by Ian Greaves

One of the many peculiarities of life in lockdown has been to witness the turmoil it has created for Sight and Sound, a magazine used to reporting from festivals and film sets around the globe. Like the rest of us, they have had to adapt to a different way of living. To their sometimes evident horror, this now includes television.

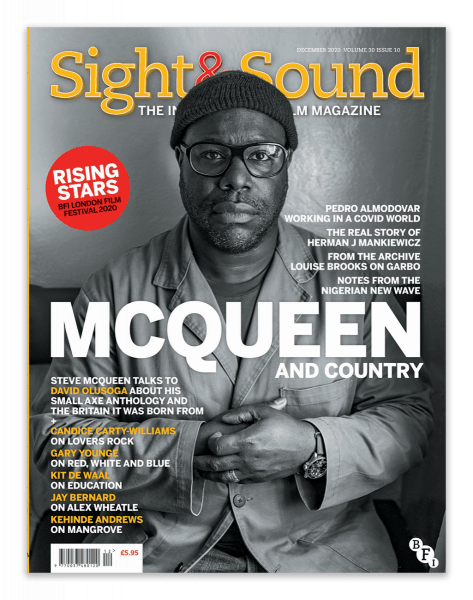

Fig. 1: BFI’s Sight & Sound, December 2020 issue: on Steve McQueen’s anthology series Small Axe (BBC, 2020)

The pandemic hit just as a new editor was put in place, and one can hardly envy Mike Williams’ bad fortune when wanting to make his mark. He has done a good job in difficult circumstances. It’s actually impossible to tell how much of S&S’s television coverage over this past year has been part of his long-nurtured masterplan, or a means to an end. Either way, extended reviews of new television have returned after an absence of almost 30 years and the small screen has even made the front cover, which is simply unheard of. Of the nine issues so far produced under Covid, four had television on the cover: I May Destroy You, Can’t Get You Out Of My Head, Small Axe and The Underground Railroad.

This is obviously delightful, but what has concerned me is the underlying attitude of the place of television within the magazine’s more general outlook. Too often, reporters refer to television with a purely cinematic sensibility, and comment on the motives of its makers as though ‘long form storytelling’ was a whole new discovery and that they were only dabbling in television because they couldn’t sell an eight-hour film to the studios.

There’s also a tangible air in some pieces of ‘we’ll get back to the proper stuff once this nightmare is over’, that they’re only covering television because the cinemas are shut. To me, a red-blooded television obsessive, Sight and Sound still feels like a fairweather friend. The recent readers’ survey, which really irked me, mentioned television just once and when it did it referred to “high end” television only. One editorial even concluded with the sentence “Viva cinema (and heavyweight TV)!”

Let those quoted phrases ring in your ears, dear CST reader. There is a definite sense of territorialism here. And it set me thinking that we have actually lived through an extraordinary time for television, all of it, without a magazine fit to reflect the moment. Film culture’s ability to absorb and reclaim what interests it about modern television – be it Twin Peaks – The Return, Small Axe or We Are Who We Are – and reject the rest, has left us with a wider television culture which, as usual, has an insufficient UK critical platform and a lack of champions in the mainstream press who are too often more passionate about the US output anyway.

There are even fewer efforts to engage with the industry and politics that shape UK television, which was once so important to the entire ebb and flow of the conversation as it evolved in the 1960s and 1970s. The leading critics, even those working on the tabloid newspapers of the day such as Peter Black of the Daily Mail, were fully engaged in questions of control, censorship, funding, and how this affected what reached the screen. Media reporters such as the late Peter Fiddick of the Guardian were brilliant at letting us, the viewer and reader, into this world. For a healthy television culture, that kind of engagement is just as essential as a tweet-along of Strictly Come Dancing or Question Time.

So I would say that Sight and Sound did well to cover television during the past year, but it missed the big story. 2020 was the most interesting year for television of my lifetime (full disclosure: I’m 43) and it’s really not too difficult to mount that argument.

Covid exposed the inner workings of television like no other. It shifted media literacy for millions, and changed what was acceptable in screen language – possibly for good. Many things which had been bubbling under the surface – self-shooting, citizen journalism, the grammar of vlogs – became a norm. Creatives did what they always do and worked within the framework and limitations given to them, such as when Emmerdale was the first UK soap back and made a run of small-cast episodes with an unstated social distancing between actors. Panel show Have I Got News For You evolved in public, eventually settling on a method of production over the course of a series. And when Anthony Hopkins was interviewed recently on A Late Show with Stephen Colbert (19 April 2021) and the vision froze for at least ten seconds, it went unremarked (see video at ~10’23”). The interview continued. The viewer understood.

The public has a heightened sense of the medium’s construction because of a combination of what is given to them and what is now absent. This could express itself when a political reporter interviews a minister with a long microphone on College Green, or when a comedy show airs without a studio audience. But there are unseen stories, too, which I think can add to the appreciation of the hard work of television makers, such as the delightful detail that Newsnight was moved from 22.30 to 22.45 so that there could be a 15-minute window to clear out and make safe the Ten O’Clock News studio which they had to share from March through October 2020. It’s a small story, but a good example of precisely why the schedule has been bent out of shape.

And look at one other scheduling factor which will be close to the heart of any CST reader: the extraordinary sight of Blackadder II repeats on BBC One at 9.30pm in 2020. A consequence of a drought of programming, no doubt, but I ask you this – did the sky fall in? I’m unsure if The Road to Coronation Street (BBC Four, 2010) yet qualifies as archive television, but that also went out in peak-time on ITV – a channel previously allergic to repeats older than a loaf of bread. BBC Four finally expanded its repeats beyond Top of the Pops and, while this will now become more common due to other cost-cutting issues, it does mean that the general public may happen upon older programming without having to wander too far up the Freeview dial. For me, reading the Radio Times schedules became a kind of code for the condition of television production through the second and then third national lockdowns.

We need engaged reporting of television more than ever, not just to explain this surface detail, but because of the potential threats to production as we emerge from a period in which viewers have become used to a lack of high production values. There will be a need to return to spectacular eye-catching shows, sure – Amazon’s extraordinary spend on the new Lord of the Rings series demonstrates that – but ask documentary makers or comedy producers their view, and you will discover real fears that commissioning editors will see this as an excuse to cut budgets further. Will writers’ rooms survive to anything like the same degree, and what is the persuasive argument for a proper studio shoot when corners can be cut and the viewer has become immune to the shock of lower quality?

If Sight and Sound, or indeed any publication which purports to have a genuine interest in television, wants to cover it well, then they should be dealing with this. All of it. The story of television in 2020 was not the ‘prestige’ shows – many of which had been largely shot prior to March anyway – but the programmes which continued throughout, come what may. We shouldn’t dismiss them because they’re not cinematic enough. We should value them and protect them, and that starts by talking about them.

Ian Greaves is a writer and researcher who has published widely on television and theatre history, and has edited collections of the work of Dennis Potter and Dr Jonathan Miller. He spent the first lockdown as consultant on the BBC Four documentary Drama Out of a Crisis: A Celebration of Play for Today.

Wonderful read – very, very much appreciated. Once again, makes me wish that more publications devoted solely to television were practical and available in the marketplace to look at the medium from many different angles.

Thanks for such a great piece! 🙂

All the best

Andrew