Rare is the Christmas break where I don’t have a pile of research to catch up on, so it was a pleasure to luxuriate in books for a change.

Two new arrivals were devoured instantly, and both reflected very different approaches to writing about screen media. One chiefly about film, the other squarely about television.

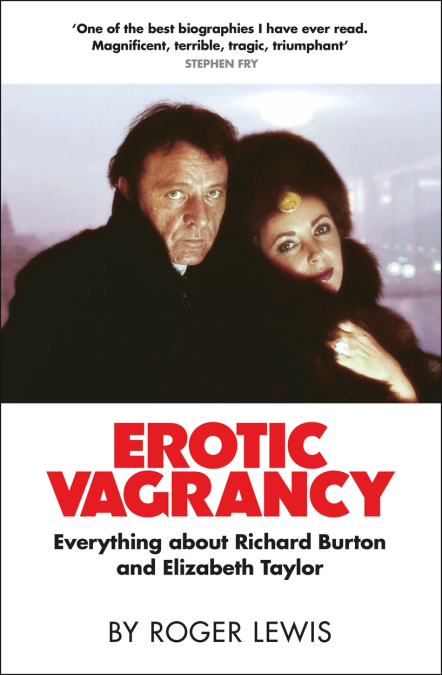

The first was Roger Lewis’s extraordinary Erotic Vagrancy (Riverrun, 2023), an enormous tome immersed in the lives and world of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. I hasten to add this is not a biography, Lewis having been burnt once too often by subjects that he ended up loathing (Peter Sellers, Anthony Burgess). His prologue demolishes the biographical art quite savagely, concluding it is an ultimately doomed effort to capture lightning in a bottle. Across 600 or so pages he makes the case for a more truthful approach, and his end result is tangibly the product of over a decade of struggle around this question.

A harsh reader might observe that Lewis sat at home, simply watching all of Dick and Liz’s films, making notes and then regurgitating them like some recap blogger. That would do him a deep disservice. Perhaps he is the exception that proves the rule, but Erotic Vagrancy is for my money a tour de force of improvisational free association. It reminds me of David Thomson and Ian Penman at times, in its rampaging across culture and the creative over-interpretation of the actors’ self in the art they make. In the process Burton and Taylor’s screen work becomes a back-door biography, proving that the scenic route is invariably more interesting.

The wild swearing from the author and the lives of excess of his subjects, cause gasps at a relentless rate. The middle chapter which attempts to timeline the making of Cleopatra (1963) is a perfect balance of precision and gossip, vulgarity and verve. My only real irritation was Lewis’s sideways sneer towards television, but in any case that’s a minor part of the Burton and Taylor story. As a screen historian, I would instinctively want to see more research, specific citations and an avoidance of assertion, but I found on this occasion that I simply didn’t care. The book was an absolute hoot.

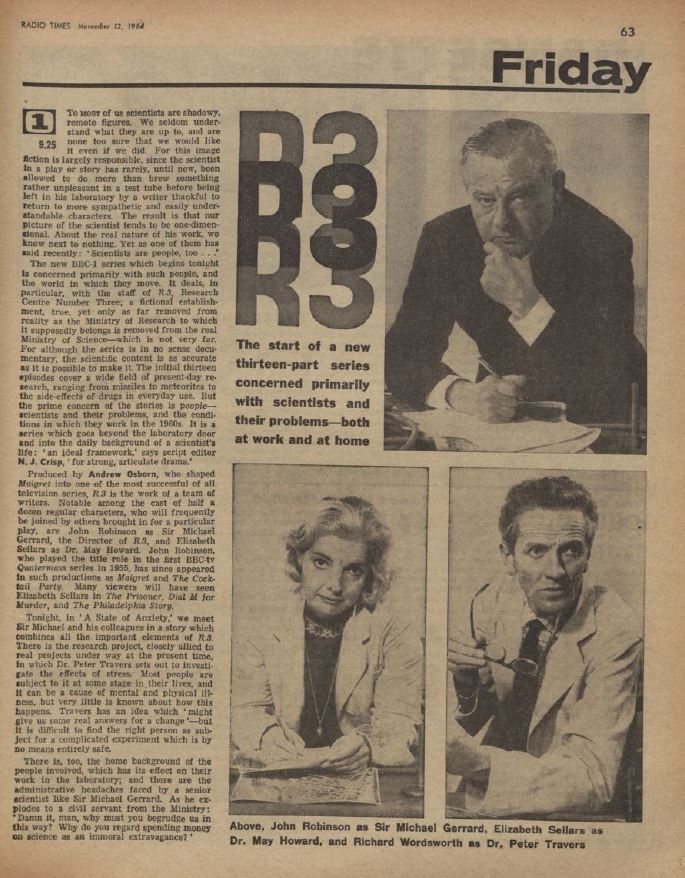

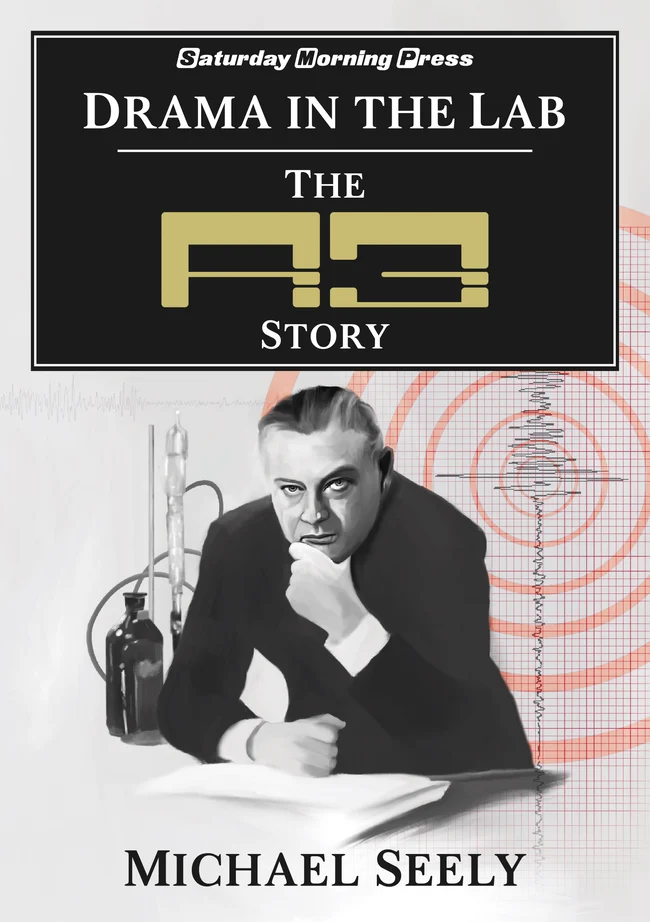

Michael Seely’s latest book, Drama in the Lab (Saturday Morning Press, 2023), meets head on one of the major challenges facing television historians – and embraces it over 300 very enjoyable pages. His subject is the genuinely obscure drama R.3 which ran for two series between 1964-65 on BBC One, and was about a ministry of scientific research – funded by the British Government – that was home to scientists with ambition, who would stop at nothing to pursue their theories. The drama centered on the personal and professional tensions of the science sector, something of a mysterious realm to the general viewer at that time.

Fig. 3: Snippet of the Radio Times, announcing R3 with the teasing advert of: “The start of a new thirteenpart series concerned primarily with scientists and their problems – both at work and at home.”

I first became aware of R.3 as an entry in Time Screen’s landmark “BBC Archives Telefantasy Listing” compiled by Andrew Pixley of this parish in May 1993 and published in the revised issue 7 that summer. Until now, I knew little more about the series than this list of titles and dates.

So why is this show so intriguing? Our understanding at that time and in the subsequent three decades was that it was a precursor to the experimental science drama Doomwatch (BBC One, 1970-72) about which Seely has published several good books. It was also said that after the recovery of Moonbase 3 (BBC One, 1973), R.3 was the only British-made telefantasy series – rather than play or serial – of which nothing survived. Not a single frame.

That has since proved not to be the case, but even today the archive holdings for R.3 are negligible. A more thorough combing of live telerecordings made by the BBC has revealed a trailer for episode 3 and part of the end credits of episode 10, but that is where the hunt for footage runs cold. Publicity photos and so-called ‘telesnap’ off-screen images are also very thin on the ground.

And here is Seely’s dilemma: his chosen programme is put out of reach in one vital sense, so how best to make an approximation of what it was actually like? That becomes the chief task of Drama in the Lab. Despite being regularly watched by around four million people, R.3 enjoys so little a collective folk memory that it may as well not have been shown at all. For posterity and understanding by later generations, then, Seely must start from scratch.

I sometimes think people make rather heavy weather of lost programmes. They should talk to radio historians who really know a thing or two about suffering. Or Medievalists, for that matter. For the television historian it ought to be a pretty good exercise – an opportunity – to reconstruct from paperwork, camera scripts, reviews. Anything available to you.

This is where Drama in the Lab succeeds so well. I sense the author hasn’t been spoiled with options, and was perhaps disappointed by the quantity of material available to him at the BBC Written Archives Centre. Just seven production files have survived, four of them covering individual episodes and only one for series two. He also draws upon a small number of artist files, and the occasional comment in the recorded minutes of internal meetings at the BBC (always a font of between-the-lines backbiting). With this material, he achieves a substantial and vivid account of the evolution of the original series concept from pilot through to its reinvention in year two. Seely demonstrates that an uncertain start and efforts to correct course resulted in a quite different – and much more interesting – series upon its return in 1965.

The core of the book, however, is an episode guide which isn’t just a list of numbers and names but a well-rounded and sensitively handled set of detailed plot descriptions based on camera scripts. These are some of the best I’ve read in this type of book, as they are clearly faithful to the page – capturing the humour, the character, and the intention of each script. At roughly 2000 words apiece they also have the capacity to handle the often complex debates around science, as well as convey a real sense of scene construction and internal pace. It is exemplary, evocative work, capped off by thoughtful assessments of each episode where Seely can loosen up a little and speculate on performance and directorial style.

The ambition of the series becomes all the more striking over the course of the book, with many episodes shot on film or using OB. The diversity of subject matter is impressive, too, taking on pollution and pesticides, the brain drain and nuclear survival. One episode about psychological torture goes much further than many of the spy series of its day; indeed, the test case experiment recalls (at least on the page) the harrowing extremes of David Leland’s Psy-Warriors made for BBC One’s Play for Today in 1981. That it was originally to be directed by the documentarian John Krish intrigued me even more. Another great ‘what if’ is the unmade story ‘Parasite’, which at various points could have been authored by Tom Clarke, Roger Smith and Troy Kennedy Martin.

Books devoted to individual series are to be treasured, and Seely’s label the Saturday Morning Press is helping to keep that tradition alive. Drama in the Lab is invaluable as it shows just how little we knew of R.3 back in 1993, and how far we have come. The influence on Doomwatch, particularly in R.3’s second series, is now very clear, although Professor Quist and his colleagues would surely have made every effort to shut the unit down. The other revelation is that R.3 isn’t telefantasy or science-fiction at all! Which just goes to show that myth is bunk. (Unless it’s about Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor.)

Erotic Vagrancy by Roger Lewis is priced £30.00 and available from Riverrun.

Drama in the Lab by Michael Seely is priced £11.99 and available from Saturday Morning Press.

What a smashing read! Many thanks Ian! Have to admit that I haven’t read a Roger Lewis book since the Peter Sellers volume… but I certainly hope to have a chance to enjoy the “R3” volume in the not too distant future.

So many enjoyable books out there at the moment. Currently enjoying some of the essays in “New Wave: 1980s TV in Britain” from Rodney Marshall. 🙂

Hope there’s more from you in the coming months! Much appreciated! 🙂

All the best

Andrew