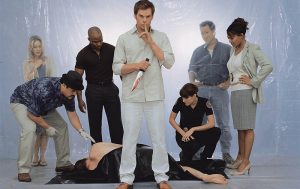

Internalising emotions, keeping secrets from friends and family, stalking men at night, and leading a double life. No, this is not Queer as Folk (2000-2005); this is Dexter (2006-2013) – a popular TV series that just reached its rather lackluster climax at its highly anticipated eighth season. Dexter, our favorite antihero, works for Miami Metro Police Deparment as a blood splatter analyst who, to everyone else, appears to be a rather ‘normal’ albeit awkward personality who goes about his everyday life as the resident ‘lab geek’. Closest to Dexter is his sister Debra, with whom he shares a rather intriguing, if complex sibling relationship. To the audience, however, Dexter is a vigilante serial killer, focused on enacting revenge on the trash of society who he is intent on eliminating for the benefit and indeed safety of its moral citizens. He is the moral guardian of the series and only the audience are granted access to the dark chambers of his deep subconscious through a series of candid voiceovers. Whilst a number of central characters weave in and out of stories, it is Dexter who is the central point of attachment, for reasons I had not anticipated prior to viewing.

Internalising emotions, keeping secrets from friends and family, stalking men at night, and leading a double life. No, this is not Queer as Folk (2000-2005); this is Dexter (2006-2013) – a popular TV series that just reached its rather lackluster climax at its highly anticipated eighth season. Dexter, our favorite antihero, works for Miami Metro Police Deparment as a blood splatter analyst who, to everyone else, appears to be a rather ‘normal’ albeit awkward personality who goes about his everyday life as the resident ‘lab geek’. Closest to Dexter is his sister Debra, with whom he shares a rather intriguing, if complex sibling relationship. To the audience, however, Dexter is a vigilante serial killer, focused on enacting revenge on the trash of society who he is intent on eliminating for the benefit and indeed safety of its moral citizens. He is the moral guardian of the series and only the audience are granted access to the dark chambers of his deep subconscious through a series of candid voiceovers. Whilst a number of central characters weave in and out of stories, it is Dexter who is the central point of attachment, for reasons I had not anticipated prior to viewing.

My initial attraction to the show was admittedly predicated on its incorporation of generic tropes from the horror and thriller genres: suspense, murders, frights and plenty of blood and gore. However, as the seasons unfolded and access to Dexter’s thoughts became increasingly palpable, I realised that my affinity with Dexter could be founded on the mirroring between his ‘secret life’ and my homosexual identity. Dexter, it seemed, could be understood as a gay figure – a material manifestation of ‘closeted’ sexuality that must remain repressed in order for him to sustain his heterosexual image and consequently, his acceptance into the society and profession in which he operates. As a gay viewer, I understood, even empathised with Dexter’s situation: his secrets, his performances of ‘normality’ and even his need to internalise his emotions in the safe haven of the unconscious where the viewer is granted privileged access. My reading of the text here borrows from Erving Goffman, as audiences are granted access to Dexter’s ‘backstage’ secret life, whereas the characters, for the most part, are limited to Dexter’s ‘on-stage’ performances. Dexter occupies a self-contained lab, separated from the wider space of the police department where he searches for his next victim to stalk and indeed kill.

Such performances however, were evidently transparent ‘on stage’ culminating in a number of characters identifying something ‘different’ about Dexter. Sergeant James Doakes is a particularly pertinent example here, for his discovery of Dexter’s ‘secret life’ resulted in one of the series’ most compelling showdowns. Only Dexter’s father Harry was to realise Dexter’s proclivity for killing, cultivating the production of a ‘code’ – a way of performing, which would allow Dexter to channel such urges whilst remaining in the shadows of society. It seemed to me that the ‘code’ represented an apt metaphor for the way gay men must monitor and regulate social behaviour in order to sustain ‘acceptable’ modes of presentation – as determined by the standards of heteronormativity. Audiences witness Dexter’s attempt to conform: he works out, plays sport with the guys from work, drinks beer, he even eats steak just about every day! Paralleling this, Dexter peruses the web to hunt for potential [male] victims, organizes a kill room, lures his victims and restrains them, flesh exposed – revealing his “dark passenger”. Although there is often a sense of sexual tension during the kill sequences, the possibility of Dexter’s homosexual realisation is often forestalled due to his inability to tap into his emotions, relegating such queer readings of the series to the murky terrain of subtextual accessibility.

A fictionalised fan-made video from Youtube featuring Dexter and Sergeant James Doakes

Subtextual accessibility will come as no surprise to queer scholars attuned to extracting the queer properties of ostensibly ‘normative’ televisual programmes. As a queer scholar, I feel as though my textual readings of such texts are frequently dismissed as ‘arbitrary’, ‘reading against the grain’ or worse, ‘reading too much into things’. How am I able to communicate the queer properties of a televisual text that speaks about my gay identity? How legitimate are these readings in a pool of more ‘acceptable’ or frequent readings? How do I conduct queer readings of texts whilst acknowledging the presence of alternative social and cultural identity markers that factor into the viewing experience? A concern which has occupied my thoughts recently relates the question of whether, in the twenty-first century when gay and lesbian characters are appearing with greater visibility, is it still productive for scholars to ‘read’ queer sexualities at the level of connotation? If, for so long, queer scholars have been advocating for gay and lesbian visibility in both film and television, I wonder whether there is still academic validity in ‘outing’ the queerness of any mass culture text? If so, we need to concern ourselves with the impact such readings have on the wider social, cultural and political functions of queer studies and the multiple if unstable identities it claims to represent.

Although I express ambivalence about the value and indeed purpose of such textual reading positions, I am ultimately preoccupied with such readings myself – both in terms of queerly deciphering Dexter and in my broader academic endeavors. Despite the fact that a number of queer scholars, including the late Alexander Doty, have warned against reducing mass culture readings to the “shadowy realm of connotation”, we must question whether these ‘shadows’ actually offer the viewer interpretive agency in projecting a queer self into the text where such readings can float freely (1993: xi). This is not to suggest that subtextual queer readings are practiced wholly without constraint, but to recognise the intelligibility of subtextual readings and the ability for the queer viewer to exercise their specific queer experiences at a deeper textual level. Even though a queer understanding of Dexter is only hinted at through the series, he is able to speak to me about my own former secrets, social performances and awkward situations that more openly ‘queer’ texts have largely failed to accommodate.

To contextualise the series in its entirety reveals that Dexter actually represents a less topical concern in discussions of sexuality – the label of asexual. Looking at the series more broadly could suggest that Dexter is to be better identified as asexual, defined in its abstract sense as a “lack of sexual attraction” (see Bogaert, 2012). Whilst such primitive definitions of asexuality are common, Dexter’s sexual awkwardness toward the opposite sex and, further, his initial reluctance (in season one to three) to engage sexually with Rita, brings into focus his lack of sexual drive and/or desire. The tension that arises here then, concerns the friction between the multiple reading positions that could be adopted in understanding Dexter’s complex sexual identity. However, labeling Dexter as asexual, even homosexual, runs the risk of essentialising his sexual identity against what has been instructed within the foundations of queer theory.

Although queer theory reminds us that sexual identities are constantly shifting, unable to be captured within a rigid homo/hetero binary, I find it particularly troubling in subscribing to way of thinking that forbids me from reading televisual texts from a position of ‘gayness’. A cursory glance at online reviews, forums and blogs circulating the series suggests that Dexter is to be best understood as being asexual, even bisexual from the textual clues offered. The problem I experience, is balancing these understandings – and indeed popular receptions – with how the text speaks to me about my own (homo)sexuality. Of course, every viewer will interpret and understand, if at all, Dexter’s sexual identity in a variety of ways. It just seems as if I am caught in a position between a deconstructionist view to sexuality as enforced by contemporary queer theory, and expressing my voice, as a gay reader, about my own subjective responses to Dexter. Aside from taking an autoethnographic approach to the series, I am ultimately limited to visual text(s) and the discursive material that circulates them with which to convey the deep connections and identifications I have with Dexter’s ‘secret life’.

Of course, contemporary televisual productions can regressively align Dexter’s aberrant sexuality with his monstrous urges to murder, as has been the case with many horror narratives such as the recent televisual production Bates Motel (2013-). Whilst such perspectives will probably continue, the agency remains for queer audiences to locate a sense of their own sexual identities– progressively moving forward from the eyes of monsters, to blood splatter experts such as Dexter Morgan. Although we are still accused of drawing blood from our victims, we are also starting to analyse it.

Adam C. Scales is a PhD candidate in the School of Art, Media and American Studies at the University of East Anglia. His thesis, provisionally titled ‘Logging into Horror’s Closet: Gay Fans, the Horror Film and Online Culture’ interrogates gay male fans of the horror film across several online micro-communities. His research interests include horror, fandom, gender and sexuality studies and the politics of taste.

Works cited:

[i] Bogaert, A, F. Understanding Asexuality. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012. Print.

[ii] Doty, A. Making Things Perfectly Queer: Interpreting Mass Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1993.

[iii] Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1959.