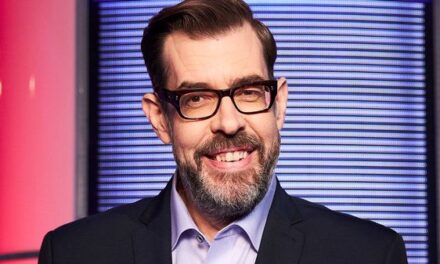

2024 has started with a bang for TV. Shows like The Traitors (BBC1) and Mr Bates vs The Post Office (ITV) have had around 10 million people tuning in to each episode, reminding us of the social relevance and transformative power of the medium. As television scholar, Amy Holdsworth, notes, TV acts as a ‘point of collective identification’ (2011:145), not just between the viewer and what they see on the screen, but between the audience as a group, sharing the experience of watching. We’ve laughed and cried together, and been outraged by the underhand tricks of the traitors and the Post office – we are a community made by TV. But for the small army of skilled freelance workers who make the programmes that build communities the last year has been a nightmare and this year looks like it might be even worse. The UK television industry is currently in crisis, caught in a perfect storm created by Covid-19, falling revenue from advertising, a crashing economy, pressure on the BBC licence fee, and the knock-on effect of the actors and writers strikes in America. To survive the storm, the industry has tightened its belt, cutting back on commissions and programme-making. This ‘organisational resilience’ – the ability to contract quickly and cheaply when needed – might see the broadcasters and bigger companies safely through to better times, but for the freelancers – and for us, the audience – the result of this slow-down could be catastrophic, throwing into sharp relief an industry that is characterised by a lack of care for its workers.

The UK television industry is a major player in the global marketplace with a £1.48bn global TV export but this figure relies on the labour of the thousands of skilled freelance workers who prop up the industry. Television production might seem like a glamorous job, but it is basically a gig economy with freelance workers moving from production to production, contract to contract, responsible for their own sick pay, maternity pay, and safety net when things go wrong. The boom or bust nature of the industry – an abundance of work one minute, none the next – means there is often the danger for freelancers of times being tough, but in the current climate they are at an unprecedented crisis level.

Financial problems affecting major broadcasters are hitting freelancers hard, with work disappearing as programmes are cancelled and commissions stalled as part of cost-cutting initiatives. In October last year, the BBC announced the cancellation of its weekday drama series, Doctors, which has been running for 23 years, blaming the super inflation in drama production costs and the restrictions of the frozen licence fee for this decision. Similarly, Channel 4 has announced that it will not renew the production contract for its live daytime magazine show, Steph’s Packed Lunch at the end of the year, citing ‘difficult decisions about which programmes to invest in to best drive our digital-first strategy’ as the reason for cancellation of the show. However, these cost-cutting exercises mean a devastating loss of ‘bread and butter’ work for freelancers on long-running shows that put food on the table and allow some stability in the form of longer or permanent contracts. Permanent staff at Channel 4 are also about to feel the pinch; in response to ‘the worst TV advertising downturn since 2008’ and the drive towards digital, the channel is planning to streamline by axing up to 200 jobs – their biggest round of redundancies in 15 years. The SAG-AFTRA and WGA industrial disputes in America have also played a part in the current crisis for freelancers. A survey of 4000 freelancers carried out by the industry union, Bectu, on the effects of the strikes on the UK’s film and TV industry found that three quarters of respondents were currently not working and 80% had their employment directly impacted by the disputes. 35% were struggling to pay household bills, rent or mortgages.

At its annual conference in May 2023, Bectu declared a state of emergency for freelance workers, noting that ‘this year has been unusually quiet for freelancers in the Unscripted genres, and many have not worked at all since January or earlier.’ The Film and TV Charity is also concerned about the situation, with its latest campaign claiming, ‘the strikes may be over but the emergency is not’. They state that ‘in the 100 years since the Film and TV Charity was set up to support people working behind the scenes, things have rarely, if ever, been this bad and we are struggling to keep up with the demand for our support.’ The charity reported an 800% increase in demand for their Stop Gap Grants over the summer, helping people to cover rent or mortgage payments, along with energy and food bills. The cancellation of Doctors (filmed in Birmingham) and Steph’s Packed Lunch (based in Leeds) highlights the fact that the future is even more uncertain for regional workers in a notoriously London-centric industry.

Fig. 1: Campaign banner “The Strikes May Be Over, The Emergency Is Not”. Source: Film+TV Charity.

The dire state of the industry is also causing a mental health crisis for freelancers. Industry reports such as Eyes Half Shut (Bectu 2017) and The Looking Glass (Wilkes, et al. 2019) have long warned of the toxic working conditions industry workers suffer, including dangerously long hours, lack of work-life balance, discrimination, and bullying. Because of the precarious nature of the work and the informal hiring practices rife in the industry, freelancers are often forced to put up with these conditions to secure their next job. The result is a shockingly high number of workers whose mental health has suffered as a result, with two thirds experiencing depression, compared to two in five nationally. In one survey, over half of the respondents had contemplated taking their own lives.

The current situation for freelance television crew is dire, and if things don’t change the future for television is bleak. Organisational resilience is all too often at the expense of the financial and mental health of the most precarious workers, with black, disabled, female and working-class freelancers struggling the most. The industry is gambling with the proposition that high quality, diverse, culturally enriching TV can be made on the back of an undervalued, casualised workforce. There is a moral argument about basic fairness and social justice here: the success of UKTV should be shared with its workers, not based on their exploitation and at the expense of their mental health. But there is also an immense cultural risk that is being taken that popular, culturally-rich and diverse TV can be made under these conditions.

Mhairi Brennan is a Research Associate at Aston University working on the AHRC-funded ReCARE TV project. She has previously worked in television production and as a lecturer in Television and Screen Industries. Her research interests include television production and archival practices, and her first monograph, Archiving the Referendum: BBC Scotland’s Television Archive and the 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum, will be published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2025.

Jack Newsinger is Associate Professor at the University of Nottingham, UK. He has published widely on issues related to policy and labour in the cultural and creative industries. He is s Co-Investigator on the AHRC-funded ReCARE TV project which investigates care in the UK’s reality TV sector.

Works Cited

Bectu (2017). ‘Eyes half shut: A report on long hours and productivity in the UK film and TV industry’. Available at: https://members.bectu.org.uk/advice-resources/library/2363

Bectu (2023). ‘Bectu calls for urgent action as television freelancers report unprecedented lack of work’. Available at: https://bectu.org.uk/news/bectu-calls-for-urgent-action-as-television-freelancers-report-unprecedented-lack-of-work

Bectu (2023). ‘Three quarters of UK film and TV workers currently out of work: Bectu survey’. Available at: https://bectu.org.uk/news/three-quarters-of-uk-film-and-tv-workers-currently-out-of-work-bectu-survey

Creative Industries Council (2019). ‘UK TV Exports’. Available at: https://thecreativeindustries.co.uk/facts-figures/industries-tv-film-tv-film-facts-and-figures-uk-television-exports-201819-data

Film & TV Charity (2023). ‘The Strikes May Be Over, The Emergency Is Not’. Available at: https://info.filmtvcharity.com/donate-now

Holdsworth, A. (2011). Television, Memory, Nostalgia. London: Palgrave.

Newsinger, J., & Serafini, P. (2021). ‘Performative resilience: How the arts and culture support austerity in post-crisis capitalism’. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(2), 589-605. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549419886038

Sweney, M. (2023). ‘Channel 4 plans deepest job cuts in over 15 years after TV ad slump’. Available at: https://theguardian.com/media/2024/jan/07/channel-4-plans-deepest-job-cuts-in-over-15-years-after-tv-ad-slump

Wilkes, M., Carey, H. & Florisson, R. (2020). ‘The Looking Glass: Mental health in the UK film, TV and cinema industry’. Available at: https://filmtvcharity.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/The-Looking-Glass-Final-Report-Final.pdf

Youngs, I. (2023) ‘Steph McGovern’s Packed Lunch cancelled by Channel 4’. Available at: https://bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-67157343