Having recently returned to work after several weeks off work because of anxiety and clinical depression, it seems appropriate to write about a ‘trending’ topic: mental health, mental illness, its representations in popular media, and how all of these affect staff and students in universities. I am referring here to my own experience working in a UK institution of HE but I’m sure some aspects of the situation apply elsewhere. Others have written here about their experiences as academics with the rhetoric of self-care (Catherine Johnson, Karen Boyle) or almost literally working themselves to death (Kim Akass) and with each passing year health and mental health in particular seems to become a more pressing concern in the university sector.

While campaigns to give mental health services equal funding and equal priority as other health services continue, the reality is that mental health services are overstretched, with patients facing long waiting times before a first appointment for appraisal. University counselling services are notoriously over-burdened and students report waiting times of several months: I expect many colleagues have had similar experiences. The current management fetishisation of the phrase ‘student experience’ in UK universities tends to be applied to consumer-driven metrics, rather than translated into providing much-needed services that might actually improve the student experience. Likewise, increasing pressure on academic staff to improve teaching and research, alongside increased workloads and unrealistic expectations of the time needed to complete tasks, are consistently ignored despite yet more rhetoric about improving staff ‘wellbeing’ and facilitating a healthy work-life balance. For anyone with low levels of self-esteem, being told that they must do more, and do better because their work is being found wanting according to unrealistic targets and inappropriate measures simply reinforces patterns of negativity and makes it all the more difficult to maintain mental health. In both cases, the neo-liberal rhetoric of self-care places the responsibility for health and wellbeing on individuals, without acknowledging the systemic and institutional factors at play.

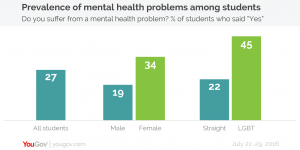

As any academic involved in teaching or pastoral care knows, mental illness is rife among staff and students in universities, with a recent study reporting that one in four students at UK universities have mental health problems. Pressures on counselling services offered to students mean that staff often feel obliged to offer support, despite being unqualified as mental health counsellors and possibly feeling uncertain about the right approach. When a student comes to speak to you in crisis, are you going to turn them away because it’s not your job, or are you going to give them your time and do what you can to help? Most of us would do the latter. But, I find myself thinking, given the stigma still attached to mental illness, how many students are experiencing similar crises and not coming to talk to anyone? And what can we feasibly do to improve this situation?

To me, this is partly about fostering an environment that is open and accepting. I often use these blogs as a place to rant about diversity—or its lack—in television, and in university curricula, and issues of dis/ability and mental health are part of this. When I teach classes on representation in TV, I try hard to be inclusive and draw on examples that depict trans/gender, hetero- and other sexualities, and a range of racial and ethnic identities, partly to engage students who might be disinterested in repeated discussions of how hard it is to be a white privileged male as according to film and television. Likewise, I have recently been working on using film and TV texts that debate, or in some cases, exploit dis/ability, including mental illness.

Homeland is often held up as an example of Islamaphobia, yet its representation of protagonist Carrie Mathison as dealing with bi-polar disorder has been praised for its realism. Empire, while more overtly melodramatic than Homeland, has received positive comments for its open debate about black homosexuality, and two of its main characters also have severe mental health problems: André is bipolar, and Jamal suffers from PTSD after being shot by Freda Gatz. Bipolar disorder is, in one sense, a natural choice for TV series, apparently offering multiple opportunities for drama, conflict and emotional scenes and both Homeland and Empire exploit this. However, both also depict the ways in which sufferers and those who care for them, may refuse to fully accept the consequences, especially long-term consequences, of the illness, seeing it instead as a personal weakness or something to be hidden. In Homeland, for example, Carrie has concealed her condition from her employer, the FBI, while Empire reveals that André’s paternal grandmother also suffered from bi-polar disorder; something her son, Lucious, Andre’s father, kept from his own child. Marvel series Jessica Jones offers a detailed exploration of PTSD through its eponymous sexual abuse survivor protagonist, who seeks to help others, though this makes it hard to watch at times. All of these series have provoked engaged classroom discussion, with many students clearly finding it important that such depictions are ‘done right’.

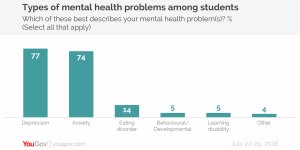

Depression and anxiety—the most common mental health problems among students and the general population—are, however, some of the least depicted.

Soap opera regularly includes characters suffering from depression and related storylines, but the more critically acclaimed and valued drama series tend to avoid it in favour of more dramatic conditions, or use it but don’t name it. Breaking Bad would have been much more interesting to me if Jesse’s depression were unambiguously clinical depression and treated as such by the series. Various mental health organisations and charities have guidelines for responsible representation of mental illness or offer media advisory services because they know how important these kind of representations are.

Media portrayals and reporting of mental illness are incredibly powerful in educating and influencing the public. When done well, the media can be a tremendous tool in raising awareness, challenging attitudes and helping to dispel myths. It can give people with experience of mental health problems a platform and can offer insight for the public into health problems they may have known little about. (Time to Change)

One series I have found particularly successful in allowing students to discuss mental health problems is My Mad Fat Diary (E4, 2013-15), which presents self-harm and eating disorders—two issues especially pertinent to young people—as well as therapy and mental health treatment from the point of view of its 16-year-old protagonist Rae (Sharon Rooney).

Based on the early life of Rae Earl, and published by her in 2007, the series won praise for the way it did not define its main character by her illness, and for its humour, channelled through Rae’s inner thoughts and on-screen annotations. Her strength in dealing with the various parts of her life is emphasised consistently. My Mad Fat Diary may have been significant to standard-age students because it was current when they were teenagers, but it—and the other series mentioned above—allowed them to debate representations of mental illness at a critical distance, without losing sight of how ‘incredibly powerful’ such representations can be. By including series and discussions like these in my TV classes, I aim to demonstrate that mental illness is a valid, and very current, topic of study and debate In addition, all the series’ ability to dispel myths or challenge attitudes can help educate students about mental health as well as about televisual strategies of representation.

Creating a learning environment that is inclusive, that gives minority or less privileged groups of students permission to speak, and that accepts a range of experiences and responses as valid is increasingly important to me. Normalising mental illness is part of this aim, and studies demonstrate that young people and students in marginalised groups have a higher incidence of mental health problems.

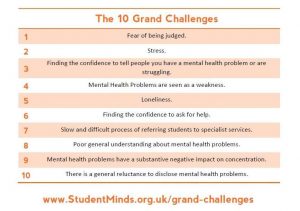

My own experience of mental illness enables me to better understand the student experience of it, in all its forms. This year I took the decision to be open about my anxiety and depression in induction sessions for new students, and in the introductory session of all my modules. In previous years I had made statements to groups of students about how mental illness would be treated no differently to physiological illness in the hope of encouraging any sufferers to come forward and ask for help when necessary, so this was a logical next step. My openness about this is certainly in danger of seeming like over-sharing, but it has made a difference, with some students declaring their depression, anxiety or other mental health problems more easily (and for young adults this is never going to be easy). A few students have told me that they appreciate this normalising of mental illness and that it makes them feel more accepted. Research by Student Minds identified challenges facing student mental health and of the top ten, many are about the stigma attached to having a mental illness, suggesting that changes to the environment may well have positive impact.

Another effect of taking this approach, naturally, is that when students do wish to declare an issue, or need help with managing their studies alongside their illness I have made myself visible. Many of my colleagues would, I’m sure, be equally sympathetic and helpful to students suffering from anxiety or depression, but my openness about my own experience encourages students to approach me with more confidence. (Admittedly gender may also be a factor here: I am the only permanent female member of staff in a team of seven).

I’m not necessarily recommending this as a strategy, nor am I suggesting that this will have a major impact. In an increasingly pressured university environment, however, mental health is an issue that will not go away even though attitudes to it are, slowly, changing. Doing something about it myself and seeing it make a difference, however small, allows me to take pleasure in my job, something I experience less frequently these days. After all, if I’m going to suffer from mental illness, I may as well own it.

Lorna Jowett is a Reader in Television Studies at the University of Northampton and coordinator of the Cult TV: TV Cultures Network. She is the co-author with Stacey Abbott of TV Horror: Investigating The Dark Side of the Small Screen (2013), author of Sex and the Slayer: A Gender Studies Primer for the Buffy Fan (2005) and co-editor of Time on TV. She has published many articles on television, film and popular culture, and her forthcoming book examines gender in the Doctor Who franchise.