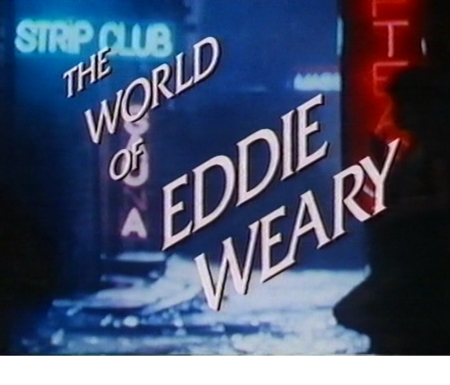

Now, I’m sure that, like me, you have fond memories of The World of Eddie Weary, the massively popular private investigator series of a few decades back.

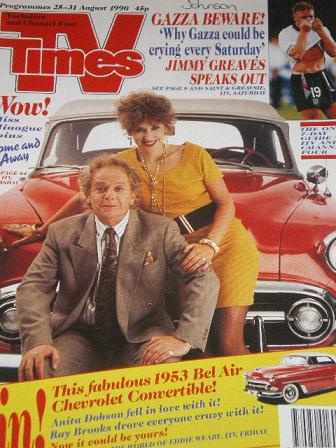

What do you mean ‘never heard of it?’ For three consecutive years it was named as Most Popular Series on Television, triumphing over both Death Squad and The Loveable Crooks of the Costa Brava at the TVTimes Awards in 1990. How can you call yourself somebody with an interest in the history of British Television and not have heard of it?

Well, of course you’ve never heard of it. Unless you were one of the 7.17 million watching ITV between 8pm and 10pm on Friday 31 August 1990. Or one of the two dozen people who tuned into Carlton Select on random dates from 1996 to 1998. A six-part series was mooted but never happened, and it was even nominated for a Drama International Emmy in 1991. I was there on Friday 31 August 1990, and I’d had the foresight to unwrap a new VHS tape for the occasion as well because I had a good vibe about this one.

The World of Eddie Weary (1990) was a one-off TV movie (and potential pilot) about the making of a TV series called The World of Eddie Weary. And a TV show about making a TV show… oooh, that’s a tricky thing for me to resist. And, furthermore, this was by Roy Clarke of Last of the Summer Wine (1973-2010) fame, so it was likely to be good. In fact, it was probably going to be another attempt at his earlier series Pulaski (1987), a comedy-drama about the making of a rather inept transatlantic action show in the UK where the boundary between the drunken, womanising star and his priest-turned-PI character became blurred.

And, yes, that’s what this was. Shot for Yorkshire Television by Fingertip Films around Leeds and Bradford in May 1990, The World of Eddie Weary is a typical, reassuring primetime drama with a flawed central character who helps others. His company East West Investigations – which consists of just him – operates in the multi-cultural Yorkshire city of Bradford, depicted as both the home to the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, and also as an environment where a lunchtime visit to a pub will reveal turbaned Elvises gyrating their hips, or Maisie from Cleckheaton and June from Kippax performing amateur striptease on their way home with their shopping.

Eddie narrates his own tales as a “Chandler-type hero”; cleaned out by his ex-wife, he lives in his pokey office, can’t afford to pay the phone bill, and drives the steep city streets in a multi-coloured patchwork Datsun with a dodgy battery. He loves 1940s Big Bands, 90 proof Polish vodka and a few too many little cigarettes. He deals sympathetically and discretely with first-time shoplifters if they return their spoils, and allows a couple to complete their rural lovemaking before delivering a writ. “The viewers like him,” explains Madge, the show’s ruthless producer, “a lonely guy doing a lonely job and giving it the best he’s got.” Eddie’s down-at-heel integrity and dogged persistence for those who have no other source of help for their problems places him in the same league as Frank Marker from Public Eye (1965-1975) or Eddie Shoestring from Shoestring (1978-1979).

Eddie himself is played by Alex Conway – and Alex is very different to Eddie. Neurotic, loud, arrogant, egotistical, and paranoid about the hotel staff of his penthouse suite ironing his trousers because of their short inside leg, he compensates for his self-conscious lack of physical stature by driving a flashy, red 1953 Chevrolet which is “two streets long” (“Flash car for you Eddie!” shouts one fan). Trying to keep both a drink problem and a barracuda of an ex-wife behind him, he is a bitter celebrity, only really interested in seeking relationships with women whom he classes as “good-looking” but continually chatting up what he calls “talent” to gain nothing more than a request for an autograph. Storming off locations when unhappy with a script and having others around him work to maintain his fame, he remarks: “I’m not supposed to be a nice person, I’m a star!”

Alex makes the lives of those around him – generally – a misery. And demonstrates that making television, even a popular show with a character as loved as Eddie, is Not A Nice Business.

The twist comes when Alex, egotistically checking his fan mail, discovers letters stored at the Yorkshire Television post room (still displaying its advertising posters for The Beiderbecke Connection (1988)) addressed to Eddie and asking for help; he is upset and humbled, noting “These people are serious. They’re in trouble […] Some of these people could really use an Eddie Weary.” So, without permission, he dons his costume and takes to the streets of Bradford in the famous clapped-out Datsun, clutching a plea from somebody who needs help in the real world…

Fig. 2: Look, it was even on the cover of the TVTimes! Did you miss that issue? You can get it here.

For me, it’s a very enjoyable show to revisit. I love the flattened vowels of Yorkshire, the dialogue, the performances and the settings – along with the ruminations on the industry where more effort is put into making a piece of entertainment than helping real people in similar situations. It’s also stylish; both film and film-series-within-film are bookended by the moody song Down These Mean Streets, a torch tune in the manner of Maggie Bell’s memorable melodies for Hazell (1978-1980) and Taggart (1985-2010), played against the seedy neon of the Northern urban night.

But the really fascinating thing is all about perspective. Along the way, some people see Alex, some see Eddie. And, even then, the reaction to the same person is very, very different. The press are primarily interested in Alex as a source of titillating tabloid tittle-tattle. Alex’s secretary/cousin Birdie dotes on him and always has done (ever since naming a gerbil after him) because she sees him as vulnerable. The cold-hearted Madge sees Alex as an annoying but profitable colleague to be tolerated.

Mrs Hebdon is delighted when Eddie arrives on her doorstep because she has given up all hope of ever recovering the rings left to her by her mother and then ripped from her fingers by an unfaithful, bullying husband (“Because I knew you would understand…”). Rita, Mrs Hebdon’s daughter, dismisses him as “just a bloody actor” and berates him for “playing games”. While the neighbouring Mrs McDermott proudly invites Alex into her house and transforming him into a status symbol celebrity visitor, her husband continues to watch the televised football oblivious, while her punk daughter Maureen is only interested in whether the actor can introduce her to rock bands or get her a poster of Led Zeppelin.

The young viewer who assumes that Eddie’s car has broken down while he’s on a case and loans him is bike to complete his assignment (“Go get ’em Eddie!”) offers to guard the studio’s vehicle as a role of honour. The philandering husband who initially wants to thump Alex for glimpsing his fornication in a camper van immediately invites the celebrity for a drink. A debt collecting thug about to administer a vicious blow against a stormy skyline suddenly recognises the face “from the telly” and grabs a nearby piece of refuse for Alex to sign “for our kid”. The professional stripper Roxanne is, however, immune to the fictional charms of Eddie, but sees Alex as a means to acquire an Equity card which is otherwise way beyond her skill set.

Ultimately, it is Alex’s real-life celebrity wealth and not Eddie’s fictional people skills that resolve the situation. A horrifically beaten Mrs Hebdon is disappointed when it is the showbiz Alex who visits her on a hospital ward, but when he returns a moment later as Eddie and announces “I’ll get your rings Mrs Hebdon”, patients and medics break into applause. Alex tricks Roxanne into selling the rings back to him; he even, humbly, lets Rita hand the rings back to her mum. And although it is Alex who buys a new bike to replace the one stolen from the young viewer, the grateful recipient calls out “I knew you wouldn’t forget me Eddie!”

And more and more these days, I realise that it’s all the different views of the same thing that allow some very old things in my life to remain fresh and enjoyable. As per a superb essay that I read the other day…

I recently acquired Swinging TV edited by Rodney Marshall – whose dad, Roger, co-created Public Eye and wrote for many shows not dissimilar to The World of Eddie Weary. My main purchasing motivation was a chapter about the relationship between pop music and 1960s action-adventure series written by Issy Flower, whom you may remember was a guest here on the blog a few months back. And she didn’t let me down – some brilliant research in there.

Fig. 3: Order yours now…

Anyroadup, another essay that caught my attention – and not necessarily for good reasons – was Sexual Liberations & Representations of Gender by JZ Ferguson. I was cautious. I didn’t think that the bottom line was necessarily going to be that good. I mean, I’ve spent decades now studying ITC series[1], I know the episodes, I know the characters, I know the formats, and, you know, somehow I know that when it comes to gender representations from this antiquated branding, this isn’t going to go well…

… which just teaches me that I shouldn’t judge in advance. Because what JZ does here is to offer something very different from my expectations. I’m not going to tell you what that is, because I’d far rather that you all had the delight of reading the piece and getting the same level of extraordinary enjoyment and enlightenment that I did from it.

JZ is also stepping well outside the confines of ITC series. This isn’t a piece fuelled by all the usual suspects of The Prisoner (1967-1968), The Saint (1962-1969), The Champions (1968-1969) or even The Avengers (1961-1969). Oh, there’s some rather lovely film rarities surfacing as my eye homes in on the italics that pepper the text as cultural navigation points. What’s this? Somebody who’s bothered to watch Gideon’s Way (1964-1965)! And The Sentimental Agent (1963)! And – blow me – if they haven’t ventured beyond the confines of celluloid escapades onto the more rarefied territories of tape. All of a sudden, I’m seeing references to The Corridor People (1966)! And – goodness – is it, can it be, is that The Fellows (Late of Room 17) (1967)!? How magnificent! Somebody else has actually watched that.

But JZ hasn’t just spooled these discs through the machine in a background boxed-set binge. Drawn from myriad episodes across all these brandings are countless little nuggets of evidence – page after page of examples of different actions and expressions and behaviours. And it’s just dazzling. And I don’t know why I’m being dazzled because, after all, these are the same series that I’ve been watching for years – I know all these actions and expressions and behaviours only too well…

… but it’s the shape that JZ is crafting them into. It is unexpected, it is different, it is original and it is engaging. The components are nothing I didn’t know, but here they’re taken from a different perspective and used to construct an end product that’s probably better than I deserve to have educating and entertaining me. And the words show me a totally different set of perspectives on something that I’ve probably been seeing from the same old angle for the last 40 years or so.

I’d been seeing Alex, and maybe I’d become blind to Eddie.

So, thank you to JZ and also to all those people whose clever words allow me to continue enjoying the things that I’ve enjoyed for so many years by offering me new, thoughtful, positive takes on old stuff.

Andrew Pixley is a retired data developer. For the last 30 years he’s written about almost anything to do with television if people will pay him – and occasionally when they won’t. Oh… and he’s started reading his Naked City (1958-1963) paperbacks, you know, those rare ones that he bought from the Not In Heckmondwike Book Shop at a very reasonable rate. And – ewwwwwwww! – yes, they are novelisations of scripts by Stephen Frances who wrote the hard-boiled ‘Hank Jansen’ thrillers of the 1940s and 1950s aren’t they? Which probably explains why nice Detective Adam Flint thinks and does a lot of not-very-nice-at-all things that he certainly doesn’t do in the television version. Ewwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww!

Footnotes

[1] … and when I say ‘ITC series’ here I’m saying this like saying ‘Hoover’ or ‘Sellotape’ as a branding which is now a handy shorthand description that encompasses sort of 1960s film series in general rather than just shows made and distributed by ITC, so stuff like ABC’s The Avengers (1961-1969) as well, but just didn’t want to have to go to the fag of writing out ‘1960s film shows made and distributed by ITC and stuff like ABC’s The Avengers (1961-1969) as well’. Damn.

Hi there, I’ve been fascinated by The World of Eddie Weary since I sneaked downstairs to watch TV and saw certain, ahem, scenes in it! I never knew what it was, until someone in a forum told me, and I’ve been trying to track it down ever since. I’d love to actually watch the whole show, and I did reach out to ITV archives to see if I could obtain a copy, but the price for it was far beyond what I could afford. Do you happen to have a digital copy of your original recording?