‘In writing you’re always looking for conflict…’

Malcolm Hulke

‘To my mind the basic problem is that writers are by the nature back-room-minded introverts and yet, in the publicity jungle, they find themselves pitted against an army of highly extroverted actors and actresses. I don’t blame promotion people at all for taking the easy path of boosting the performers, if the writers fail to sell themselves as potentially equally good copy.’

Malcolm Hulke

Malcolm Hulke – generally known to friends and colleagues as Mac – was a successful writer for television, radio, the cinema and the theatre from the 1950s to the 1970s. My interest in him was sparked by coming across the pamphlet Here is Drama (1963) which Mac wrote for Unity Theatre in the collection of the Working Class Movement Library, something with which I have been associated for many years.

I already knew of Mac as a writer on Doctor Who and therefore undertook some research on him. This was published as a guest post on the Lipstick Socialist blog in February 2013. Subsequently, Five Leaves Press approached me in December 2014, wishing to publish the post as a pamphlet. I revised and expanded the article, and the result was published in January 2015. In June 2020 I published a greatly expanded version as a blog post: what follows is an abridgement of that post.

Born in 1924, Mac joined the Communist Party of Great Britain in June 1945, not, as he later wrote to a party official, because he was attracted to its Marxist philosophy, but because ’I had just met a lot of Russian POWs in Norway, because the Soviet Army had just then rolled back the Germans.’ He appears to have remained a member until the late 1960s, although his relationship with the party hierarchy had its ups and downs.

Mac began working as a writer with Eric Paice whom he had met at the left-wing Unity Theatre. Their first success was This Day in Fear (1958), an entry in BBC Television’s Television Playwright series starring Patrick McGoohan.

Mac and Eric went on to write four plays for ABC’s Sunday evening drama series Armchair Theatre (1956-1974): The Criminals (1958), The Big Client (1959), The Girl in the Market Square (1960), as well as The Great Gold Bullion Robbery (1960), an adaptation of a Gerald Sparrow play. For the same ITA franchise, they were commissioned by the legendary Canadian producer Sydney Newman to pen a series of science fiction adventure serials for children, starting with Target Luna (1960).

Mac was an active member of his trade union: The Television and Screen Writers’ Guild, formed on 13th May 1959. Ted Willis, a successful writer for stage, television and film (and former member of the Young Communist League) was elected chair of the new body.

In 1960, Mac co-edited the first three issues of the union’s new quarterly newsletter Guild News with another writer, Peter Yeldham. Later, in 1969, Mac also edited the Writers’ Guide, produced by the Guild for aspiring writers. When a second edition of this guide appeared in 1970, it included the following upbeat assessment: ‘The Guild is strong, it needs to be stronger. It is essential that anyone who works in films, television or radio joins immediately because individually we are nothing, collectively we can win for ourselves proper recompense commensurate with the inestimable contribution we make to our society.’

In the 1960s, Mac worked with Terrance Dicks on a number of episodes for ABC’s thriller series The Avengers (1961-1969). The series evolved over the decade from a gritty, black and white crime and mystery thriller into a stylish fantasy series, filmed in colour. In its later form, it combined English eccentricity with elements of ‘Swinging London’ in a manner carefully crafted to appeal to the American market.

Mac and Terrance’s episodes for The Avengers included The Mauritius Penny (1962) – in which a fascist organisation plan a coup under the guise of dealing in stamps – and Intercrime (1963) – which features a criminal organisation run as a commercial business.

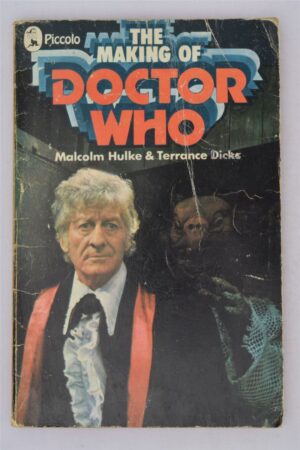

In 1968, Terrance became the script editor on the popular BBC1 science fiction serial Doctor Who (1963-1989). Mac had already been writing for the series, having co-authored the story The Faceless Ones (1967) with another writing partner, David Ellis, in which The Doctor remarks “Things are not always what they seem.” Working with Terrance, Mac wrote six serials for Doctor Who between 1968 and 1974, and also heavily revised a seventh without a credit.

Mac co-wrote The War Games (1969) with Terrance. In this, the time and space travelling Doctor and his companions Zoe and Jamie arrive in their vessel the TARDIS in the middle of what appears to be the First World War. The Doctor explains, ‘We’re back in history, Jamie. One of the most terrible times on the planet Earth.’ They then discover that other wars from history – such as the American Civil War and the Mexican Revolutionary War – are taking place in neighbouring ‘zones’. They are not in fact on Earth, but on a planet on which vast war games are being run by an alien race. The alien scheme is to assemble an invincible army to conquer the galaxy, a plan in which they are assisted by the War Chief, a renegade member of the Doctor’s own race – the Time Lords. The Doctor succeeds in uniting soldiers from different eras into a force which attacks and takes over the aliens’ headquarters.

In this story, Mac depicts war as violent and pointless, controlled by ruthless leaders who place no value on human life. He adds to this by not giving the aliens names, only titles such as ‘The Security Chief’ and ‘The War Lord’, and we never learn the name of their planet of origin.

Mac’s final script for Doctor Who, Invasion of the Dinosaurs (1974), dealt with the issue of environmental threats. At the end of this serial, the Doctor observes, ‘It’s not the oil and the filth and the poisonous chemicals that are the real causes of the pollution… It’s simply greed.

Katy Manning – who played the Doctor’s assistant Jo Grant in three of Mac’s scripts – told me: ‘…we all really trusted his writing for us and had great respect for his work.’

Among the other television series Mac wrote for were Gert and Daisy (1959), Tell It to the Marines (1959-1960), No Hiding Place (1959-1967), The Protectors (1964),GS5 (1964),Gideon’s Way (1964-1966),Danger Man (1960-1961, 1964-1968)and United! (1966-1967). He also worked as script editor on Crossroads (1964-1988), Spyder’s Web (1972) and the Australian series Woobinda (Animal Doctor) (1969-1970). With Eric Paice, Mac also co-scripted two cinema support films: Life in Danger (1959) and The Man in the Back Seat (1961).

A common theme in a good deal of Mac’s work was illusion and deception: the police in This Day in Fear are not the police; the stamp collectors in The Mauritius Penny are not harmless philatelists: the generals in The War Games are aliens. His message to the audience? Question what you think you see or what you are being told by the powerful. Ask yourself what is really going on. As the Doctor says in The Faceless Ones: ‘Things are not always what they seem.’

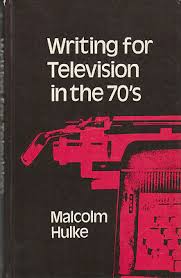

Mac drew on 25 years of writing experience for his book Writing for Television (1974) in which he explained the craft involved and also gave practical advice such as the need to get an agent. Naturally he encouraged young writers to join the trade union for writers: The Writers’ Guild of Great Britain. Andrew Cartmel, who was the script editor of Doctor Who between 1987 and 1989, says of this book:

I still remember Malcolm Hulke’s book— a glossy black hardcover with a red typewriter on the cover. It was packed with good advice (keep your submission letter — these days it would be a submission e-mail — very short and to the point) and also schooled me in the arcane script formatting that was de rigeur in those days… you kept a vertical slab of half the page blank, theoretically so that camera directions could be written in. It was a practical guide and also an inspiration. It was my bible. And thanks in no small measure to it, and to Hulke’s common sense guidance, it was only a few years before I found myself working as the script editor on Doctor Who – where I discovered that the same Malcolm Hulke had been one of the mainstays of the writing team during the golden age of the show.

I would suggest that in his non-fiction writings – Here is Drama, The Writers’ Guide, Writing for Television, and the children’s book The Making of Doctor Who (1972) co-authored with Terrance – he seeks to demystify, to hack through the technical jargon and accretions of tradition, and to help the reader understand what are admittedly complex topics. As he wrote in the first chapter of Writing for Television which he entitled What You Don’t Know You Don’t Know: ‘The more we learn about a complex subject, the more we realise there is to learn. And we can only start when we acknowledge there is something to learn.’

Malcolm died on 6 July 1979. Terrance Dicks recalls that, as a convinced atheist, he had left orders that there was to be no priest, no hymns or other ceremony at his funeral and that therefore his friends sat by the coffin not knowing what to do: ‘Finally Eric Paice stood up, slapped the coffin and said “well cheerio, Mac” and wandered out. We all followed him’.

Mac believed that writing was a craft, and should be respected (and paid properly) but that it was a craft that with imagination and hard work could be learned and that there was an onus on those who had been successful to help others onto the first rung of the ladder.

The final word must surely go to his good friend Terrance Dicks: he was ‘a very kind and generous man.’

Michael Herbert’s published work includes Never Counted Out! (a biography of Len Johnson, the black Manchester boxer and CPGB member) and ‘For the sake of the women who are to come after’: Manchester’s Radical Women 1914 to 1945. He blogs on radical history at Red Flag Walks and on science fiction at Fantasies of Possibility. His post on Malcolm Hulke can be found at: https://fantasiesofpossibility.wordpress.com/2020/06/25/doctor-who-and-the-communist-the-work-and-politics-of-malcolm-hulke-1924-1979/