28 April 2022 will mark the centenary of the birth of Nigel Kneale – or more properly Thomas Nigel Kneale – a Manx-born writer whose works loom large in my own areas of interest and also across various genres of British television as a whole. And, quite rightly, his televisual legacy is being marked by a one-day appreciation at the Picturehouse in London’s Crouch End, in a season of events at the British Film Institute, screenings during January at Manchester’s HOME and a variety of other regional gatherings to view and discuss this influential author’s body of work.

So, for the uninitiated, quick crash course in Mr Kneale (which is how I still think of him). After his first collection of short stories won an award, this former actor joined the BBC in the early 1950s and made his mark with The Quatermass Experiment (1953), one of the earliest adult serials written especially for television. This six-part thriller drew upon the genre of science-fiction which, at that time, was generally the stuff of Saturday morning chapter serials at the cinema or picture stories for youngsters, and played out the tragic scenario of a Britain’s first space mission primarily by demonstrating the emotive effects on the people concerned with it – notably the project’s instigator, Professor Bernard Quatermass. Mr Kneale then pushed the boundaries again with an adaptation of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1954), and offered two further serials concerning Quatermass – Quatermass II (1955) and Quatermass and the Pit (1958-1959) – which dealt with the Cold War paranoia of infiltration and the horrors of racial cleansing. Nuclear threats formed the basis of TV plays such as The Road (1963) and The Crunch (1964), The Year of the Sex Olympics (1968) looked at a voyeuristic reality-TV solution to overpopulation, Wine of India (1970) also drew upon small-screen stylings for a take on euthanasia, and The Stone Tape (1972) was an un-nerving ghost story for Christmas Day in which the terror of tragic events imprinted themselves in the fabric of a building. The prejudices that fuelled witchcraft were showcased in Murrain (1975), and various animals formed the basis of the un-nerving plays in his Beasts (1976) anthology, following which the final chapter of Bernard Quatermass’ life was recounted in Quatermass (1979). A send-up of extreme SF-fans and UFO-spotters was the basis for the sitcom Kinvig (1981) and one of his later genre works was an adaptation of Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black (1989).

You can get most of these commercially – where they exist – from companies like Network, the BFI and the BBC. Just click on the links.

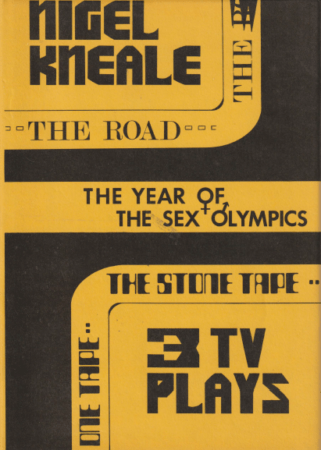

Now, I first met Mr Kneale on the evening of Saturday 12 July 1986. I’d been invited by Dick Fiddy of the BFI to contribute to the viewing notes for a weekend event at the National Film Theatre comprising archival examples of ‘British Telefantasy’, including numerous pieces of Mr Kneale’s work. At the time, I was heavily involved in a fan magazine called TimeScreen (1984-1995) that was edited by Anthony McKay. Anthony’s one of my oldest and dearest friends – the kind of guy who, although he’s lived on the other side of the planet and 13 hours into my future for well over two decades you still chat to and laugh with on a regular basis in the same way when he was 40 minutes’ drive up the M1. Like myself, Anthony was a collector of TV tie-in books… and he’d recently been able to acquire the last two editions of The Year of the Sex Olympics and other TV plays (Ferret Fantasy: 1976). So, clutching my copy, I headed for the South Bank knowing that Mr Kneale would be introducing a screening of The Stone Tape – one of the ‘other TV plays’ in said volume.

Have to admit… I was a bit scared at the prospect of meeting Mr Kneale. In all the printed interviews that I’d read, he seemed rather curmudgeonly… certainly unhappy with the tag of ‘science-fiction legend’ bestowed upon him by genre journals. But he was a lovely man, with a twinkle in his eye and sense of mischief. And, much to my surprise, when I asked if I could interview him for a mere photo-duplicated, small-circulation fanzine about the sorts of shows that he seemed to want to distance himself from at times, he eagerly said yes, here’s my phone number, give me a call, you can come down for tea, etc. etc.

And he gave me this wonderful interview. And he helped me edit and prepare it – even writing me extra bits and pieces. What a lovely man.

He even wrote a letter of comment for the following issue… and didn’t seem at all offended by some of the other far less worthy TV series we’d lumped his words of wisdom in with.

About a decade later when – in my spare time around building databases on a professional basis – I was writing for various magazines such as TV Zone (1989-2008) on an amateur basis, I undertook a lot more research into Mr Kneale’s career. And I found a lot of fascinating stuff – I loved reading the scripts of long-lost radio and TV plays, notions and outlines for unmade projects, really getting a feel for his career as a whole.

And I decided that I’d like to write a celebration of his work. Probably a book or something.

So, I assembled all my masses of notes – the lists of television projects and films and short stories and scripts – and sent them off to Mr Kneale as a starting point for the venture, with the hope that he would help me in this task. And, in due course, he sent the notes back…

… with an awful lot of stuff crossed out.

There were, to Mr Kneale’s view, a lot of things in my data dump that he’d either not been credited for at his request or didn’t see as part of his career… and a lot of the finer detail that, while pertinent to production, wasn’t connected with his narrative work. Certainly a few odds and ends that I’d found interesting to demonstrate his versatility that he felt he’d rather not be remembered for. And he wrote that he felt we “could do better”.

And he was right. Really I should have simply stuck to my professional skills and sent him a Microsoft Access database rather than a book structure.

But this left me with a bit of a problem. I loved the research and I wanted to present this in the detailed way that I felt I needed to in order to celebrate the work of a very nice man whom I admired. Yet, if I did it the way that I wanted to, I’d end up with a book that would please me and might please others… but probably wouldn’t please the one person whose life this all concerned and whose creativity had fuelled the original work.

So, I didn’t do it.

Because I don’t think I had a good enough reason. ‘Because I want to do my book about Mr Kneale my way’ didn’t seem like a good reason. Other people have far better reasons for doing books about anything. ‘To communicate important works in the medium to those who wish to work in it.’ ‘To more widely promote access to archival material.’ ‘To ensure that I can pay the mortgage and feed my children next month.’ These are all excellent reasons. But at that time, I was out of good reasons.

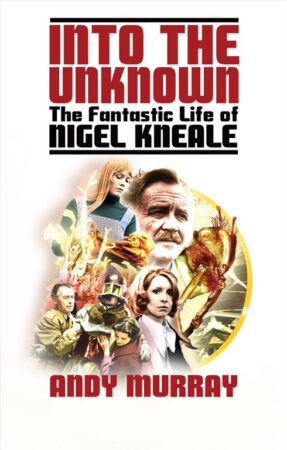

But, as it turned out, it didn’t matter. Because in 2006, Andy Murray wrote Into the Unknown: The Fantastic Life of Nigel Kneale. And this really did the job that I’d had in mind to do but far, far better than I could ever have done it and, clearly, in a manner that Mr Kneale himself felt comfortable with.

Andy’s going to be one of the key players at the Crouch End event on 22 April – and quite rightly so. The main organiser behind this is Jon Dear, one of the people who had been keeping the work of Mr Kneale alive via intelligent discussion on the life-enriching BERGcast podcast which he runs with Howard David Ingham. And if you want to see the quality of inspiration generated by Mr Kneale’s work, look at the people who will be taking part in the celebrations: genre writers and novelists such as Stephen Gallagher and Una McCormack, writer-actor Toby Hadoke who has adapted Mr Kneale’s plays for radio, Dick Fiddy of the BFI, the cultural historian and broadcaster Matthew Sweet… names whom I personally know belong to people who are really great!

So, it’s lovely to see somebody so important to this medium being celebrated so very well. And for all the right reasons.

Thank you Mr Kneale. Thank you for all the amazing serials and plays and films. And for making me stop and think about why I was writing about them in the first place.

Andrew Pixley is a retired data developer. For the last 30 years he’s written about almost anything to do with television if people will pay him – and occasionally when they won’t. Oh, and he was delighted to discover that Mr Kneale had a real sense of mischief. There was an anecdote that he remembers Mr Kneale telling once about the director of a film script he’d written that Mr Kneale recounted with perfect timing in that beautiful, lilting Manx accent of his… and that he daren’t recount here for all manner of legal reasons. But – oh – what a wonderful anecdote.