Sorry if I’m bringing this up, but something is bugging me…

I don’t really know where to start with this, because the longer I think about it, the more it appears that all of the elements are interconnected and, in the end, hark back to how we as television scholars see ourselves and the role we’re playing in the bigger picture of academia within the social sphere…

So, yes, the big questions.

Maybe let’s begin with a personal anecdote: just recently, I found myself searching for a collection of articles because I wanted to update the final version of a contribution manuscript that has been brewing for quite some time now. And, as it turned out, this search quickly and repeatedly had me facing the big and infamous publisher paywall.

Now, one might of course ask why I don’t simply refer this to my library in order to get a subscription of the journal in question. And of course, for those of us who are lucky to be affiliated with an institution that is willing and able to pay for such a feature, this might be a valid option. But my experience has also been that this is where the complications start… let me elaborate:

After having completed my MA at Birkbeck back in 2012, I decided to move back to Hamburg, Germany, to begin my PhD studies – a decision that seemed reasonable at the time because I was also able to get a job there to make a living. With that move, my odyssey through the jungle of access regulations begun, which has since then fed into a personal catalogue of details that I still keep wondering about with the system of scholarly publishing that we as academics still help to perpetuate when we submit articles to a traditional publishing house.[1]

Fig. 1: The Paywall, impressions from Taylor & Francis and SAGE – One PDF to keep for 30 days? That’s 64,-€, please… (side note: they even made a movie about this: PAYWALL: The Business of Scholarship)

Do you, for example, know that many libraries aren’t really given a choice to buy single subscriptions to a particular journal? Fun fact: many journals are only available via so-called “bundles” – a concept that might sound familiar to many television industry scholars. With journal bundles, publishers create pre-packaged and often massive collections that a library can then subscribe to for a similarly massive price that reflects the wealth of journals put in there – but with the accompanying problem that the all-in package price has to be paid even if only a fraction of the included journals is used. In the early phase of writing my PhD, I’ve had many conversations with the librarians in charge of subscriptions at my university, who basically told me that – with television studies being such a minor niche field of study in Germany anyway, and with only a handful of people actually asking for access to corresponding niche journals – the library can’t really justify the investment necessary to buy one of these massive bundles which at the time happened to include three of our discipline’s most important journals to which I needed access to.[2] Five years later (and, ironically, around the same time when I decided to to quit my PhD programme due to a variety of reasons including personal health issues), I was then informed that now the overall bundle had been purchased because enough demand had been generated at the university from the Humanities and Social Sciences so that the library deemed it justifiable to pay the sum asked by the publisher.

These early exchanges then sparked my interest in how deals between libraries and those large for-profit were struck – and quickly, my belief in self-regulation and an open, competitive publishing market crumbled. In brief, the current publication system is an absurdly-lucrative and seemingly self-perpetuating machine that generates enormous profits that make every hard-working regular business blush. Often, these profits are even generated repeatedly, with academics paying twice, or even three times… why? Let me try to sketch this out:

First of all, what for me poses the most fundamental peculiarity in our traditional publishing model is the fact that while we as scholars provide the hot sauce, the key ingredient i.e. our research, we freely and unquestioningly agree to relinquish the right to our content – simply because “this is how it is done”. With every standard publishing contract signed with a subscription-model publisher, we usually sign over the copyright of the final version of our research to the publishing house – for free. This often leads to absurd constellations where scholars are not legally allowed to share their own articles with their colleagues or the public.

And while in some countries such as the UK, the practice of self-archiving preprints (i.e. manuscripts that have yet to be typeset by the publisher but have already been accepted for publication) is gaining ground due to green Open Access mandates [3] enforced by the national funding bodies, this is still not the case in other European countries such as Germany. No wonder, then, that it has become standard practice to ask for help via social media such as Twitter (with the hashtag #icanhazpdf), Facebook (see screenshot), or even has some of us dare and try this magic, but illegal wonder-box everybody keeps talking about, Sci-Hub.

All in all, the underlying problem still looms far and wide: as a result of the traditional publishing practice we keep perpetuating, our research becomes locked in and remains inaccessible to our peers as well as the wider public, which, when considering the bigger picture, is financing our research and academic activities to begin with. And when adhering to the rules of this traditional model, the only solution to this conundrum is money: as I’ve been told by many a publishing house representative over the last few years: “Oh, no problem at all, you are always free to buy access to any article you want…”.

Also, extrapolating from that, I think it is important to ask what principles our existing publishing system is built on: in this still widely established way of publishing, university libraries and other institutions pay publishers via a subscription model. The basic understanding is that the subscription fees are thought to remunerate the publisher for the efforts of securing access to a given journal. Adding to that, they are also used to compensate a publisher’s efforts for adding future articles to the journal’s backlog, which includes bringing new authors to the journal, copyediting, quality control through peer review or similar mechanisms, and the like.[4]

Further to that, a third component had been added to this foundational understanding between academia and publishers: the element of prestige. Since publishing in academia in many fields has developed into a Game of Thrones-esque arena of competitiveness over the last twenty years, measuring of perceived quality – also an issue that television studies scholars might be familiar with – has developed into a metrics-based system that promises objective measuring (whatever that means any more) through the infamous impact factor or similar rubrics. The big publishers then were quick to tie the implicit promise of prestige to a steady increase of subscription costs, but these soon were discovered to also bring about a variety of unintended consequences (for more on this, see e.g. this 2014 LSE blog post on these publishers’ adaptive fee charging strategies, or long-brewing insights into the effectiveness of impact factor-driven research).

Meanwhile, and both enabled and fuelled by the advent of digitization in the last two decades, a counter-cultural shift towards opening access to research, education and academia has grown apace. Rooted in open web culture and corresponding movements around open source, open data and open access, the values of equity and open participation are increasingly seeping into established scholarly practice, with the goal of transforming it towards a fairer and more transparent system.

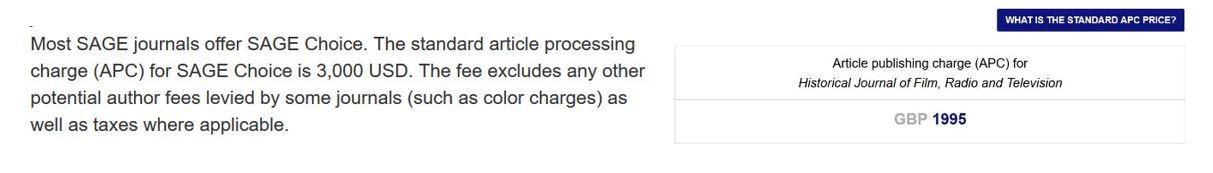

But alas, what we see today is that many of these elements are also co-opted by commercial interests, again and particularly via the big publishing houses: although these now also offer Open Access options, such options have been further monetized and now backfeed into their ever-increasing profit margins (reportedly exceeding those of big tech giants such as Google or Amazon).[5] Open Access for these publishers means asking for usually-astronomical Article Processing Charges (APCs) in order to set the article in question free for anyone to access, and with a corresponding open license attached so as to mark the possibility of free re-use. While the process in itself seems quite reasonable – and I want to make clear here that I’m not arguing that the work done by publishers doesn’t deserve proper and reasonable remuneration – the actual charges are not: usually, particularly the big publishers ask for up to 3,500 GBP for one single article to be made available as open access, while a regular subscription-paid article actually costs between 4,000€ and 5,000€ (2017). And this is where the element of double-pay (which here is usually referred to as “double-dipping”) enters the debate, because this is the point where we as scholars are basically told that if we want to make sure that our research – which we provided for free, will be reviewed by our colleagues for free, and the publication of which has already been paid by the standard subscription system – is actually made available in an open access way, we please be so kind and shell out another 1,000+ GBP for ‘processing this article’. In 2015, RLUK has issued a position paper in which it states that the practice of ‘double-dipping’ has “brought to Elsevier an increase in their revenues […] of over 6%”.

Fig. 3: Article processing charges – that is extra fees to make articles available open access – at SAGE and Taylor & Francis

So, just to briefly recap, my impression of where we stand with traditional publishing:

-

- Content and peer review is usually provided by scholars for free.

- The advent of digital text now means that text production can be streamlined so as to cut costs regarding layout, typesetting, etc.

- The perceived quality as promised by evaluation metrics such as the impact factor has repeatedly been debunked (see e.g. Bosman and Kramer’s excellent discussion in THE).

- The lock-in of scholarly output is a serious problem when we come to think about the social responsibility that we as scholars should strive for – namely accessibility, transparency, and reproducibility – particularly when we are working at and for a publicly-financed institution

- … and when we then demand that our work is made available open access for others to use regardless of their social, financial or political background, big publishing houses come up with a subverted and monetized version of the idea and morale behind open access and ask for exorbitant amounts of money that are completely disconnected from actual expenditure of sustainably running a journal (which – although admittedly not cheap in itself – is conservatively estimated at betwween 500 to 1,500 USD/article)…

Fig. 4: OA publisher Ubiquity Press on sustainable business models in research communication

Opening up television studies?

Television Studies is a volatile field of research and activity, to say the least. Against the backdrop of the larger processes of digitization and globalization, our subject of study has evolved into something both ubiquitous and ever-changing. The simple hypothetical question of “Could you live without television?” has become ever harder to answer and, for many, would translate into a “Could you live without the internet?” due to the now-prevalent and ubiquitous mode of watching television wherever and whenever one wants to via streaming … On the other hand, television studies as a field of academic interest and occupation is facing a variety of challenges that range from Trumpism, looming Brexit and the erosion of the real in debates about fake news and the relevance and contribution of research in and to the social sphere.

Parallel to that, a steadily-growing group of young and emerging television studies scholars are seeking for jobs and tenure in Europe and beyond. My own experience of the last five years as well as those of my peer network indicate that actual chances of finding a job in academia as a television scholar are very small (and close to non-existent particularly in Germany), leading to an over-competitive “market” of young scholars, most of whom know that they won’t find a job, but keep on kicking each other in the hunt for potential “employability” through most publications in high-impact journals that are deemed reputable, lest they might get offered an underpaid job later on.

So, when taking all of the above-mentioned symptoms into account, I wonder: Why do we still keep up with this and willingly enable profit-oriented publishing companies to fine-tune their self-perpetuating money-making machinery on the back of academia? [6]

Also, why do we still agree to be driven by a system of incentives to publish in “quality” journals when the actual validity of “quality” as represented in present-day metrics is known to be largely misleading, to say the least?

I’m not saying that I do have an easy answer to the multiplicity of questions raised here – but I’m convinced that keeping up the status quo is not the answer. And I strongly believe that the tide is turning, because there are many new developments both on the side of academic-led grassroots initiatives as well as on the side of funders, national governments, and supranational institutions, who slowly but steadily adopt new policies that allow for change to happen on national and international levels.

Not to sound too bleak, though, Media Studies – and Television Studies with it – has proven a haven for incredibly amazing new output over the last years, much of which has been showcased on events such as the 2018 Critical Studies in Television conference. Much of that output had also been distilled in papers, monographs and edited collections which, step by step, are put out there by emerging academic-led open access journals such as EUScreen’s VIEW Journal, or the British Association of Film, Television and Screen Studies new journal Open Screens, which is hosted with the Birkbeck-based Open Library of the Humanities, and book publishers such as OBP and Ubiquity Press that are now collaborating under the roof of the ScholarLed initiative. Also, Media Studies scholars have begun to seize many of the possibilities offered by the digital sphere, including social media and blogging as well as collaborative tools and new and intriguing ways of analysing media offers.

For those of us who want to connect with peers online, there are social networking platforms such as Humanities Commons – come and see our Television Studies group! – that offer a variety of services such as having your own WordPress blog for free, without the advertising hassle of commercial offers such as academia.edu or ResearchGate (see Sarah Bond’s excellent Forbes article on why leaving these commercial platforms behind is the necessary thing to do). Also, and just recently, Dutch media scholar and Open Access proponent Jeroen Sondervan announced the launch of a discipline-specific open, non-profit platform by the name of MediArXiv. There, “media, film, and communication scholars [are able] to upload their working papers, pre-prints, accepted manuscripts (post-prints), and published manuscripts. The service is open for articles, books, and book chapters.” (project statement, 2019) MediArXiv [7] is backed by the Open Access in Media Studies initiative, which is, among others, linked to NECS, one of the two major European media and communication studies networks next to our beloved ECREA network. The platform is the result of continued networking and collaboration between OA advocate Sondervan and a variety of stakeholders, including long-term open access advocate and esteemed host of Film Studies For Free, Catherine Grant, Professor of Digital Media and Screen Studies at Birkbeck, University of London, and Jeff Pooley, Associate Professor of Media & Communication, Muhlenberg College. Further to that, Jussi Parikka, Professor of Technological Culture & Aesthetics, University of Southampton, and Leah Lievrouw, Professor of Information Studies, UCLA have now joined the MediArXiv steering committee.

Open Practices for Media Studies

Fig. 6: Open Access in Media Studies: directory of open access journals, publishers and funding opportunities

What I hope to have been able to highlight, if only superficially, with the last few paragraphs, is the existence of a broad spectrum of academic-led alternatives to the status quo. Almost all of these strive for nothing less than a cultural change: away from profit-based, locked-in research, towards an open understanding of academia that re-centers its values on the – still somewhat utopian-sounding – elements of equity, open sharing and a participatory culture in which the field of television and media can help explain, and thus counter, the earlier-mentioned threats of ignorance and narrow-minded world-view.

Now, if these last few paragraphs maybe helped spark your interest int the promise of open access and the underlying culture of openness, I’d like to point you to one particular piece of thought, a collaborative document in which an international group of scholars sketch out possible ways forward – the Foundations for Open Scholarship Development.

There’s so much that we as a community of scholars can do – let’s not simply settle for the status quo that is presented to us by profit-driven businesses.

Tobias Steiner has studied in Hamburg and London and holds an MA in Television Studies from Birkbeck, University of London. For the past seven years, he has been working as a research fellow in the field of open science and education at the Universität Hamburg’s Universitätskolleg Digital. He is currently the YECREA representative of ECREA’s Television Studies section and has published on a variety of topics, ranging from questions of authorship in Game of Thrones to the transnational renegotiations of Nordic Noir (in print, 2019). See his ORCID profile for further information and list of publications.

Footnotes

[1] When addressing these, I’m mainly referring to the Big Four, i.e. Taylor & Francis, Springer, SAGE and Elsevier – smaller publishers are, at least in my experience, usually much more reasonable and willing to adjust to the needs of the customer when it comes to finding solutions that are suitable for both the publisher and the author.

[2] Including our beloved Critical Studies in Television, which only a few select libraries in Germany had access to during my first years of enquiry. And when we now take this situation and exchange the location of where this is happening to, say, countries or regions that are deemed more remote such as Greece or the Middle East, we can see that this kind of access model is quite exclusive, to say the least.

[3] See e. g. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/posting-to-an-institutional-repository-green-open-access

[4] I have to say that this, of course, is a rudimentary outline at best. If interested in further details, make sure to read e.g. Lawson et al., 2016.

[5] Buranyi 2017 writes “In 2010, Elsevier’s scientific publishing arm reported profits of £724m on just over £2bn in revenue. It was a 36% margin – higher than Apple, Google, or Amazon posted that year”. Newer numbers suggest a ever-continuing rise in profits: for 2018, “the Amsterdam-based publisher reported an all-but-unchanged profit margin of 37.1 per cent.” And while what counts as real profits is often not easy to pin down “due to the disaggregation of the market” (Eve, Lawson and Tennant, 2016), the publishing houses’ business practices have been subject to widespread criticism: Björn Brembs, for example, asks “Why can Elsevie keep insulting scholars without consequences”, while Tennant and Brembs have just recently filed for a formal complaint with the European Union’s Competition Authority about “anti-competitive practices of RELX Group [the conglomerate owning Elsevier] in the scholarly publishing and analytics industry”.

[6] For a cultural history of today’s profit-based publishing business model, see e.g. Buranyi 2017.

[7] arXiv (pronounced “archive”—the X represents the Greek letter chi [χ]) is a repository of electronic preprints (known as e-prints) approved for publication after moderation. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ArXiv