Last week I gave my first ever lecture by live online video. Not only was this my debut in a medium that was new to me, but I was also asked to talk about a TV Studies topic I have never taught before, namely the sketch comedy genre. That week’s screening for our new intermedial module, ‘Comedy on Stage and Screen’, chosen by my esteemed colleague and CST board member Simone Knox, was the first episode of Monty Python’s Flying Circus (MPFC, BBC 1969-74). Soon I found that this foray into new territory led in some unexpected directions, back to the Music Hall of the 1880s and the story of my ancestor, comedy star Charles Bignell.

Simone asked me to discuss the concept of genre in my lecture, to demonstrate to our first-year students that genre is more tricky than it might appear. Here I was on safe ground. I was wowed by Jacques Derrida’s ‘The Law of Genre’ essay decades ago and avidly absorbed Steve Neale’s and Rick Altman’s work on film genre, for example. My Media Semiotics and Introduction to Television Studies books have sections on TV genre, with material on the sitcom especially. So, I was off and running with my first few Powerpoint slides.

My next step was to follow Fredric Jameson’s dictum ‘always historicize!’, explaining TV channel identity and what being on BBC2 meant in 1969 when MPFC began. I talked about how the Pythons, revolutionary as they were, drew on a sketch tradition deriving originally from live Music Hall performance. Indeed, Terry Gilliam’s irreverent collages of Victorian photographs (Fig. 1) signal MPFC’s debt to, and reworking of, this tradition. TV sketch comedy adapted live Variety shows into broadcast Light Entertainment, as Richard Dyer explained. Here, I began to get sidetracked by my own family history.

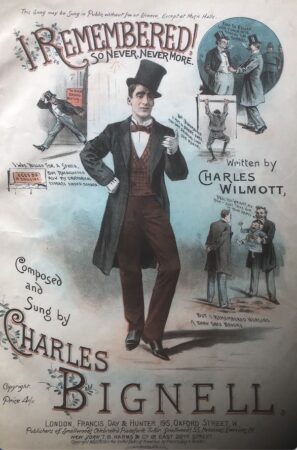

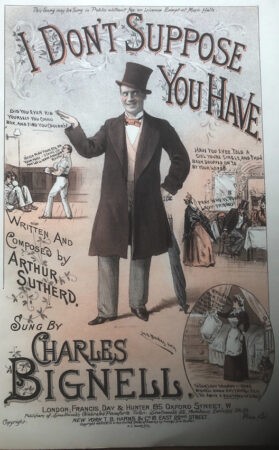

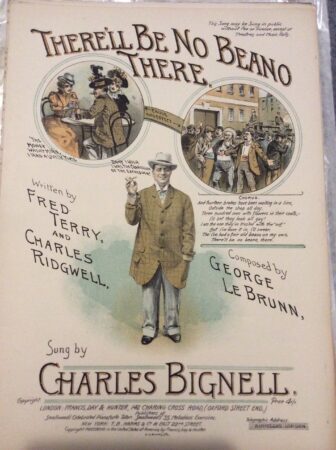

Charles Bignell (1866-1935), apparently my great-grandfather’s cousin, was a successful Music Hall performer. The sheet music of the comic songs for which he was well-known made lovely illustrations for my Powerpoint slides, I thought (Fig. 2). They convey the ribald humour of such performances and their implicit rebelliousness under a cloak of respectability. There is an invitation for audiences to join in with the catch-phrases and choruses, not only while watching the show but also afterwards with friends (by making music at home). They are something like Monty Python’s Lumberjack Song (Fig. 3), for example, undercutting respectability and masculine propriety, and tempting us to join in.

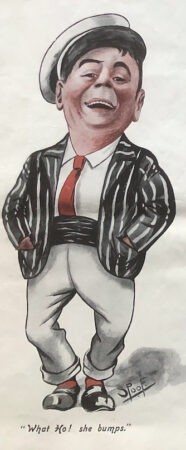

Charles Bignell was known as the King of Fun. He crafted the persona of an aspiring man-about-town who would seize opportunities for pleasure wherever he could find them, but for whom things went wrong when his bravado, attempts at seduction or appetite for alcohol got the better of him. His most well-known song was ‘What Ho! She Bumps’ in which the curious catch-phrase (initially referring to a pleasure-boating trip) rounds off the verses in a string of double-entendres (Fig. 4). In ‘I Don’t Suppose You Have’ he describes a range of comic situations, like being discovered out with a woman who is not his wife or shaping up for a fight to defend his reputation but being ignominiously bested. In ‘There’ll Be No Beano There’ (Fig. 5) he has a great night out with two attractive women but gets so drunk that he cannot follow up the seduction. Decades later, Python refashioned these tropes in sketch dramas that undermine a whole range of potential male role-models and masculine authority figures, from military commanders to sexually confident lotharios, each of whom ends up exposing their inadequacies.

Fig. 4: Cartoon of Charles Bignell performing ‘What Ho! She Bumps’ in The Variety Theatre magazine, 11 August 1905, p. 13.

Charles Bignell’s comic turns relied on dextrous verbal performance, in tongue-twisters and rapid patter of the kind that Python created in The Philosophers’ Song and the extended monologue that concludes The Parrott Sketch. It was a comic form that Ronnie Barker went on to perfect in The Two Ronnies’ Pismonouncers Unanimous sketch, for example. In ‘The Baby’s Name is Kitchener’, Bignell used tongue-twister lyrics to undercut attempted patriotism, and make fun of his wife, by extending a roll-call of names and places from the Boer War to a ridiculous degree:

The war, the war, the blooming war, has turned my wife insane

From Kruger to Majuba she’s got Transvaal on the brain

And when to christen our first child, last Sunday week we tried

The parson said, ‘What’s this child’s name?’ and my old girl replied:

Chorus: The baby’s name is Kitchener, Carrington, Methuen, Kekewich, White

Cronje, Plummer, Powell, Majuba, Gatacre, Warren, Colenso, Kruger

Captown, Mafeking, French, Kimberley, Ladysmith, ‘bobs’

Union Jack and Fighting Mac, Lyddite, Pretoria, Blobbs.

Python members’ role in the 1960s satire boom, in That Was The Week That Was’s commentary on politics and press scandals, for example, worked similarly to lampoon the Profumo scandal and The Frost Report comically challenged consensual support for government policy

Music Hall was a ready-made resource for the new radio medium when BBC launched in 1922, though its much stricter regime of taste and decency excluded material such as Bignell’s more racy songs. On 11 January 1933, he appeared in a live radio relay from the Old Pavoli Music Hall, featuring a lengthy roster of stars including George Robey and Vesta Tilley. But this was a ‘greatest hits’ revue that signalled the end of an era. He died in 1935, so never got the chance to appear on BBC’s new Television Service that began the year after.

Early BBC Television used the Alexandra Palace studios to showcase acts from the Music Hall, such as the comic and singer Kate Carney whose comedy persona was a woman always getting into scrapes, like a female version of Bignell. Complete with a pit orchestra and small studio audience, these shows were relayed live to the few thousand homes around London that had TV sets, and early programmes featured comic routines, acrobats, singers and dancers like those that had appeared on the Variety circuit. Later, in the 1950s when Music Hall had largely died out, it was recreated in The Good Old Days (BBC, 1953-86), for a while the longest running television programme in the world. The sketches, stand-up routines and songs of Music Hall and Variety had been cleaned up for TV’s Sunday Night at the London Palladium, Charlie Drake and The Two Ronnies, and The Good Old Days’ politer, nostalgic simulation of the live shows that had led to them became a fixture in TV prime time.

Using the Leeds City Varieties theatre (Fig. 6), slightly remodelled to accommodate multi-camera taping, The Good Old Days’ performers and audiences took on the costumes and language of the Edwardian period. Contemporary acts like Danny LaRue and Barbara Windsor not only appeared as themselves but some impersonated historic Music Hall stars. However, this was a tamed and sanitised version of Music Hall. Just as the King of Fun, the ribald Charles Bignell of the 1890s, had become wealthy and a teetotaller by 1905, The Good Old Days left behind the rebelliousness and disorder of the tradition it adapted. The TV series suggested a cosier past of sing-alongs and working-class community that EastEnders characters (like Barbara Windsor’s Peggy Mitchell) sometimes nostalgically referenced. Similarly, the Pythons’ edginess has been somewhat blunted now by the ways its legacy became the mainstream, and some of the sketches’ sexism and cultural elitism is out of step with the times.

I finished my lecture with the obligatory list of Key Points, trying to weigh up MPFC and television sketch comedy in general. MPFC is an excellent choice to ground a discussion of comedy and genre, because it parodies a whole panoply of other TV genres. More interestingly, its sketch show form foregrounds the odd juxtapositions thrown up by broadcast flow, channel switching, junction points in the schedule, and the interstitials that link and separate one TV sequence from another. The show debates the question of what television is, or at least what it was by 1969. An important aspect of MPFC’s achievement is meditating on what television borrows from, refashions or invents for itself, and thus how television becomes contemporary by representing versions of its own past, present and possible future. This is not an original insight, but it became newly interesting to me last week because of the continuities and discontinuities that my lecture preparation unexpectedly threw up. One of the joys of television, and also of teaching, is the power they have to forge personal and intimate connections, though those connections might also seem contingent and mostly inconsequential to someone else.

Jonathan Bignell is Professor of Television and Film at the University of Reading. He works on histories of television drama, cinema and children’s media. Some of Jonathan’s work is available free online from his university web page or from his academia.edu page.

Jonathan, this is a great read and to think you have a Music Hall ancestor – truly sensational (as in the Victorian meaning of ‘Sensation’. Of course, i’m old enough to remember the long-running BBC programme The Good Old Days, and i always found it interesting to see how then-contemporary TV stars queued up to be on the show. The Posters of your Music Hall ancestor are marvelous. Thanks once again.

Ken