Partly due to an excess of clutter and partly due to the onset of old age, I’ve recently decided to tidy up my study. Over the years I’ve been an obsessive collector and haven’t been able to bring myself to throw stuff away. As well as shelves full of books and magazines, I have a substantial collection of film and television programmes on out-of-date formats, especially VHS tapes – some 300 of them, all carefully numbered and labelled with a note of their content. I haven’t got the facilities to play them, but I can’t bear to put them in the bin. And it seems I’m not alone – I’ve been interested to read recent e-mail exchanges between Visible Evidence members trying to contact archives to take their collections.

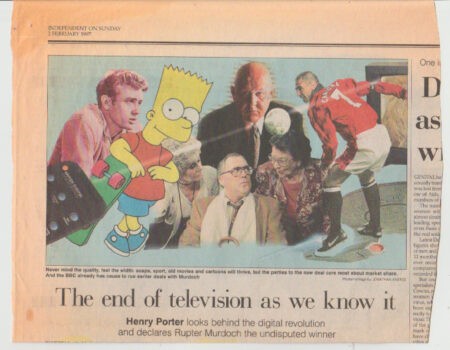

In addition to the video stuff, for many years I’ve been collecting press cuttings – some dating back to the 1980s and earlier. I have bulky envelopes full of them -some packed into boxes, others just piled up on shelves or on the floor -and there’s more in the loft. At one point I simply decided to throw away these old collections- after all they’re just a pile of waste paper taking up space. It would be easy just to dump them in the recycling bin (although that would mean quite a few trips as they would fill a lot of bins!). But I hesitated. I just couldn’t bring myself to ditch the past. These items are far more than the paper they’re printed on. They’re live objects, bursting with information and opinion – conjuring up decades long gone, but often with contemporary relevance. Looking through the plump envelopes with labels like ‘Murdoch’ ‘Satellite’ and ‘Media for Children’, I’m constantly reminded of the time before the revolutionary arrival of online and digital, when we relied on television and the press to keep us up to date with current affairs. And debates about the status of those media have been going on since the turn of the century. One of my cuttings from 2000 was already asking ‘is this the end of television as we know it?’

But this is my past as well as objective history. When I pull out from the pile a fat envelope labelled – for example – ‘Northern Ireland’, ‘Childhood’, or ‘Page 3’ – all topics I’ve written about in the past – I haven’t been able to resist looking through its contents and keeping the most significant. I can easily spend a morning reading through pages rescued from The Times, The Guardian, the Daily Mirror or The Sun from the 2020s or the 1980s. This is more than a pile of old papers – it’s fascinating stuff, telling us about the times when they were published as well as the topics they cover. I can’t bear to throw them all away, so I set myself a project – I will look through my cuttings and save the most significant (I might even write a blog about them!) and focus on the turn of the century.

One of the major themes dominating the pages from the early 21st century is a concern with the nature of the media themselves. This was a time of upheaval and innovation, with the arrival of digital formats. In 1997 the Independent on Sunday was already predicting that it was ‘The end of television as we know it’ (2 February). An allied topic was the accusation of ‘dumbing down’. I have a whole envelope given over to articles from the 1990s which deplored ‘the Disneyfication of British culture’ (Guardian 25 October 1999) and discussed the pressure on news-based programmes such as Panorama. On 25 October 1999 the Guardian’s media correspondent, Janine Gibson, reported on ‘fast food TV’. Quoting a study by Steven Barnett she wrote ‘Serious current affairs is being sacrificed for focus group-led stories while budget cuts are demoralising drama makers.’ And on 18 March 2000: Stephen Glover wrote in The Spectator that ‘democracy is being stifled by the dumbing down of current affairs television’…’it’s a sign of the times: less politics, more fun’. And ‘dumbing down’ continued to be a recurring theme. (The Times 15 February 2020).

The cuttings I have reflect, in particular, concerns about the BBC and Channel 4, as publicly owned channels. The status of the BBC became a major issue at the turn of the century, when questions were raised about the future of the licence fee (The Times 15 February 2020). In 2004 the Guardian ran the headline ‘BBC to be reined in’ (27 January 2004), while a few years later The Times reported that the ‘Tories plan leadership revolution at the BBC, and have pledged to ‘change management culture’ (3 February 2010). Concerns that public service broadcasting was under threat became a regular theme, usually linked to discussions of the wider implications of the ever-expanding new technology. The newspapers themselves were clearly affected as print was increasingly marginalised and online media increasingly attracted a growing number of users. At the same time broadcasters were making wider use of the new technology. In April 2003 the Guardian discussed the ‘Prime Time TV revolution’: ‘A growing number of rival satellite and digital channels means low budget entertainment involving members of the public will win the day’. But in November 2008 the paper pointed out that ‘cable, satellite and multi-channel launched 20 years ago’ – and debated whether this had been a good or bad thing. My cuttings include an increasing obsession with the new technologies and their possible effects on the established broadcasters. The themes of ‘on demand’ and ‘multi-channel television’ recur in accounts of the 21st century changes – described as they were happening. On 16 January 2008 the Metro wrote that ‘new research suggests’ that ‘TV schedules will disappear within 10 years, as …one in three now makes their own TV schedule’. Future provision will be ‘on demand’. Contributing to this change the BBC iPlayer was launched in July 2007.

Despite the changes to the structure of the media, debates around the future of the BBC and the principle of public service broadcasting have continued – as demonstrated by current attacks on the licence fee. However, in February 2020, The New European (20-26 Feb) published an ‘Agenda’ item on the BBC – illustrated with stills from Mrs Brown’s Boys and Strictly Come Dancing (two of my own favourite programmes). It was headed ‘You don’t have to love it, but you must defend it’, advice which, I would argue, should be widely followed.

As the years go by my collection of flimsy press cuttings is unlikely to be updated as newspapers are finally replaced by online media. Sitting in front of my computer screen I can only reflect on the special qualities that came along with turning their pages.

Pat Holland‘s most recent book is The New Television Handbook (Routledge, 2017).