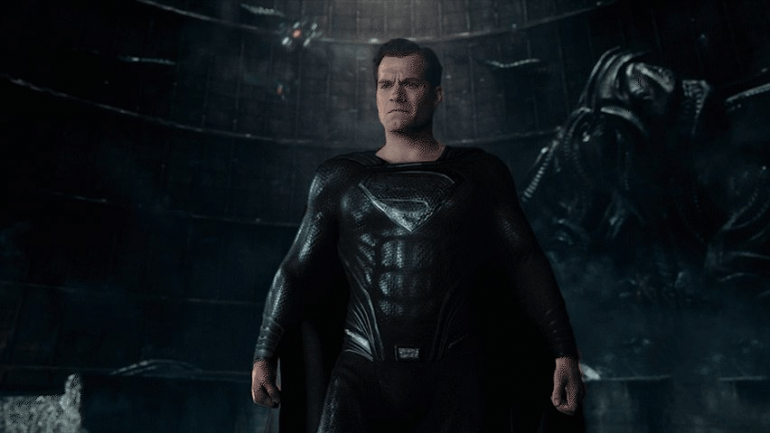

So, when I started to think about this post, I initially planned on writing about Zack Snyder’s Justice League, that sweeping superhero epic that dropped on HBO Max this past March. Aside from the fact that the very idea of the film had been a holy grail of cinematic possibility for Snyder fans and comic-con attendees for years, the movie itself is a rich tapestry of slo-mo shots, daddy issues, deep-seated guilt, and widespread DC gloom. (Heck, even Superman is dressed in black.) For whatever hope comes out of the film’s final battle, Bruce Wayne’s unsettling “Knightmare” at the end anticipates a post-apocalyptic future as well as an alternate reality of Snyder sequels, enough to fuel our imaginations with visions of unmade movies for years to come. The Snyder Cut also raises all kinds of interesting questions about authorship and authority, as it expansively retells and reimagines the story that Joss Whedon told in his 2017 film, which Snyder never saw and which was, in itself, a reworking of his original plan for Justice League. [1]

Before I could get going, though, I stopped because this website is, like the hard copy journal, specifically devoted to Critical Studies in Television—not film. So, this just didn’t seem like the place for an essay about a movie. Or was it? After all, I watched the film on a television. Because of the pandemic, I really had no choice. So, wouldn’t anything on TV right now be fair game for CST?

There has always been a great divide between television and film—or at least the perception of one—for all of the visual and narrative similarities between them, the evolution of cinematic TV, and the development of multiyear film series arcs, like the Marvel phases or those Star Wars films, which even call themselves “episodes.” In an intriguing Vulture discussion of Small Axe last fall (‘Small Axe’ and the Movie-Vs.-TV Debate That Won’t Die (vulture.com)), TV critic Jen Chaney openly bristled at “this long-held notion that film is the superior, true art form and television is for garbage people who do not understand cinema,” and I feel her pain here. To the extent that film and television are different media productions, film and television criticism seem to be viewed as more than just different genres or disciplines; they are different ways of life, as her description of “garbage people”—with all of its social implications—suggests. Film critics go to school for years to learn about the history of cinema. TV critics go to their dens to watch their favorite episodes. (That may be changing, though, as graduate programs in television studies, as opposed to production, may be on the rise.) Film critics sit in air-conditioned theaters with reclining leather seats and consider the existential angst of beleaguered protagonists set against the backdrop of the modern landscape. TV critics watch car chases in food-stained La-Z-Boys and think about the crashes. Film critics eat caviar and drink cognac. TV critics eat pizza and drink beer. Film critics perspire. TV critics sweat.

So, maybe not all of this is true. I don’t drink beer. But you get my point.

The fact is that film critics and TV critics don’t always see themselves in different camps, as people who focus primarily on television often write about film and vice versa. In some cases, when TV shows cross over into films, the critics who follow those shows are understandably inspired to write about them and to bring their background and their knowledge of the characters’ origins to bear in their analysis of those big screen storylines. And given their expertise, why wouldn’t we want their perspective on those films—or, for that matter, on any film at all? If Martha Nochimson decides to write on Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me or the films of Wong Kar-wai, the Net shouldn’t break, peel, or crack, and the SCMS or the PCA shouldn’t be sending out cease-and-desist letters, any more than they would if A.O. Scott comments on Cedric the Entertainer Presents. To my knowledge, the MLA didn’t ban literary critic Stanley Fish for his book-length study of The Fugitive.

Nevertheless, the stigma about TV and TV criticism persists. Since I mentioned Twin Peaks, in a 2017 Vox piece (Twin Peaks: movie or TV show? – Vox), Emily VanDerWerff examined the extensive tug-of-war between critics to alternately label Lynch’s revival as a TV show or a film. As she noted, in drafting their list of the best films of the year, Sight & Sound and Cahiers du Cinema, two of “the most intellectually rigorous film journals, placed Twin Peaks: The Return within their top two.” Although Sight & Sound expanded their voting to include any and all “screen things,” which would allow for TV, they “still dubbed [their] list the ‘best films’ of 2017,” VanDerWerff pointed out, “and [this] labeling is what kicked up the kerfuffle.” Was this an attempt on the part of S&S’s editors to co-opt Lynch’s series as one of its own, in spite of the show’s obvious origins? Was this, perhaps, the highest praise that they could give Lynch, to elevate his work to the “superiority” of film, rather than to accept it as a product of television? Or was it, as VanDerWerff ultimately hoped, a sign of how such rigid distinctions were wearing away, all blurring and blending into what she cleverly called “the great, mushy mass of stuff that we consume on screens of some size or another”?

Beyond the necessity of watching film on television at the moment, the very definition of a film vs. a TV show continues to melt into that “mushy” consistency, as technology continues to change just how and when we watch what we watch. Although TV shows may have been made for episodic viewing, binge-watching challenges the idea of individual episodes, just as streaming allows us to break longer movies into more manageable segments or dare-I-say episodes themselves. Not only is the Snyder Cut divided into separate parts or chapters, but, at just over four hours, it almost demands multiple sittings to complete. Slap a title sequence onto those parts and some credits at the end, and you’ve got something akin to a Justice League miniseries.

Since I’m on the subject of superhero films, Marvel complicates those definitions even more, as their feature films have now given way to a number of TV series, which will, in turn, set up future films. The narratives of WandaVision and The Falcon and the Winter Soldier are clearly written with television in mind. Nonetheless, as we follow those characters back and forth from film to television, those divisions seem to bleed, bubble, and ooze, like so many leftovers in the microwave. We’re following actors and characters; how we see them may not mean as much as that we continue to do so and to invest in their storylines.

Intention, I suppose, could have something to do with how we consider that “stuff.” If the story was meant to be consumed as an episodic narrative, as opposed to a long-form one, then we could call the former “television” and the latter “film.” If I go back to what Chaney said in the Vulture article, these definitions clearly matter. “How one views them,” she argued, “is completely irrelevant.” For her, our need to reorganize them, regardless of how we do it, takes a backseat to how and why the object was created in the first place, and this could be true for critics on either side of the (movie) aisle. Having grown up with these categories, we all may struggle to see them go, if only to make sense of what we are seeing and doing when we are watching these “things.”

While we might believe that attitudes are a-changin’ since the Twin Peaks “kerfuffle” of 2017 and that all critics are equally served at the smorgasbord of culture, Ian Greaves’s recent column on Sight and Sound’s addition of television reviews, “after an absence of almost 30 years,” suggests that old stigmas, like Bruce Willis, die hard. According to Greaves, instead of using those reviews to reexamine its scope, S&S’s nod to TV comes off as rather forced, as they “only [seem to be] covering television because the cinemas are shut.” So, maybe S&S was, in fact, trying to claim Twin Peaks as one of its own—as a film only disguised as a TV show.

If the Vulture conversation is any indication, we still have a long way to go in terms of how we think about these objects and what can be said about them, as even the language reaffirms an inherent prejudice toward TV. Film critic Alison Willmore was quick to call out Marvel Studios head Kevin Feige for his “deranged description of The Falcon and the Winter Soldier”; again, the highest praise that he could give the show was to compare it to a Marvel film and to distinguish it, Willmore charged, from what it actually was: “a miniseries.” Quite often, isn’t this the way that compliments about TV go, to compare an episode or a series to something more aesthetically acceptable?

Although some films, like the new Wonder Woman movie, have dropped on television first, so many studios are still sitting on their productions—like the egg-laying goose in Aesop—determined to release them on the large screen and to realize their dreams of box office gold. Who knows how long it will be, though, before movie-goers are comfortable enough to take them in that way? If reaching an audience is a priority, TV undoubtedly will be the way to go, and the studios will need to see themselves as part of the medium or “the mushy mass,” not aside from or above it.

All of this brings me back to Snyder’s Justice League, to Bruce Wayne’s bad dream—which has rapidly become one of my own—and to my original question, as a test case for these larger issues. Should this film be the stuff of TV criticism, or should we, instead, move toward the criticism of stuff?

Douglas L. Howard is academic chair of the English Department on the Ammerman Campus at Suffolk County Community College. He is the co-editor of Television Finales: From Howdy Doody to Girls, co-editor of The Essential Sopranos Reader, and editor of Dexter: Investigating Cutting Edge Television.

Footnote

[1] For more on the Snyder Cut’s fascinating backstory, see Anthony Breznican’s “Justice League: The Shocking, Exhilarating, Heartbreaking True Story of #TheSnyderCut” in Vanity Fair (Here’s the link: Zack Snyder’s ‘Justice League’: The True Story of the Snyder Cut | Vanity Fair). Sean O’Connell also discusses the enormous impact of fan support for the film in his new book, Release the Snyder Cut: The Crazy True Story Behind the Fight that Saved Zack Snyder’s Justice League (Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2021).