There has been something of an auto-ethnographic turn in some quarters of recent television scholarship, with a number of academics reflecting on their engagement with television as viewers and as scholars. In 2008, Karen Lury described her anxiety around her gradual disengagement with television culture, and earlier this year, Christine Geraghty described her reluctance to embrace the digital switchover. This self-reflexive, self-revelatory approach – it is telling that the titles of both of these pieces take the ‘Confessions of a…’form – is one that has been adopted by The Midlands Television Research Group in our ‘Managing Television’ project which took place between the summers of 2010 and 2012.

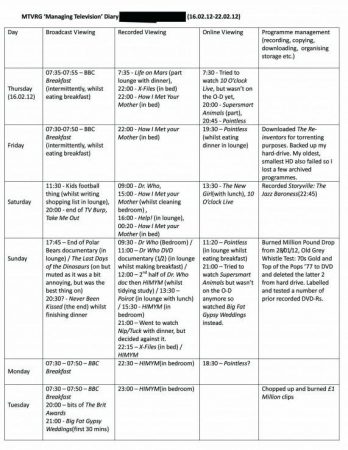

During the summer meeting in 2010, we realised that, in informal post-meeting chats, we were talking as much about how we were watching television as we were about what we were watching. We decided to begin keeping a regular, detailed record of our own personal viewing habits in the hope that such an approach would bring to light trends in our individual and collective viewing. It was quickly realised that as well as including data about what we watched, when we watched it, and how we watched it, we were all spending a great deal of time ‘doing other things with television’ that didn’t actually involve any watching at all: recording programmes onto hard drives, burning them onto DVDs, clearing hard drives, downloading. A viewing diary template was designed to record instances of ‘Broadcast viewing’, ‘Recorded viewing’, ‘Online viewing’ and ‘Programme management’ and data was collected by the entire group over a whole week, three times a year. Keeping and talking about these diaries has formed the basis of the ‘Managing Television’ project.

Particularly discernible in our diary discussions were the tensions and negotiations inherent in accessing and managing ‘television as digital media’ (Bennett and Strange 2011). As a group, we were consistently surprised by just how much of our television activity constituted not watching – either by the television playing away to itself or to children in a corner, or by our doing something with television without actually watching it. It is only in the context of digital choice, and the concomitant malleability of television content, that a distinction between ‘watching’ television and ‘doing something’ (else) with television makes sense. Furthermore, we were struck by the labour intensity of such practices, a phenomenon which we have come to call ‘digital housework’; ‘Managing Television’ thus came to mean ‘coping with television’ as much as it did sorting or controlling television content. By documenting in detail our relationship with television, we were able to see clearly the extent to which it insinuates itself in our lives, and, in addition, how inured we have become to its presence. This is particularly evidenced by the high frequency with which group members accidentally omitted data that ought to have belonged in the ‘Programme Management’ column of the diary. This suggests that much of the ‘work’ that goes into managing television is often invisible and easily forgotten.

Most diaries also exhibit a range of different modes of engagement with television through various platforms. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the younger members of the group tended to be more fully immersed in online viewing culture – whether through on-demand services like the BBC’s iPlayer, or through downloads. Some of Lury’s concerns in 2008 were that the variety of online sites of access offered an engagement with television which is too rarefied and individualised, disconnecting the user with communities of viewers that broadcast television offers (Lury 2008). MTVRG members who engage with television in this way, however, seemed more sanguine about such practice; the ease of access to content compensated for any sense of disconnection. In some cases, this was simply a matter of habit: having grown up without access to broadcast television, one Canadian group member is a well-trained user of digital platforms. In other cases, it is a matter of preference: some simply prefer to access television through a larger screen, and as it is broadcast. There is not a stark generational divide here – all group members watch some broadcast television – but this mode of viewing tends to be reflected in the diaries of older members, particularly when viewing for pleasure rather than for work.

Some respondents described how their television watching was increasingly taking place across multiple sites simultaneously, supporting Helen Piper’s contention that television is becoming increasingly ‘plural, participatory and multiplatform’ (2011: 521). Our group was divided on the merits or otherwise of this kind of double-participation with television. Some group members found distasteful the electronic distractions of what Charlie Brooker has called ‘double-screening’ – the practice of watching television and using a smart-phone or computer (particularly to visit social networking sites) simultaneously. Others were eminently comfortable with the activity, going so far as to suggest that rather than characterising this mode of viewing as ‘distracted’, ‘double screening’ should be seen as promoting an attentive, participatory engagement with television.

Such changes in the way we are able to access television programmes opened up discussion over previously taken-for-granted terms. For example the question recurred of a definition of ‘must-see-TV’ in an age where, to reference the BBC iPlayer’s ubiquitous tagline, television is almost literally un-missable. The broadcast schedule, however, remains a vital part of most members’ relationship with television, and there was a pleasing synchronicity to some of our television appointments. The pleasure we found in having watched the same thing at the same time is accentuated in the age of digital choice. Participation in the Managing Television project also revealed to some of us our lack of engagement with television – broadcast or otherwise. ‘Must-see TV’ to them simply meant ‘I must see some TV’! Many group members were struck by how little time their lives afforded them to have the same meaningful relationship with television they had once enjoyed. This was particularly true for those with young families, whose diaries often display a preponderance of children’s television; television, one suspects, that they were usually not watching themselves.

However, it is perhaps reassuring that similar conclusions were reached in each discussion: despite numerous technological shifts, and the impact that this has had on the means of access to television programmes, and the amount of ‘digital housework’ that we do, our viewing habits are still governed by our social relationships. To quote David Morley: ‘television viewing […] is still largely conducted within, rather than outside of, social relations’ (1986: 14). The diaries demonstrate that TV viewing still ‘contributes to the structuring of the day, punctuating time and family activity – such as meal times, bed times, homework times and so on’ (Ibid 32), with many entries being prefaced or succeeded with statements noting that a particular programme was viewed ‘whilst waiting for’, ‘whilst eating dinner’, ‘background noise for cleaning’, ‘before bed’ and ‘whilst getting ready’.

Inscribed into our diaries – in the programmes we watch, in the ways and locations in which we watch them, even in the gaps between what we watch – are the routines, rhythms and minutiae of our individual daily lives. Our methodology for collecting data about our engagement with television in its various forms has provided us with a fascinating record of our lived experiences of television as a ‘medium in transition’. However, the labour involved in documenting this data in such minute detail eventually took its toll on our results – fatigue had begun to set in – and the project drew to a natural conclusion at the two year mark.

Reflecting periodically on our own television habits has prompted us to think in more detail about the changes in our relationship with our object of study as scholars and as viewers. Through the ‘Managing Television’ project, we have found that the demands that we are able to make of television – to be omnipresent, ever accessible, and to be flexible – are proportional to the demands that television (and television culture) makes of us – to be alert, to stay perpetually current, and perhaps even to go outside of ‘television’ to fully engage with it. Managing Television has allowed the group to register the various changes happening within our own television practices, and thus to engage with questions of the evolving character, meaning and culture of television at large.

Hannah Andrews is a Lecturer in Film and Television Studies at the University of York. Her research has centred on the relationships between film and television as media, cultural forms and industries in Britain, and on television institutions (particularly Channel 4 and the BBC). She has published in Journal of British Cinema and Television, Screen and Visual Culture in Britain. She has been a member of the Midlands Television Research Group since 2008.

Richard Wallace is an Associate Fellow in the Department of Film and Television Studies at the University of Warwick. He is currently conducting archival research on the television engineer and freelance photographer John Cura, as well as working as a research assistant on a project investigating the current transformation to digital projection in British cinemas. His PhD was on the comic mockumentary in film and television and he has published articles on Dr. Who and Ernst Lubitsch’s film style. He has been a member of the Midlands Television Research Group since 2009.

The Midlands Television Research Group (MTVRG) meets three times a year and is a forum for television academics in the Midlands to discuss television programmes, recent television scholarship and its pedagogicial applications, and to undertake group research projects. The members of The Midlands Television Group involved in this project are: Hazel Collie, Helen Wood (De Montfort University), Ann Gray (University of Lincoln), Paul Long (Birmingham City University), Hannah Andrews (University of York), Charlotte Brunsdon, Gregory Frame, Mary Irwin, Rachel Moseley, Joseph Oldham, Karl Schoonover, E. Charlotte Stevens, Lauren Thompson, Richard Wallace, Helen Wheatley (University of Warwick).