- https://rts.org.uk/article/euryn-ogwen-1943-2021

- https://nation.cymru/news/giant-of-welsh-broadcasting-euryn-ogwen-williams-passes-away/

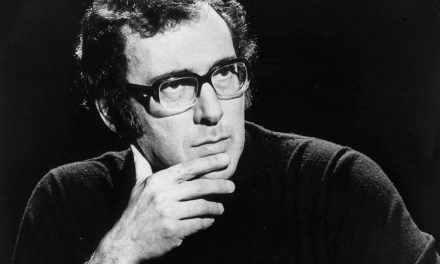

For anyone who had dealings with Euryn, he was also a stupendously positive human being. To have a chat with Euryn was to enjoy the brilliant sunshine of his undivided attention, and to emerge re-energised and with a new view on whatever project or aspect of life that had been raised. In Welsh broadcasting – an often frustrating and difficult area of cultural life – Euryn lifted the clouds, gave confidence and made the seemingly impossible, possible. These gifts were perhaps most apparent at the beginning of S4C, and it this time that this interview recalls.

PART III

S4C was launched on November 1, 1982 – the night before Channel 4’s launch – and Euryn Ogwen, as head of programmes was responsible for constructing the new channel’s first hour. I was ten years old, and watching the first hour in the office of my father’s television company, Screen ’82, in Aberystwyth. 30 years to the day, Euryn and I met at the National Screen and Sound Archive in Aberystwyth to watch the channel’s first hour once again, and to decipher what Euryn called, it’s ‘hidden messages’. The conversation that follows seeks to dig beneath the surface of the first hour to analyse the roots of the channel, and to reflect on the thinking, the preparation, and the random elements that led to the composition of the first hour of S4C.

This third instalment takes us from the special relationship between Channel 4 and S4C, to the precarity of some of the deals made to get the channel off the ground…

Now the hour went on to explain our relationship with Channel 4. This shows how close Owen and Jeremy Isaacs were. Jeremy has retired to somewhere very remote, but he attended Owen’s funeral, having to travel for two days, on the train and staying here and there. This bit before the chat between the two shows the kind of programmes that were being shown on Channel 4, but that we were showing them as programmes that would be on S4C because of Channel 4.

DSJ: That is a portrait of a large Channel 4 and a small S4C, and that Jeremy Isaacs speaks Welsh is astounding…

EOW: … and this is in 1982, three years after the failed referendum for a Welsh assembly. In that context…

DSJ: … so this was in the context of the vote in 1979, in the context of Thatcher and the Tories in the early 80s, in the context of the newly elected Tories changing their minds about S4C, in the context of Gwynfor Evans’ hunger strike[1]; it’s quite a combustible time, with fears over violence and the IRA etc?

EOW: The context was frighteningly dangerous, and if we had not gone ahead emphasising that we were part of something larger, that would perhaps have been a problem. We were judged for doing so, for getting Jeremy Isaacs on the first night at all. But in a way that’s why we had to do it. That was our biggest problem, that we were there to provide a television service, not to realise Gwynfor Evans’ dream – it was to be a TV channel, and if it does all the things it should, the desired outcomes would follow naturally. But it was foremost a television channel, and we were part of a partnership, and part of that partnership was this man who was willing to appear on S4C, on a small monitor, speaking Welsh.

DSJ: is it fair to say that many of the messages contained in the first hour were there to dampen the sparks that had arisen during the campaign for the channel?

EOW: It was about telling a nation, that perhaps expected more, that this was the reality – this is what you are getting. But also that we were part of something bigger, and that we had friends everywhere. Right from the start we wanted to give the impression that we were a partnership with another TV channel, and not an experiment, we were something that would last.

DSJ: Was there a real feeling that S4C would last for three years and then disappear?

EOW: Certainly, many people were banking on it. Politicians – Labour ones in particular – and the BBC. It wasn’t dangerous for Jeremy Isaacs to do this, but he certainly did not need to. Every month we went to London to their commissioning meetings, and we told them what we had commissioned, and they told us what they had commissioned, and they showed a lot of our stuff with sub-titles at the start! We gave them material for nothing, and Jeremy Isaacs was very keen on rural films and things of the sort, and they showed them in Welsh with subtitles.

If there was a very risqué bit going out, they would phone us on the night and say ‘be careful on this one you can edit the beginning of part two because we think we might be in trouble on it’, but we never did because the instinct was – the old ITV thing – that is you broke ranks you put them in a hole. So, if there was something libellous, it went out with us as well. If they were willing to pay, that was OK. But we were not going to pull the rug from under them.

DSJ: Was there a patronising element to this advice?

EOW: No, I think it was friendship. Paul Bonner was Channel 4’s head of programmes at the beginning and he and I were friends. He could receive S4C because he had a house near Exeter, and the signal came over. So, on the weekend he would see S4C, and he would be on the phone saying ‘a bit rubbish on Saturday night!’. It was quite a close relationship, and we got to go to these commissioning meetings, which were at such a high level. They were allowed to do something different at Channel 4, but we had to be careful, and that we didn’t do anything different, especially at the start. They were the ‘alternative’ and we were ‘the only’.

DSJ: Did they realise that?

EOW: Yes, they did. They understood perfectly. Jeremy Isaacs often came to spend the night, arriving around 5pm, and then sat through the evening with Owen, with food being brought in. And we would discuss where we were heading, were there dangers we should avoid? Were there things we should do more of? It was a special relationship, and very different to the traditional relations between broadcasters.

The other thing this conversation signalled was – and as much to Owen as anyone else – S4C was not a regional broadcaster, it was a network broadcaster, but that the network was in Wales. And then we were part of a network with Channel 4, deciding which programmes went out when. It was a partnership. Often, we went out live with them, if the programme was appropriate. But you could not do delayed broadcast you see – the technology was not there – all you had were VTs. We recorded everything that came down the line from Channel 4, but we couldn’t start it 10 minutes later, it was the middle of the 80s before we could do that. Either we were with them live, or it went out on another night.

DSJ: So, it was all live in a way – that is to say someone was pressing the button, someone was watching it go out.

EOW: S4C was live all day, because of the technology. Every programme went out on a tape from headquarters.

DSJ: Did you feel there was a tension between the programming coming from you, and that coming from Channel 4?

EOW: That was inevitable. We were looking for a mass audience, and Channel 4 was looking for the niche audience. And there was a feeling that we needed to represent all that in the first hour – including a taste of the difference between S4C and Channel 4 – so they could know exactly what to expect.

DSJ: Do you have any idea of how many people watched the first hour?

EOW: Yes, there are figures – about 200,000 under the old way of measuring. That was quite respectable. Lower than BBC1, but higher than BBC2, it was quite respectable.

Now we are moving into the footage that shows the choice of programmes, emphasising that there were also popular programmes. We recorded this the day before launch, in the afternoon. Here is Alun Armstrong in the theatrical production of Nicholas Nickleby. These presenters were criticsed; the line with these two were that they were new presenters – well, Sian had done a bit of Radio. Rowena went on to become a producer after two years, and she still produces – she was from the North, and Sian from the South… listen to this then…

DSJ: What is this?

EOW: …wait…

DSJ:… I didn’t expect that!

EOW: He’s not the only one! When we decided to sell Super Ted in Cannes, we needed to get a stall there, and the stall Chris Grace and I knew of was TWI (Transworld International), McCormack’s company. They looked after all these stars, and then they made us an offer – ‘would you like Bjorn Borg to say good luck to S4C?’ – why not?

DSJ: Who produced the clip?

EOW: TWI! When all this stuff came from TWI, we knew that they had done something, but we didn’t know what the content would be! So, we had Bjorn Borg, and if you carry on you’ll get Miss World say best of luck to S4C!

DSJ: So what was the connection between S4C and TWI?

EOW: They, in truth, were the agents that sold Super Ted. Thanks to them we reached all the territories that bought Super Ted. We had a corner of their stand in Cannes, and they did this so we stayed with them as agents – you couldn’t refuse after that! So, what we got were mini-docs with people who claimed a connection with us, saying good luck to S4C! So, that was totally bananas.

DSJ: Yes it is – I am expecting Dewi Pws [2] to jump out at any moment and start playing tennis with Bjorn Borg. This looks like another sign to me.

EOW: It was a sign. We had no problem in including it because it reinforced the message that we weren’t a small channel, we are out there, connecting with the world, don’t restrict us.

DSJ: So to some extent that goes with Channel 4’s message, with alternative sports – Bjorn Borg rallying! – and also there’s the fact that Borg is speaking in Swedish to Wales, not through the medium of English.

EOW: Once this material arrived, we had the discussion – ‘are we just going to have the section when Bjorn Borg says good luck to S4C? – but to hell with it, why not let them have their mini doc as well.

DSJ: Was that somewhat accidental?

EOW: Totally! We never sat down and said ‘oh, we really need Bjorn Borg’! Then we got Terry James [3] saying ‘hwyl fawr S4C’. It’s likely that Terry came through TWO as well. We certainly wanted to establish Wales’ place in the world, that Wales had gone out to Hollywood and succeeded. That was deliberate. And now we have Miss World…

DSJ: Is she going to say a word?

EOW: Not straight after winning – that was not the first thing that came to her mind!

DSJ: Yours and TWI’s choices are interesting – Bjorn Borg, Miss World, Camelot – they are mainstream, but with the Welsh theme in Arthur, and they give a feeling of what was to come – after all Terry James is not a famous avant-garde theatre director – and that this impression is part of S4c’s identity as supplying something for everyone?

EOW: That’s it, to be popular as well. I think the clips were important in distinguishing us from the BBC. And we wanted to show we could be irresponsible.

DSJ: Was that part of the deal with Channel 4?

EOW: Yes it was. Onwards. More adverts now; no actors of course; and he was the other one to do his own adverts, Ken Rogers from ‘Hyper Value Value’ [4]. Poor creature has died since, a real showman. Now out we go…

Well, this is a bit more obvious, there must be some significance to this.

DSJ: Again, it’s somewhat absurd, and perhaps an alternative rural portrait. But the song is traditional, there is a female choir, there are some goats, but no explanation, no voice over, no graphics – it’s a strange take on something traditional – am I reading too much into this?

EOW: It’s possible that we thought we need to come home after some of the things that have been included in the hour so far. Also, this might have been another example of how to deal with the problems of breaks and adverts.

DSJ: Rowena’s words after the song, about the possibility of other similar musical breaks and S4C’s readiness to listen to its audience – that this was a DIY insert – goes along with your feeling that this insert was designed to bring S4C back to its core audience.

EOW: Exactly.

— END OF PART III —

Dafydd Sills-Jones is Associate Professor in the School of Communications at Te Kura Whakapāho, Te Wānanga Aronui o Tāmaki Makau Rau (Auckland University of Technology). Before taking up this post in 2018, he was Lecturer in Media Production Cultures and Director of Postgraduate Studies in the Arts Faculty of Aberystwyth. Dafydd is co-editor of Peter Lang’s ‘Documentary Film Cultures’ book series, is on the editorial board of Media History (Taylor & Francis), The International Journal of Creative Media Research (Bath Spa University), and is a member of the International Association for Minority Language Media Research (IAMLMR).

Web: https://academics.aut.ac.nz/dafydd.sills.jones

Footnotes

[1] Plaid Cymru’s first MP, Gwynfor Evans, had threatened to fast until death unless the election promises, of both Labour and Conservative parties, at the 1979 election to establish a Welsh channel were not realised: https://bbc.com/news/uk-wales-12062288

[2] Dewi Pws is a lengendary Welsh language entertiner, working across songwriting, musical perfromance, comedy sketch writing and dramatic acting: https://swansea.ac.uk/graduation/honorary-awards/2018-archive/dewi-pws/

[3] The clip refered to here can’t be repordued due to copyright issues, but hsows an interview with Terry James, the msuical directors of the broadway production of ‘Camelot’, starring Richard Harris, in 1981: https://nytimes.com/1981/11/16/theater/stage-camelot-is-back-with-richard-harris.html

[4] Hyper Value Value was an early example of a low-cost ‘bucket shop’ which had several sites across South Wales.