Alongside the important position of Nordic Noir in European crime fiction, it comes as no surprise that Netflix has utilized this subgenre[1] both on the Nordic markets and as part of the streaming service’s transnational ambitions. Through the impressive range of so-called ‘altgenres’ (or Netflix subgenres) associated with Nordic Noir, the Nordic style and brand has claimed a significant position in the overall catalogue of European crime series on the portal. However, it is necessary to not only read the position of Nordic Noir through generic references or Netflix’s own commissions. Netflix’s acquisition, co-production and new branding models also need to be taken into consideration.

There has been some controversy regarding Netflix’s concept of originality as the streaming service has been accused of ‘strutting in borrowed plumes’. For instance, related to the branding of the BBC series Bodyguard (BBC, 2018), Netflix was criticised for blurring “the line between shows it creates and shows it acquires” (Hughes, 2018). Something similar has been debated regarding the American series You (Lifetime/Netflix, 2018-) that was launched as a Netflix Original outside the US (Hipes 2018). Referencing “Netflix Originals”, the institution forcefully exploits the brand name – including the larger red N in the top left corner of the clickable tills in the platform – as a content qualifier of material not commissioned or co-produced solely by Netflix. In this way, the platform interface aggressively distorts the borderline between Netflix’s own titles and titles only acquired as canned sales.

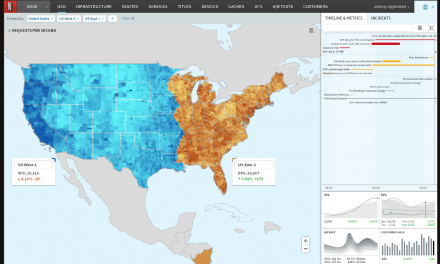

The blurred boundary is also visible in “Nordic Noir” as a Netflix altgenre. For instance, two Finnish crime series, Sorjonen (Bordertown) (YLE, 2016–) and Karppi (Deadwind) (YLE, 2018–), have been actively distributed and branded as Netflix Originals, even if Netflix only acquired them through canned sales (see the red N’s on the tills in the image below). This highlights Netflix’s ‘long tail’ of television content as well as its deliberate blurring of what original content essentially is. As pointed out by Séverine Barthes (2018), there are obvious similarities in the local French Netflix catalogue.

Fig. 1: Bordertown (Grænselandet) and Karppi are branded as Netflix Originals, even though Netflix only bought local distribution rights for the series. This is the case with many Netflix titles available in the Nordic region (image taken from personal interface at Netflix.com).

Local co-production and acquisition of production rights

Picking successful titles from linear broadcasters in order to produce further seasons within the same franchise is an active Netflix strategy too, e.g. the US Nordic Noir reboot of The Killing (AMC/Netflix, 2011-14) or the Spanish series La casa de papel (Money Heist) (Antenna 3/Netflix, 2017-). In such cases, Netflix acquires the rights to continue a series produced for local linear broadcasters, and in doing so they get access to the backlist of previous seasons that may now be branded as Netflix originals. Such a localisation process is part of what Ramon Lobato refers to as “the spatial logics” of Netflix’s TV distribution (Lobato 2019: 54). For Netflix, the first “original” venture was the co-production of the crime-comedy Lilyhammer (TV 2/Netflix, 2012–2014) with the Norwegian public service provider NRK, which clearly shows a prompt interest in the Nordic region as well as the Nordic crime genre at a time when the Nordic Noir brand was on the rise.

Netflix also co-produced the crime serial Kriger (TV 2, Warrior) (2018) with the Danish commercial public service provider TV 2. Netflix’s co-production of Hotel Beau Séjour (Éen, 2017–), a series clearly influenced by Nordic Noir, with the Belgian broadcaster Éen accentuates the international impact of the brand and style. As pointed out by Wayne and Castro (2020), Netflix requires collaboration with local, national television providers to access national audiences. For these broadcasters, an evident motive for engaging with a competitor like Netflix is risk minimising in producing expensive serial content, while the situation also creates an opportunity for Netflix to acquire relatively cheap-priced local content. Today, it is clear that, for Netflix, Nordic Noir crime dramas have – as a recognizable brand – become a safe bet among others in order to claim a regional market position.

Nordic Local Netflix Originals

Nordic Noir’s market value is also noticeable in four recent Nordic serials fully commissioned by Netflix without broadcasters as delegate producers. The Rain (Netflix, 2018–20), the first Danish original production, is marketed as a post-apocalyptic youth drama, but the dimly lit stylisation of the series, the plotline emerging through heavy rain, and Scandinavian forests as prime locations are all identifiable Nordic Noir characteristics. The first Swedish Netflix series Störst av allt (Quicksand) (Netflix, 2019) is also a youth drama, but simultaneously it contains a crime plot and a similar Nordic Noir style. Through the creator Camilla Ahlgren, a celebrated writer within Swedish crime-series production, e.g. The Bridge (SVT/DR, 2011-18), the paratextual branding unswervingly connects Quicksand to Nordic Noir.

The first Norwegian Netflix series, Ragnarok (Netflix, 2020-), is a supernatural youth drama containing a murder story as the primary narrative engine of the drama, created by the Danish writer Adam Price, the creator of several significant Nordic Noir titles including Borgen (DR, 2010-13), which has recently been acquired for continuation by Netflix. The recent Danish series Equinox (Netflix, 2020) also combines a well-paced Nordic Noir-like crime plot with inclinations towards the supernatural. In this way, the four Nordic originals hold many affinities with Nordic Noir, accentuating the influential style as an important market penetrator for Netflix. The mixture of a youth drama and Nordic Noir in two of the dramas clearly indicates a melting-pot for the most popular Nordic genres at the time of commissioning the series, which of course points towards the international success of the Norwegian drama SKAM (NRK, 2015-17) as well as the prolific position of Nordic Noir.

Four different Netflix models

What is a Netflix original, then? Altogether, Netflix employs at least four different strategies to present series as ‘original’ through the platform (Hansen 2020):

- the BODYGUARD model

(branding of exclusive acquisitions as original content)

- the MONEY HEIST model

(acquisition of production rights)

- the LILYHAMMER model

(co-producing content with local players)

- the HOUSE OF CARDS model

(commissioning own “originals”)

Among many other market strategies, Netflix has successfully exploited popular Nordic Noir in ways appropriate for the online strategy and identity of the platform. At the time of writing, Netflix has not applied for public Nordic funding for their dramas, although their production model may comply with the guidelines for both national and regional co-funding. At the same time, co-producing series with Nordic commercial public service providers Netflix, tacitly, complies with the obligations of these institutions. Acquiring the series airing on public service providers, Netflix even establishes and profits from a long tail of Nordic ‘traditional’ and commercial public service material, e.g. the acquisition of the first three seasons of DR’s Borgen makes the public service series accessible only behind a commercial paywall.

In other words, one could claim that Netflix serves a local purpose in continuing and distributing material created by or for local institutions, but in doing so the streaming service may commercialise originally freely available public service content.

Fig. 2: The blurred boundary between commissioned and acquired series is a common practice carried out by most streaming services. This affects perspectives in the press too. In Sarah D. Bunting’s review of the recent Danish series Efterforskningen (The Investigation) (TV 2, 2020), she appears to think that the Nordic crime drama is an HBO series. Motivated by Pilou Asbæk’s central role in the series, she even highlights that “The Investigation brings Game of Thrones‘ Euron Greyjoy actor back to HBO.

Kim Toft Hansen is Associate professor in Nordic media studies at Aalborg University, Denmark. His books include Locating Nordic Noir with Anne Marit Waade, the edited collection European Television Crime Drama with Sue Turnbull and Steven Peacock, and the recent book Production Design with Naja Aggerholm and Jakob Ion Wille. He is co-editor in chief of the academic journal Academic Quarter. He has researched Nordic popular culture for so long that he’s starting to like it.

Footnote

[1] For further analysis of Nordic Noir as a subgenre, style, press reference, brand name and place reference, see Kim Toft Hansen and Anne Marit Waade: Locating Nordic Noir: From Beck to The Bridge (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

The points raised in this blog entry were also made in the article “Nordic Noir from Within and Beyond: Negotiating geopolitical regionalisation through SVoD crime narratives” published in Nordicom Review no. 41, special issue I, 2020. The typology of Netflix originals was also re-purposed in the Horizon 2020-report Researching European transcultural identities: production perspectives. The research presented here has been financed by the research project DETECt – Detecting Transcultural Identity in European Popular Crime Narratives (Horizon 2020, 2018–2021) [Grant agreement number 770151].