Bishop giving a keynote on Young people and influencer culture in the UK at the ECREA pre-conference.

From a media studies perspective, an interesting observation from the influencer investigation was the perceived division between people who have grown their brand and follower base on social media platforms organically and people who have appeared in reality TV programs and use their fame from here to build their name and brand as influencers. All production cultures have their own hierarchies and issues of recognition and distinction, and Bishop’s talk offered intriguing and transferable thoughts about authenticity, legitimacy, representation, and value from the influencer perspective. Bishop also recommended reading the platform session in the inquiry evidence for a fascinating encounter with how to evade answering concretely while seeming to give extensive answers.

The call for authenticity – and non-places

Following the keynote, the day had two parallel tracks of packed panels that pointed to how there are many bridges to build – conceptually and empirically – and recurring tensions when studying youth media and young audiences today. Several of these mirror general tensions in the media landscape, for instance, how legacy media are challenged by streaming and social media developments or the many questions around how to think of the local, global and transnational in the production as well as distribution and consumption of content. However, some notions kept popping up in many papers, such as a current focus on ‘authenticity’ when trying to appeal to young audiences across media.

Fig. 2: Three large-scale research projects co-organised the pre-conference on ‘Young people, entertainment and cross-media storytelling’.

For instance, Edda J. Arneberg and Evelyn Keryova both explored how to think of authenticity when teens value YouTube content in their everyday user practice, pointing to the various ways young people define ‘authentic content’. Similarly, Jakob Freudendal addressed how Danish filmmakers try to obtain authenticity and relevance through audience research, while Katrine Bouschinger Christensen explored working with co-creative methods to ensure authenticity in legacy media youth series through adopting strategies from DIY content creators. Ana Margarida Coelho and Ana Jorge presented a study of how Portuguese YouTubers target young audiences within the realm of beauty and fashion, contributing to the discussion of authenticity in portraying these influencers’ performed transitions into adulthood. Several papers examined how European public service media are rethinking their approaches for reaching young audiences by, e.g. moving into what Nadine Klopfenstein Frei and Fiona Fehlmann discussed as hybrid media content in Swiss Public Service Media or formulating new strategies for children’s content in the digital media system, as mentioned by Maria M.B. Skytte about the Danish Broadcasting Corporation.

However, while authenticity seems to be the industry buzzword (as also seen in recent industry reports by, e.g. the European Broadcasting Corporation), textual analysis of popular Netflix original drama series illustrates a trend of working with ‘non-places’ as a form of ‘grammar of transnationalism’ in these series, as discussed in a presentation by Christin Huchel and Carla Zech. Many popular Netflix series work with quite generic locations from the school life of young people and their everyday environment rather than portraying a more specific sense of place and perspective, but this can, of course, still be done with a focus on authentic feelings and dilemmas.

New developments call for new methods

Several presentations at the pre-conference analysed how young people are currently on a range of different platforms for many different reasons and asked how we keep up with and investigate this as researchers. For instance, Nicola Bozzi analysed what he argued to be the dissing of economy and crime lore influencers in relation to @Gangsta, Fabienne Silberstein-Bramford discussed fan fiction produced by young people, while Andong Li investigated how to understand mainland China young people rewatching Taiwanese idol dramas on social media. Other presentations addressed the role of platform performance, including Pilar Lacasa, who approached the term through the case of TikToker Charly D’Amelio.

Fig. 3: Close to 50 participants met on October 18 in Aarhus to discuss the role that entertainment media play in young people’s lives.

New platforms, media forms and media use call for developing new methods. This was the specific topic across several papers, e.g. when Amanda Skovsager Mouritsen outlined her approach to data donation in a study of TikTok use among adolescents and young adults. Romana Andò and Danielle Hipkins showed examples of ‘material thinking audience studies’ based on working with teen-produced video essays to try to gain a more nuanced understanding of their media use and preferences, and Ana F. Oliveira argued for working with digital narratives as a tool for teaching and researching Gen Z through arts-based research.

Pivotal shows and compelling complexities

Talking about remarkable tendencies and trends across the many papers at the end of the day, a recurring issue seemed to be that while many players currently fight to reach young audiences and explore new ways to be successful in this regard, there seems to be less focus on why it is a pressing issue to reach this audience and what can be regarded as characterizing quality content for them. It seems more important to reach them than to critically discuss the kind of content that one tries to reach them with. What can be regarded as ‘pivotal content’ or content that might change young people’s lives (as discussed by John Magnus R. Dahl in a presentation on RuPaul’s Drag Race as a pivotal show for queer youth)?

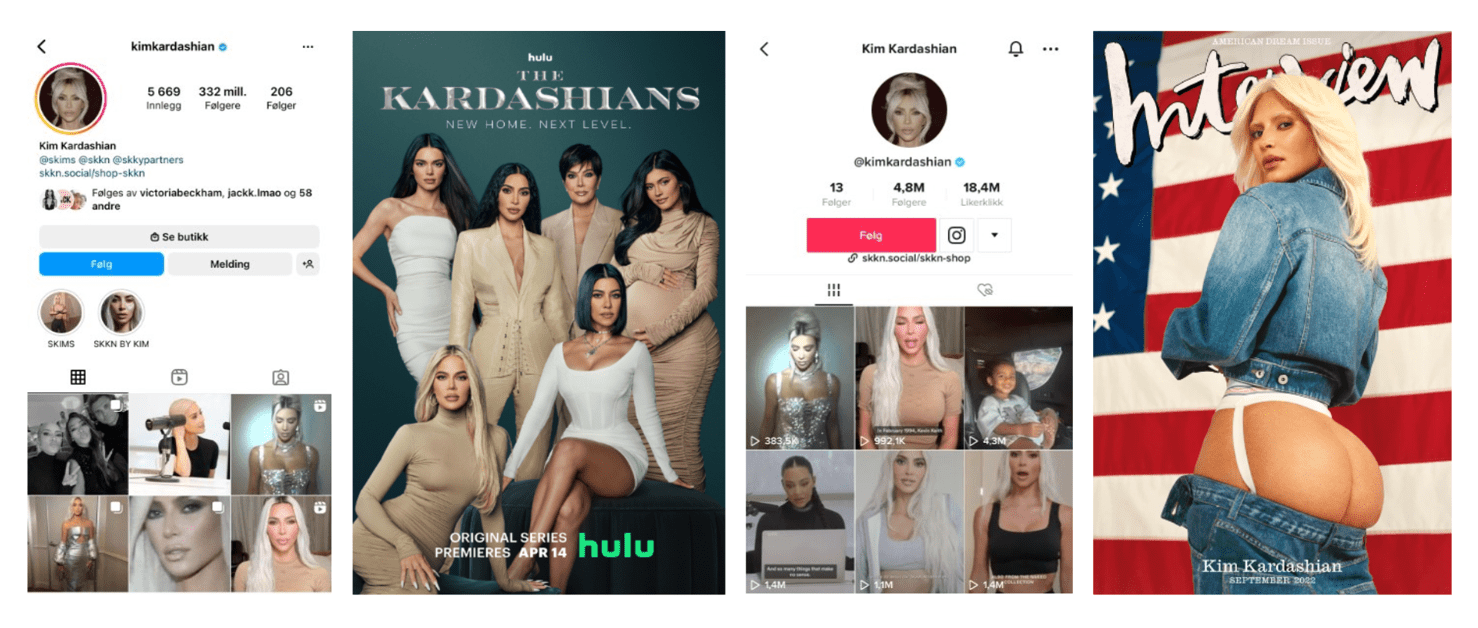

Fig. 4: Youth explores entertainment media across platforms and industries, requiring scholars to integrate different perspectives and methods when investigating their media use. Here illustrated by Kim Kardashian’s cross-media appearance on Instagram, television, TikTok and magazine covers.

Taken together, the pre-conference demonstrated the many compelling questions to raise and explore in the field of young people, entertainment, and new platforms – both among industry practitioners and researchers – and fewer clear-cut answers. Nevertheless, it seems conducive to compare case studies, methods and new ideas across borders and platforms. In our three research projects, we definitely got new food for thought when meeting a range of international colleagues with shared research interests, and we look forward to continuing many of the conversations started at the pre-conference in various formats and collaborations until the next possibility to meet IRL.

Eva Novrup Redvall is Associate Professor at the University of Copenhagen where she is head of the Section for Film Studies and Creative Media Industries and principal investigator of the Reaching Young Audiences research project (funded by Independent Research Fund Denmark, grant number 9037-00145B)

Vilde Schanke Sundet (PhD) is a Researcher at the University of Oslo. She has published extensively on television production, media industries, media policy and audiences/fans, and is currently working on the project Global Natives?, studying global platforms and youth entertainment media (funded by the Research Council of Norway, grant number 315917).

Jeanette Steemers is Professor of Culture, Media and Creative Industries at King’s College London and principal investigator of Screen Encounters with Britain: What do young Europeans make of Britain and its digital culture? , funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) (grant number AH/W000113/1).

References

Bishop, Sophie H. (2018) ‘Anxiety, panic and self-optimization: Inequalities and the YouTube algorithm’, Convergence 24:1; 69-84. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517736978

Bishop, Sophie H. (2019) ‘Managing visibility on YouTube through algorithmic gossip’, New media & Society 21:11-12; 2589-2606. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819854731

Bishop, Sophie H. (2021) ‘Name of the Game’, Real Life, June 14. Available: https://reallifemag.com/name-of-the-game/

Pre-conference website: https://hf.uio.no/imk/english/research/projects/global-natives/news/program-for-ecrea-pre-conferance.html